Haves and Have-Nots: The Borders Between School Districts Often Mark Extreme Economic Segregation. A New Report Outlines America’s 50 Worst Cases

This is the latest in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing education into focus through new research and data. See our full series.

The Rust Belt city of Rochester in western New York has the most economically segregating school district border in the country, walling off the high-poverty education system from its affluent neighbors next door, a new report has found.

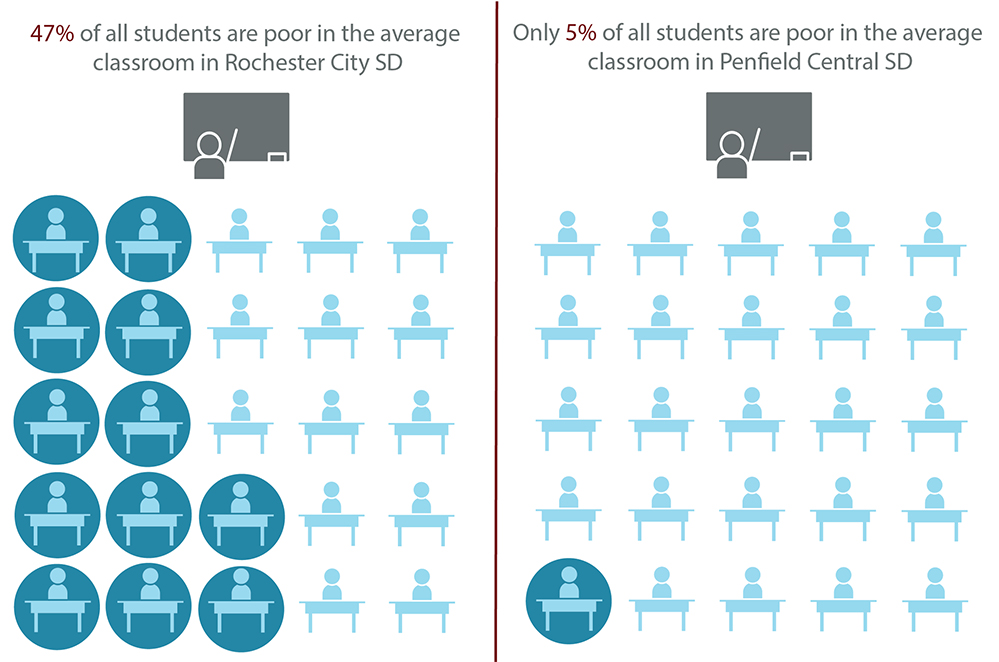

About half the children in Rochester live in poverty, and many of them struggle to get adequate food, health care and housing, according to the report, released Wednesday by the nonprofit EdBuild. In Penfield, a Rochester suburb, the student poverty rate hovers in the single digits, and children fare much better.

“It is a steep challenge for the Rochester schools to serve such a large proportion of these high-needs students,” according to the report. “But Penfield, just next door, has a student poverty rate that mirrors the tony ski town of Aspen, Colorado.”

The report highlights America’s 50 most segregating school district borders, which researchers say divide communities into haves and have-nots. In the EdBuild analysis, the nation’s most segregated school district borders cluster in the Deep South and along the Rust Belt in the North. On average, poverty rates among school-age children are 30 percentage points higher in school districts on the wrong side of the border. Meanwhile, the average annual household income between impoverished districts and their more affluent next-door neighbors differs by $43,000.

The concentration of poverty in Rocheseter is “a systemic crisis,” said Rev. Lynette Sparks, the acting head of staff at the Third Presbyterian Church in Rochester. Sparks is a founding member of Great Schools for All, a local nonprofit that promotes voluntary integration between Rochester and its suburban school districts. In Rochester, she said, “It’s as if you’ve got 100-foot brick walls between every single district that these kids can’t leap over.”

In communities across the country, school district funding is largely dependent on local property taxes, incentivizing communities to maintain narrow school district borders that uphold economic segregation. In fact, the issue is generally worse in states where school district lines are drawn around individual towns, said Zahava Stadler, EdBuild’s policy director. As a result, a school system can find itself in a tough spot if the community’s local economy falters. Theoretically, the district borders “could be redrawn in ways that diminish segregation if somebody were to take up that mantle,” Stadler said.

Though the report focuses on economic segregation, it also observed racial disparities in many districts. On average, white student enrollment is 55 percentage points higher in the affluent school systems. Just 10 percent of students in Rochester are white, compared with 84 percent in Penfield.

EdBuild previously released a similar report based on student poverty data from 2014, as communities across the country were still feeling the lingering effects of the recent recession. Although much of the country has rebounded and the national student poverty rate has declined a few percentage points, many communities remain strapped by downturns in their local economies. The earlier report found that the school district border separating Detroit from Grosse Pointe in Michigan was the nation’s most segregating, but districts at the top of EdBuild’s lists both years generally fell within a few percentage points of one another.

The new report measures economic segregation along school district borders by comparing child poverty rates in 2017 between neighboring cities. Communities that struggled prior to the recession remain in trouble today, researchers found.

Such a situation continues to play out in Rochester, where efforts to promote education equity between the city and its suburban neighbors have floundered. In fact, Rochester is “a poster child for isolation,” Stadler said, sharing borders with five school districts that EdBuild ranks in the nation’s top 50 most economically segregating.

“Rochester is surrounded by better-off districts,” Stadler said. “Every single one of its neighbors has a lower poverty rate than it does. To say, ‘There’s nothing that can be done,’ is patently false. There are resources in the area that could be tapped for Rochester’s schools if we just thought differently about how those school districts should be organized.”

‘Poster child’

In Rochester, residents have been grappling with segregated school district lines for about a century. In 1929, officials proposed a countywide school district in the area, but suburban residents rejected the proposal, and school district lines that match city limits remain intact today.

As black residents flocked to Rochester in the 1950s and ’60s for jobs at industrial giants like Kodak and Xerox, officials in neighboring Penfield took steps to shelter its affluence. White residents fled to the suburbs and Penfield adopted “exclusionary zoning” rules to limit development to single-family homes and opposed more affordable housing options, according to the report.

In Warth v. Seldin, a case that came before the Supreme Court in 1975, low-income Rochester residents lost their battle against Penfield’s exclusionary zoning practices. The court ruled that the Rochester residents lacked standing to sue, even if Penfield’s housing policies effectively gated it off from low-income residents.

“Our school finance system, with its heavy reliance on local property taxes, gives every wealthy community an incentive to do what Penfield did,” according to the report. “First, turn down proposals for a wider, more inclusive school district and then, keep the walls up, property values high, local dollars in, and needy kids out.”

Similar to many cities in the Rust Belt, industrial jobs in Rochester dried up and economic hardship ensued.

Despite the division between Rochester’s schools and those in the suburbs, there are efforts underway to close the gap. Under an urban-suburban student transfer program, students of color from Rochester can voluntarily transfer to participating suburban districts. But an initiative to attract suburban students to Rochester schools, funded through a $1.2 million state grant, was deemed by many to be a failure. Under the program, just 10 suburban preschoolers attended class at a Rochester campus.

For decades, officials in the community have scoffed at the idea of combining the Rochester school district with its suburban neighbors. There’s a perception among some parents that their children will underperform if they attend the city’s struggling schools, Sparks said. But because of concentrated poverty, the city can’t address the issue on its own. That’s why a broader community effort, which encompasses the city and its suburbs, is vital, she said. But “when push comes to shove,” she added, parents tend to focus narrowly on their own children rather than on community improvement.

“They’ve never treated it like a community problem,” she said, but “the truth is, we all bear responsibility.”

While 60 percent of Rochester residents support a countywide school district, just 49 percent of suburban residents agree, according to a 2018 survey by the Democrat and Chronicle newspaper.

“People are, in a sense, trapped in a mindset that however their school district is drawn is the way that school districts work,” Stadler said. But with political courage, she said, state lawmakers could redraw school district borders in a way that promotes economic and racial integration.

The fault lines

Beyond Rochester, EdBuild researchers found that the problem is largely concentrated in a few states. New York, for example, is home to nine of the country’s 50 most economically segregating school district borders.

But the worst state offender, according to EdBuild, is Ohio, home to 17 of the country’s most egregious borders. Communities in that state share similarities with Rochester: As the economies in metropolitan areas faltered, school district borders “served to quarantine their misfortune” and allowed neighboring suburban districts to escape the economic fallout.

Youngstown, once a prominent steel town, shares the nation’s second- and third-most segregating borders with neighboring communities Canfield and Poland. While 47 percent of Youngstown children live in poverty, just 6 percent of those in Canfield and 7 percent in Poland have similar economic realities.

“There are a few states that might take a hint from the fact that their districts appear repeatedly,” Stadler said. “Ohio always lights up like a Christmas tree when you look at the problems created by school district borders.”

Outside the Rust Belt, EdBuild found a cluster of segregated borders along the Deep South’s “black belt,” a region originally named for the rural area’s dark, fertile farmland. A district line separating the Claiborne County School District in Mississippi from those in Hinds County is the south’s most segregating, researchers found.

To politicians interested in improving conditions, EdBuild researchers point to several anecdotal successes. In Vermont, for example, schools are funded through a state property tax and, as such, local property values don’t define the level of funding school districts receive. And in North Carolina, school districts are drawn at the county level. School districts that are geographically larger, EdBuild found, are generally less segregated. Such decisions are in the hands of state lawmakers who draw school district borders.

“The educational outlook for the children trapped behind arbitrary borders — just a few feet away from much better opportunity — is not dependent on local economies,” according to the report. “Rather, their future is dependent on political bravery.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter