The Pride of 2009 From Rural North Carolina Reflect on How Their Lives Were Changed by the Chance to Go to College

This is an excerpt from the new Richard Whitmire book The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. See more excerpts, profiles, commentaries, videos and additional data behind the book at The74Million.org/Breakthrough.

The scene: A common room at an Arlington apartment building with a view of Washington, D.C. A Southern-themed buffet from Red Clay & Pigs for a small gathering of the KIPP Gaston Class of 2009: shrimp and grits, chicken and waffles, deviled eggs with bacon, slow-cooked spicy green beans, sweet tea.

The mission: These are alumni who volunteered to start initial planning for next year’s 10th anniversary. Given that this is KIPP Gaston’s founding class, the class that later classes have looked up to since they entered KIPP as fifth-graders, there’s a special weight around getting this right. Having the reunion means something more than a mere party. (I wanted to listen to this group’s reunion brainstorming, so I agreed to provide food and drinks.)

The attendees: The key organizer is Ashley Copeland, a Duke graduate who works in Washington for Morgan Stanley as a social media adviser (and occasionally waitresses at Founding Farmers, an upscale D.C. restaurant). Also there was Chevon Boone, a University of Pennsylvania graduate, who just left her job as a middle school teacher for KIPP D.C. to join Relay Graduate School of Education in Washington to become a teacher of teachers; Myles Nicholson, a Morehouse College graduate, who works as a data engineer for a company in Baltimore; Jasmine Gee, a graduate of North Carolina A&T State University, who lives in Greensboro and works as a quality engineer for a medical device maker; Devin Robinson, also a graduate of North Carolina A&T State University, who oversees logistics for a health care provider; Sylvia Powell, a graduate of Wake Forest University, who teaches for KIPP at its Halifax, North Carolina, school; Monique Turner, another Wake Forest graduate, who also teaches at the KIPP Halifax school; and Joshua Edwards, a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who teaches math to high schoolers at KIPP Gaston.

Being black, and growing up in a place like Gaston, it takes more than KIPP guiding you into college to even out life’s inequities that revolve around race, income, family wealth, social capital, and having the right connections.

The moment: Most gathered here are first-generation college-goers, and their stories are complicated. Going to college wasn’t something most of their families even dreamed about, until KIPP came into their lives, and made that the goal. Today, however, what KIPP did for them is, at times and for some, an uncomfortable discussion, a moment that calls for introspection. Who doesn’t want to believe they would have made it in life on their own, without outside help? And the fact that the KIPP founders are white and they are black adds another level of mostly unspoken awkwardness. Some are blunt, saying they can’t imagine what their prospects would have been had their parents not enrolled them in KIPP. Others are more modestly grateful. Two alumni, however, told me they would have made it this far regardless of KIPP. To what extent the Class of 2009 “owes” its successes to KIPP is a sensitive issue on all sides, with KIPP leaders extremely wary of the “white savior” image.

Furthermore, few believe their lives and careers are perfect. Far from it. Being black, and growing up in a place like Gaston, it takes more than KIPP guiding you into college to even out life’s inequities that revolve around race, income, family wealth, social capital, and having the right connections. That’s something that KIPP is aware of and works on. Regardless of all that, there’s an acknowledgment, given the reality of what happens to poor African-American students from traditional public schools in that area of North Carolina, that they have “made it.” And the scene here, this festive gathering of professionals in a classy party room overlooking Washington, D.C., seems to confirm it.

The discussion: It starts out as small talk, ranging from high school jokes and grudges to inquiries about careers, such as writing software. When the conversation turns to the 10-year reunion, everything gets focused and serious. What about a class gift? Scholarships? Could the Class of 2009 raise enough money to create meaningful scholarships? What about offering career-and-college mentoring to the Class of 2019? That’s something they could do that wouldn’t cost much. What about throwing a serious party, maybe getting a member of the board of directors to lend out their house on Lake Gaston? Who would cater it? Would it be possible to land sponsors for their class? Early into that discussion I depart, removing myself as an outside intruder. Later, Ashley Copeland says they concluded the planning by agreeing to produce a spreadsheet laying out their initial plans that would be shared with the entire Class of 2009.

A school where sharecroppers’ cabins once stood

Recruiting the Pride of 2009 was a leap of faith, on the part of everyone — parents, students, and the two founders. Tammi Sutton and Caleb Dolan had never run a school, and when they were recruiting in rural North Carolina, there was no actual school they could point to. When one finally appeared, it was nothing more than four modular units bolted together. To make it look a little more appealing, they splurged on a brick facade. “Otherwise, people would not have believed it was a real school,” said Dolan. They cheaped out on the delivery of the freezer for the school cafeteria, so when the 500-pound unit arrived, they had to unload it themselves. Dolan, his father, and two helpers wrestled it off the truck and into the kitchen. The finishing touch: some grass they tried to grow in front of the school in the red clay that was once a peanut field.

If they were going to make their mark, it was going to be through relentless teaching and successful learning, not through pretty buildings. So at the end of the year, when the first test scores arrived, it was a big moment. Most of these kids, then fifth-graders, had never passed the state test while in their district schools. Would the leap of faith pay off? “I remember going through the kids’ scores, which were just numbers, but they were representative of so much hard work,” said Sutton. “The fact the scores were above 90 percent in reading and math almost seemed like an anomaly. That just didn’t happen. We were like, ‘Oh my gosh, oh my gosh, how are we going to tell everyone?’ It was a Friday, around 5:30 or 6 p.m., and the kids didn’t come back until Monday. So we just got into the car. And it’s like crazy, but we first went to our board chair’s house. He had a daughter in our first class. Then we just started driving to all our kids’ houses. We showed them the score and say, ‘Can you believe this? Here’s the tremendous growth you made.’”

Soon, it became apparent to both Sutton and Dolan that something more than just good test scores was at stake. “It was really just proving what was possible and wanting to tell families who had believed in this idea, and the kids, that look, this is real. We hadn’t just been saying things that weren’t true,” said Sutton, referring to the promises made to the community.

That was 2002. Much more awaited the Class of 2009. What every student I interviewed cited as KIPP’s biggest influence were the class trips that took them out of Gaston and opened their eyes to the world beyond. Dolan’s most prominent memory about this class was the trips they took, to Washington, D.C., Boston, and New York. For many of their students, this was discovering a new world. Especially memorable, he said, was the Boston trip, where they visited Harvard University. The day the KIPP seventh-graders walked through the Common happened to be the same day as the Boston Pride parade. Although KIPP Gaston took pride in its social justice focus, homosexuality had never been broached.

“Unconsciously, we had been avoiding some conversations that might be at odds with our families’ and community’s values,” said Dolan, referring to the conservative social values, heavily influenced by religion, found in Gaston at that time. Dolan and Sutton had a choice: duck the parade or launch into the issue. They chose the latter. “It would have been easy to just keeping walking and tell the kids that we had to get somewhere. But instead the decision was, let’s sit and talk and have this conversation. Dolan recalls telling the students, “You can’t be just for some people’s rights and some people’s liberties.” Dolan’s memory: “Our students rose to the occasion.”

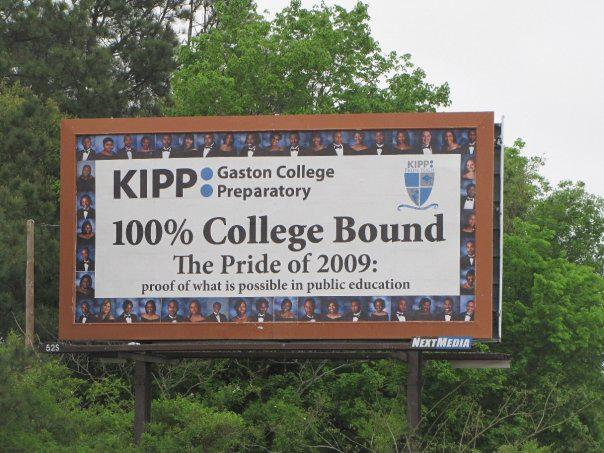

Dolan’s next most prominent memory: the school’s first college signing day, in part because his wife agreed to move to Gaston to be the founding college counselor. “I guess I somewhat owe the Class of 2009 for my marriage.” By that year, KIPP Gaston had nearly 800 students in grades 5-12, including its first-ever senior class. Still, however, everything operated pretty much on faith. Would Dolan and Sutton be able to deliver on their promise of college acceptances? Would it all work out? And then the acceptances started rolling in, including to universities such as Duke, Penn, and Chapel Hill. “Those students became like rock stars to the middle school kids. We had them go watch signing day, and it was like they were watching superstars … We took the middle school kids back to their classrooms and immediately they started writing about what they wanted their signing day to look like.

(At KIPP Gaston, each graduating senior gets one minute to do what they want to announce the college they chose, a skit, video, etc.) For the Class of 2009, commencement followed the signing day. Dolan kept a copy of his commencement address, some of which follows below:

Pride of 2009, don’t worry I have no advice for you. All my useful advice was used up on the first day of fifth grade. Work hard. Be good. Think. Got that? Cool — all done with the advice.

Instead I would like to take this opportunity to share some of what I am grateful for on this very special day.

Fifteen years ago Mike Feinberg and Dave Levin founded KIPP for the same reason GCP exists — kids and parents and teachers deserve it. Nine years ago Mike Feinberg left a message on an answering machine (that’s how old we are — neither Ms. Sutton nor I owned a cell phone) asking if we wanted to build a school. Without Mike and Dave’s courage and commitment to kids this day would not have happened.

Our other friends and family from KIPP: In the 8 years since our founding KIPP has grown to serve 16,000 kids. Some of these people you may never have met but they worked tirelessly to help our school and others.

I am grateful for the scary, tenuous, traumatic first four years of the school. In a joyous moment like today it’s easy to forget how hard this was and how far away today seemed even in eighth grade. Standing here it was all worth it.

I am grateful for all of the mistakes the young men and women on this stage made. I know I often didn’t behave like I was grateful for your mistakes but whether it was failing a test, smacking your lips, or getting caught kissing on the bus in sixth grade (give a look) each mistake you made ensured that the Prides that followed would have a better school.

I am grateful for each of the 1440 or so mornings I was able to greet you at the buses. Whether you are one of the bright and chipper or the groggy and sullen, seeing you stumble off those noisy, dirty buses reminded me every day that we were all struggling to make this work. It reminded me that you had finished your homework only a few hours before hearing alarms ring, that your moms and dads were hustling you out of bed and signing your planners, how in the words of President Obama’s mother “this was no picnic for any of us.” This may be the hardest part of next year for me and many of us here I don’t really know what it’s like to start my day without seeing you guys.

Possible interjection: this speech is really where 2009 takes revenge on me for all the times I made them cry by making me cry like a baby.

I am grateful for Red clay—one of the nastiest substances on the planet, responsible for ruining countless school carpets and pairs of shoes your parents bought. No matter how much grass we plant we will never get rid of the stuff and it will always remind us where and how we began. This school and Pride emerged from a field that used to hold sharecropper’s cabins.

I am grateful that one of you will takeover or create the school that ensures everyone who starts in 5th grade commences their college journey in 12th.

I am grateful for the way in which you (the families, teachers, and students of 2009) have shaped children’s lives that you may not even know.

Meet the Pride of 2009

Here are some snapshots of the Pride of 2009, some interviewed in person, others by phone. A fair number of the founding class returned to teach at KIPP, in Gaston or elsewhere. Overall, KIPP Gaston employs 20 of its graduates (out of a staff of 150) as teachers. Said Sutton: “We are thrilled that so many found returning to their communities a worthwhile option and are leading in our classes, our college counseling department, and our offices.”

Ashley Copeland

In every class, there are some students everyone seems to know something about. That’s Ashley Copeland, for sure. Her classmates know she went to Duke University. They know she owns two properties in the Washington, D.C., area and aspires to own more. They know she’s the social butterfly of the class, organizing the organizers planning the class’s 10th reunion in 2019. And they know that she’s never taken the traditional path, even today, as she holds a 9-to-5 job at the investment bank Morgan Stanley, helping brokers expand their reach via social media platforms, and then for two or three nights a week waitresses at Founding Farmers. “I’ve always worked two jobs; that’s all I know.” That was true in high school and college as well. In high school, she waitressed at the Cracker Barrel just off Interstate 95 near Gaston, and during breaks from Duke, she returned to that Cracker Barrel.

“I knew I was going to work either on Capitol Hill or the White House. There was no other option for me.”

— Ashley Copeland

Originally raised in Suffolk, Virginia, Copeland and her mother moved to Garysburg, North Carolina (a town near Gaston that’s even smaller), when she was 10, a move prompted by her parents getting divorced. Her mother bought a double-wide trailer and parked it on land owned by her grandmother in Garysburg. Unimpressed by the Garysburg schools, her mother was on the lookout for something better and came across a brochure about the new KIPP school starting up. As first, Copeland was hesitant about making a change. “I was already bitter about moving.” But she made the move, embraced the intense, college-oriented academic focus drawn up by Tammi Sutton and Caleb Dolan, emerging as an A-average student, accepted by both the University of Pennsylvania and Duke. She started at Penn, didn’t like it, and transferred to Duke, which she loved, and from which she graduated (debt free, thanks to grants and scholarships) as a history major.

After graduation, she waitressed at Cracker Barrel for six more months, enough time to buy a car. With that car, she could make weekly drives to Washington, D.C., three hours from Gaston, to search for jobs and a new life. “I knew I was going to work either on Capitol Hill or the White House. There was no other option for me.” She started her search on the Hill, going from office to office looking for work. Soon, using a contact from a trip she had made to Egypt while still in high school, she landed a job with then-North Carolina Sen. Kay Hagan. Unable to live in expensive D.C. on just that salary, she began waitressing at Founding Farmers, a job that came in handy when Hagan lost her bid for re-election in 2014. For a year, that was her full-time job. She loved it. “I earned more money, met amazing people, and had fun. I backpacked in Europe for two months, went skydiving, and saved enough for a down payment for my first home in Dupont Circle.”

Copeland has traveled far from her days as a little girl living in a double-wide trailer in rural North Carolina. As the deciding influence, Copeland points to her years at KIPP Gaston, especially fifth grade, when Sutton and Dolan convinced all the students that they would not only go to college but come away with a degree. “I don’t think I would be talking to you if it weren’t for them. I am blessed and grateful to have had that experience.”

Brittney Jeffries

Jeffries and her older brother grew up first in tiny Garysburg and later in Roanoke Rapids, a small city near Gaston. Her mother worked in a factory, her father as a custodian. Today, her mother works as a detention officer in a county jail, her father as a custodian in a school in Roanoke Rapids. She first came across Tammi Sutton and Caleb Dolan when they taught her brother during their time at Gaston Middle School. When her brother stayed late at school, she found herself, and her mother, there as well. “They had a great relationship with our family.”

When Jeffries was in fourth grade, Sutton and Dolan told the family about a new school they planned to found. Jeffries was ready for something fresh. “I had had a rough year at my old school and thought, ‘Wow, school is boring.’ I was tired of looking at textbooks. I was ready for something new. I loved Miss Sutton and Mr. Dolan as teachers. I thought they were cool and funny. I was like, ‘This is going to be the best, that they will be my teachers.’”

After graduating from KIPP Gaston, Jeffries went on to East Carolina University, where she majored in communications and public relations. After a year working at a county visitor’s center trying to figure out her future, she visited her old school and asked Sutton for career advice. They discussed her love of music, and Sutton said they happened to be looking for a middle school music teacher. Preferring to work with smaller children, she ended up as a first-grade teacher at KIPP Gaston. (Her older brother teaches at KIPP Halifax, an expansion school for the Gaston network.)

After two years of teaching, Jeffries decided she needed a change. “I had this epiphany, thinking, ‘Wow, I’ve never lived outside North Carolina. I want to try something different.’” That something different turned out to be teaching at a KIPP school in Philadelphia, her first bigcity experience. “It’s like the complete opposite of anything I’ve ever known. But Philly has this home vibe about it. It’s not overwhelming like New York City. In West Philly, I feel like I can wrap my head around it.”

Jeffries keeps in touch with many of her classmates, including Ashley Copeland, with whom she talks at least once a week. Her memories of school in Gaston center on how the teachers made learning fun. “I remember in fifth grade learning vocabulary words with Miss Sutton and she turned it into a drama class, where we got to act out the vocabulary words. I loved that. I was learning and having fun at the same time.”

Teia Jenkins

Jenkins grew up in Littleton, North Carolina, a one-stoplight town about 20 minutes outside Gaston, raised by a single mother who worked as a corrections officer. She’s unsure how her mother heard about KIPP, but one day she made it clear that a school transfer was happening. No questions asked. Why? Jenkins isn’t sure, but she assumes her mother concluded that KIPP offered more opportunities for her daughter. “The school I was going to is well known, but for the wrong reasons.”

At first she wasn’t happy about attending KIPP, mostly because the long commute meant she had to wake up around 5 a.m. “At that time, I was riding to school with one of my teachers who got there well before school started.” What she was learning seemed over her head, at least by the standards of her previous school. But Jenkins eventually settled in, earning mostly A’s and B’s and entering East Carolina University. “Initially I hated it. Freshman year was like going to high school all over again. I remember skipping classes thinking, ‘I already learned this material in high school.’”

But Jenkins persisted and earned a bachelor’s degree in industrial distribution and logistics. Her first job was at a FedEx store, followed by a job at a grocery distribution center. Today, she works for Acme United, a distributor of office supplies and other materials, in Rocky Mount.

Jenkins recalls her years in the Class of 2009 with fondness. It was a small world then. Tammi Sutton (whom she still refers to as Miss Sutton, despite the generally accepted practice of alumni, after earning a bachelor’s degree, calling her Tammi) was her basketball coach and also taught her English, math, and history. “We were the first class. We were the guinea pigs, so everything we did basically was the first time it was done there. So we created a lot of memories. KIPP definitely gave me a lot of stepping stones.”

Monique Turner

Turner was raised in Roanoke Rapids, just outside Gaston, the daughter of a social worker and a disabled veteran, neither of them college graduates. She was in eighth grade in her neighborhood school when she heard about KIPP. “There was this buzzing about it, with people talking about their kids going to a school that provided college prep. I knew I wasn’t being challenged in school, that I wanted something more, so on my own I decided I wanted to apply to KIPP. I brought the information to my parents, and they were completely down with it.” So in the ninth grade, she became part of the Class of 2009.

“I knew what the public school system wasn’t providing for me.”

— Monique Turner

Her transition into KIPP was smooth. “Even though my parents weren’t college graduates, they instilled in me very early what I needed to do to be academically successful. By the end of second grade, I could do my times tables and multiplication. I knew what the public school system wasn’t providing for me.”

Turner graduated near the top of her class and had two prestigious college acceptances, Rice University in Texas and Wake Forest University in her home state. When she won a full-ride scholarship to Wake Forest, the decision got easier. Going to Rice would have meant paying an extra $12,000 a year. “My parents and I negotiated, but they said, ‘Look, you don’t have to pay anything if you to Wake. So you’re going to Wake.’”

Freshman year at Wake, however, was a “complete culture shock.” Suddenly, she was surrounded by mostly privileged white students. “I was in class with kids who had been in private school all their lives, who vacation in Prague and Greece, whose parents are lawyers and doctors and judges. It was a humbling experience. Wake Forest taught me what it means when people are able to be successful because of the privileges they have been given.”

Academically, Wake Forest was a struggle, both in the rigor of the classes and Turner’s sense of self-esteem. “If I could do it over again, I would have more confidence in myself, believing that I’m capable.” Fitting into the social life was difficult as well. “Going to a predominantly white institution made me feel like an outcast, even if that wasn’t necessarily the truth. But that was my mindset. So now, at 27, I understand that to be successful our mind has to be in a certain place.”

Over time, her college experience improved, especially with opportunities to travel abroad, spending six months in South America, where she was able to bond with a full range of Wake students. “I was able to make connections with individuals that I will have for the rest of my life.”

Turner majored in political science and volunteered for Barack Obama’s 2012 campaign. After she graduated, Sutton offered her a job teaching at the KIPP Halifax school, which she accepted.

One of Turner’s most prominent KIPP memories is of high school graduation, where she gave a speech. “The message that I had in 2009 was to stay connected.” And that’s what she still does. “We’re adults now, and every one of us has our own lives, and we’re choosing to start families. When I see my classmates, at the grocery store or at the bank, doing adult things, I always ask how they are doing, whether they are taking care. I want to know where everyone is.”

Victoria Bennett

In 2001, Bennett was a fifth-grader at Garysburg Elementary when she heard about the new school. “There was this community buzz about a new school, and I also remember people talking about being afraid that our school would get shut down because it was low-performing, and had been for many years. My mom just kind of came home one day and signed us [her and her brother, Derrick] up and said, ‘This is where you are going.’”

Bennett clearly recalls her reaction to the first few days of school: “This is insane.” First, she had to start school at KIPP a full two weeks before her friends who stayed in district schools. Then, the principal, Caleb Dolan, insisted on shaking the hand of every student who stepped off the bus. “When it came to my turn, what was running through my head was, ‘Why is this man shaking my hand? Is he going to be my principal or my teacher?’”

During those first two weeks, there were no classes, only lessons in learning the KIPP school culture, especially about the school’s informal motto, The Pride. “We were told the strength of The Pride is the lion, and the strength of the lion is The Pride.” Learning the culture was part of “earning” their classes, they were told.

The oddest part of that orientation, and something every member of the Class of 2009 talks about, was the startling demonstration Dolan and Sutton choreographed to show the importance of “tracking” — following with your eyes the speaker, whether it be the teacher or another student. With all the students assembled in the makeshift cafeteria, Dolan and Sutton suddenly began running around and Dolan leaped through the cafeteria serving window. In hindsight, it wasn’t clear to anyone exactly what that was supposed to mean, but it left an impression. “At that moment I realized, ‘Oh, man, these people are serious. They are really, really serious.’”

Bennett stuck it out and did well. During her senior year, she was accepted at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and won a full-ride scholarship. Arriving there was rough, however. “It was a culture shock.” Unlike Gaston, where she saw the same people every day for 18 years straight, at Chapel Hill, she would go for an entire day and not see a single person she knew. It was the first time she was truly a minority, and the first time she was surrounded by students from well-off families. Once, her study group met in the library and then decided to go out to upscale Ruth’s Chris Steak House to get dinner. “I looked up the menu to see the prices, and there were no prices listed … that’s not a good sign.” She declined the offer.

Another social impediment: her country dialect. “The biggest thing for me was enunciation, because in the country everything runs together and you don’t say full words. You say ‘cuz’ rather than ‘because.’ You just say ‘fridge’ rather than ‘refrigerator.’ Or ‘mote control’ rather than ‘remote control.’”

Another major challenge from those days: In her senior year, she became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter.

There were other minority students at Chapel Hill, but not many from a tiny town in rural North Carolina. When she spoke up in class, she could tell nobody was listening to what she actually said. “Their mouths would drop open and they would look at me like they were in a daze and say, ‘Oh my God, your accent is so cute. Could you say that again?’”

Another major challenge from those days: In her senior year, she became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter. “I was the first one [from the