From Tragedy to Triumph to Failure: How 9/11 Helped Pass No Child Left Behind — And Fueled its Eventual Demise

By Kevin Mahnken | September 8, 2021

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Frank Brogan was a man nearing the pinnacle of his political life. A former teacher, administrator, and commissioner of schools in Florida, he’d been elected lieutenant governor of that state in 1998 running alongside Republican Jeb Bush. Now he was welcoming the governor’s brother, President George W. Bush, to Sarasota’s Emma E. Booker Elementary School, where he planned to meet with a group of second-graders and deliver a speech pushing for action on the stalled No Child Left Behind Act.

The bill, perhaps the centerpiece of Bush’s “compassionate conservative” agenda, had sprinted through the U.S. House and Senate before hitting the summer quagmire that so often ensnares federal legislation. Administration officials hoped that a presidential swing through Florida might reawaken Washington and speed its way to passage.

It was only minutes before the activities began when Bush learned that a plane had collided with one of the World Trade Center towers. Like many, Brogan initially assumed the reports referred to a light aircraft that had wandered off-course.

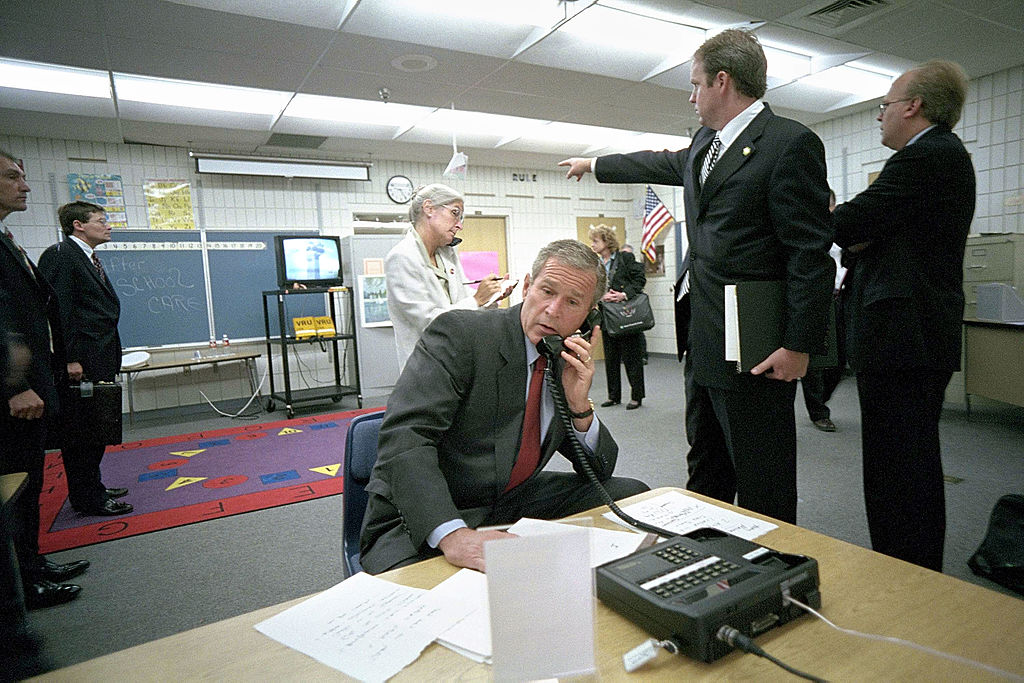

But as the room filled with the singsong cadence of kids reading aloud — the activity, centered on a phonics-heavy story called The Pet Goat, had been selected to draw attention to NCLB’s literacy provisions — the atmosphere changed noticeably. White House Chief of Staff Andrew Card approached Bush to whisper the news of the second crash. And over a seven-minute interval that would be picked apart for years, the president’s focus seemed to drift between the children in front of him and the horrors unfolding in Manhattan. Brogan called the moment “extraordinary.”

“He didn’t change his expression, but the color in his face visibly changed, especially for people who were only a few feet from him. It was crystal-clear that whatever he just heard was very disturbing.”

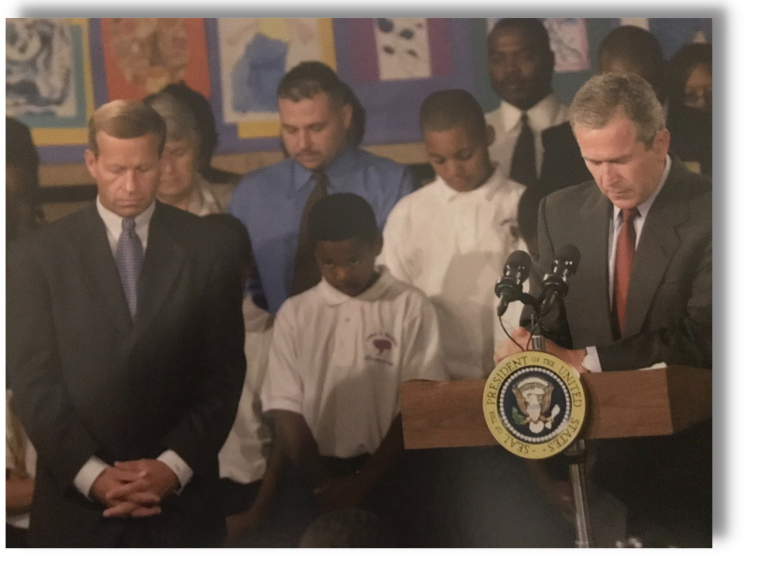

As the activity wound down, the president excused himself to join a call with national security leaders. After stopping to deliver brief remarks from the school’s media center, including a moment of silence for the still-uncounted victims, Bush’s entourage headed immediately to Air Force One. The advocacy tour was over. A wartime presidency had begun.

The ties linking 9/11 with NCLB were the result of a historical accident. During the 20 years that passed since that day, the U.S. government undertook generational commitments to both rid the world of fundamentalist Islamic terrorism and provide an excellent education to every American child. Begun amid a swell of bipartisan approval, both missions fell far short of their goals as the afterglow of national unity first ebbed, then extinguished altogether. And while much of the vision of NCLB is preserved in federal law, controversial requirements around school accountability have been significantly loosened; some of the law’s original architects even attribute its demise, in substantial part, to a combination of hyperpartisanship and neglect that arose as the Bush administration turned its focus to the ever-expanding War on Terror.

“This is really what 9/11 meant: People moved on to other things,” said Sandy Kress, an education advisor to President Bush who helped lead the White House’s efforts to lobby for NCLB. “Afghanistan and Al Qaeda, plus the return of normal politics, that was huge. The president certainly moved on, and so did the rest of the world.”

Moving at ‘breakneck speed — for Washington’

Kress came to Washington after the 2000 election to transform the sweeping education proposals of then-Gov. Bush’s campaign into legislation. He spent years before that as a power player in Texas politics, serving as president of the Dallas school board before receiving appointments to a series of commissions empaneled throughout the 1990s to improve the state’s schools.

At that time, Washington’s role in K-12 schools offered barely a hint of what it would later become. The principal statute governing federal interventions in education, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, had been reauthorized in 1994 as the Improving America’s Schools Act, a fairly radical revision that required states to make “adequate yearly progress” toward proficiency for all their students. But reforms were still driven overwhelmingly by a set of ambitious governors: like Roy Roemer of Colorado, Jim Hunt of North Carolina and Bush of Texas.

By the time ESEA was due for another reauthorization, leaders in both parties were settling on a single model of reform. States would set high standards, deliver the instruction necessary to help students meet them, and institute regular assessments to keep an eye on their progress.

“I think people at the federal level realized they couldn’t get away any longer with simply saying, ‘America’s children aren’t learning enough, but just keep doing what you’re doing,’” said Brogan, who was elected as Florida’s commissioner of schools in 1994 and would go on to lead the state university systems of both Florida and Pennsylvania before serving as assistant secretary of education under president Donald Trump. “We had to come up with some new ideas…and at least spell out with clarity what kinds of things children were expected to master with each of the passing grade levels.”

That bipartisan convergence was reflected in the heavy emphasis placed on education reform by the campaigns of both Bush and Democrat Al Gore during the 2000 presidential election, argued Tom Loveless, former director of the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center on Education Policy. Bush, whose own package of reforms in Texas had won the admiration of even some Democrats in Congress — including California Rep. George Miller, an avowed liberal serving on the House Education and Workforce Committee — was only too happy to break with prevailing orthodoxy in order to build his brand as a different kind of Republican. That included moving away from the party’s oft-stated commitment to abolish the federal Department of Education.

“Bush simply jettisoned that,” Loveless said. “He dropped it completely — it was in the ’96 platform, but it was not in the 2000 platform because the Bush people wouldn’t allow it in.”

“That whole sweet thing that was put together in the ‘80s and came together in various states and then saw this incredible peak in Washington in 2001 — all of that largely fell apart because of 9/11, and the failure of everyone on all sides to hold it together in the wake of 9/11.”

—Sandy Kress, education advisor to former President George W. Bush.

Bush began setting a course for a major new education law almost as soon as the Supreme Court handed him the presidency, meeting at the White House in January with Miller, Sen. Ted Kennedy, and future Republican House Speaker John Boehner. No Child Left Behind, as the proposal soon became known, passed through both chambers even though it was loaded with tough language on equity and accountability. Under the new law, states would be required to test all students between grades 3-8, separate the data by class and ethnicity, and publish detailed school report cards based on the results. Billions of dollars in new federal funding would be allocated to support improvement efforts.

Margaret Spellings — a senior Bush advisor whom he would later appoint as U.S. secretary of education — said she didn’t fully appreciate at the time how quickly the initiative came together.

“I was a relative newcomer [to national politics], and little did I know that this was all happening at breakneck speed for Washington,” she said. “Particularly when we fast-forward 20 years, it really is amazing that this mammoth piece of policy, the major elements of which stand to this day, got done that fast.”

But the process stalled in conference, a lengthy process intended to iron out the differences between House and Senate versions. As the summer dragged on, dozens of conferees worked through a torturous debate over how to define adequate yearly progress, then left Washington for August recess. The economy was in recession, and the president’s approval ratings were ticking downward. Eager to return permanently to Texas, Kress began to worry how long his sojourn in the capital would last.

“By the end of the summer, things were not so rosy,” he recalled. “We were thinking about trying to rev it up and get going again, and that’s how that Florida trip was planned.”

Reinvigorating bipartisanship

At around 8:15 a.m. on September 11, Kress was in the president’s suite at Sarasota’s Colony Beach and Tennis resort, presenting him with talking points and a visual aid — a chart showing America’s education expenditures growing over time, plotted against stagnant national test scores — for what he hoped would be a news-making speech at Booker Elementary.

On campus, Kress skipped the classroom visit to brief reporters before the president took the stage. Instead, he watched with them as a television at the school’s media center broadcast live footage of United Airlines Flight 175 slamming into the World Trade Center’s South Tower. As the Secret Service moved hurriedly to coordinate the group’s departure, the stagecraft morphed from political salesmanship to an emergency speech.

“Now we’re getting instructions: ‘You are to come with me and stand right here, and the president’s going to give some remarks. First thing, take down the chart’ — I did that — ‘and then stand right here. And when the president says his last words, he will go, and you’ll be right on him, and you’re to get in the car.’ It was all solemn and lockstep.”

From the Sarasota airport, Air Force One sped to Louisiana’s Barksdale Air Force Base (“The plane took off faster than I’d ever lifted off on a plane, and got higher than I’d ever been on a plane,” Kress noted.) There it shed most of its passengers while Bush, still considered a potential target, delivered a statement before departing to another location with his key political and security staffers. With virtually every airplane in the country grounded, Kress and his companions only arrived back in Washington that evening, in time to see the smoking wreckage of the Pentagon attack.

Along with his fears for the country, and intermittently his own safety, he couldn’t help worrying about the fate of the historic law he’d spent most of the year negotiating. Would the massive loss of life, to say nothing of the inevitable military action that would follow, leave room for a huge, expensive law overhauling K-12 schools?

As it turned out, he would later reflect, the collective outrage provoked by the attacks proved vastly more effective at pushing NCLB to the finish line than any messaging event could have. Congress would soon be occupied with authorizing the use of force in Afghanistan and drafting the USA Patriot Act, but both Democrats and Republicans also sought the chance to pass a major piece of domestic legislation and show that the nation’s business was still underway.

“9/11 probably reinvigorates bipartisanship for a bit,” said Andrew Rudalevige, a political scientist at Bowdoin College who has written extensively on the politics of NCLB. “And there was an idea that we have to show, as a country, that we can make progress on things other than terrorism and war: ‘This is something we’ve already gotten most of the way through, and we should do it.’”

Before the year was out, overwhelming majorities in both the House and Senate voted to accept the version of the bill that emerged from the conference committee. On January 8, 2002, Bush signed it, flanked by its congressional stewards, at an Ohio school located in Boehner’s district. The group then proceeded to Kennedy’s home state of Massachusetts for a celebration at the famed exam school Boston Latin. Only time constraints prevented them from flying to Miller’s California stomping grounds, Kress said.

In retrospect, No Child Left Behind was likely too far down the tracks to be derailed by events. But, as Spellings argued, the rush of purpose and unity following 9/11 put “a rocket booster” under it; moreover, national attention was significantly diverted from the last months of negotiations, which may have made final concessions go down smoother.

“They were trying to hold that coalition together without offending the far left or far right,” Loveless said — a towering task, given that teachers disliked the new testing requirements and conservatives resented losing out on a longed-for federal voucher program. “Bush really wanted a bipartisan bill, and I think the focus on foreign policy allowed them to do whatever they needed to do in conference and get the bill out.”

A short honeymoon

American flags were still flying from windows, and the renewed sense of national assurance only beginning to waver, when skepticism of NCLB began festering in school districts and state capitals.

Conflict arose almost immediately over new money. Under the law, total federal funding for K-12 schools increased by nearly 60 percent between 2000 and 2003. But for schools now awakening to the threat of sanctions (including governance changes like the mass replacement of staff or restructuring as a charter school) if their students didn’t make consistent, measurable strides toward college readiness, it seemed unfair that escalating expectations on their staffs weren’t accompanied by continuing commitments of resources.

Their doubts spread soon enough to the public at large. In a 2006 paper written at Brookings, Loveless noted that surveys from the law’s early years demonstrated little widespread understanding of its impact, including penalties for consistently underperforming schools. But as participants learned more of NCLB’s key provisions, they consistently came to like it less, he found.

“I think one thing NCLB was able to paper over was the fact that it did have punitive measures involved,” Loveless argued. “When people were polled on the question, in 2001 or 2002, ‘What do you do with a failing school?,’ respondents overwhelmingly supported giving more resources to that school — not closing it or transferring teachers or anything like that.”

Combined with its “utopianism” — the law put forward the aspiration that every student in the country would reach proficiency in math and reading by 2014, a starry-eyed notion that later became a punchline — NCLB’s main weakness lay in its fundamental challenge to Americans’ sunny perceptions of schools, Loveless said.

“It’s been a mainstay in polling: People are just happy with their local schools. And parents are even happier with the schools they send their own children to. So once it became evident that those schools were also endangered by sanctions and maybe weren’t quite what they were cracked up to be, [the law] lost some popularity.”

Eventually the dissatisfaction spread to Washington, where even NCLB’s supporters were increasingly bogged down in the fervid debate over whether Bush’s “Global War on Terror” should extend to Iraq. Along with industry groups like the Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable, a diverse alliance of civil rights organizations including EdTrust, La Raza, and the Urban League had pushed hard to make testing and accountability a reality in every American school; but by 2004, NAACP chairman Julian Bond accused its mandates of fostering a “drill-and-kill curriculum.”

Consistent blows were landed by none other than Kennedy, a figure as vital to NCLB’s passage as any except the president. On the second anniversary of the happy ceremony held at Boston Latin, Kennedy’s office issued a press release giving Bush a “D-minus” for rolling out his signature education reform. In an unmistakable dig at Bush’s famous photo op of the previous year, the release called it “way too soon for the ‘Mission Accomplished’ banner on No Child Left Behind.”

For the temporary boost it delivered to American pride and purpose, Kress said, September 11 ultimately sabotaged the “nice, short-term story” of NCLB’s enactment.

“Passing a bill should be a very positive event in a movement, but if you think passing a bill is the culmination of a movement, then you don’t understand politics,” he said. “That whole sweet thing that was put together in the ‘80s and came together in various states and then saw this incredible peak in Washington in 2001 — all of that largely fell apart because of 9/11, and the failure of everyone on all sides to hold it together in the wake of 9/11.”

Though NCLB’s authors intended for the law to be reauthorized by 2007, it remained in effect for another eight years as controversy built up over its demands on states and school districts. Researchers have credited the landmark legislation with lifting student achievement and closing achievement gaps in some states, but it has also been blamed for narrowing the curriculum through an over-reliance on testing.

Those concerns contributed to the push to replace NCLB with the Every Student Succeeds Act, which offered states more latitude to design their own systems for measuring school performance. In the years since its 2015 passage, committed reformers have complained that the new law is far too slack, allowing states to potentially ignore failing schools and roll back the assessments that reveal which students are falling behind.

Spellings credited NCLB’s supporters in Congress, industry, and the civil rights world with ensuring that many of its key principles remained in place. But she also warned that a political retreat from testing and accountability was underway, “flying under the banner of COVID and mental health and all other manner of bullshit.”

“The secret sauce — and this is what’s under threat in the states — is annual assessments, disaggregated data, and transparency,” she said. “It’s at risk.”

Rudalevige’s research as a political scientist ultimately led him to study the growing powers of the “imperial presidency.” He agreed that it became increasingly challenging for politicians to mend or improve NCLB — still less reauthorize it — once debates over the War on Terror came to “distract attention and dissolve whatever bipartisanship was still left.“.

“Could you do it if you had full presidential attention? Maybe, but Bush didn’t have that, and he didn’t have the institutional resources to make it work without that. It wasn’t the kind of thing you could put on auto-pilot.”

Lead Image: President George W. Bush was reading with a group of Florida second-graders when his chief of staff, Andrew Card, delivered the news that a second plane had hit the World Trade Center. (Paul Richards and George W. Bush Presidential Library/Getty Images) Photo illustration by Meghan Gallagher/The 74

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter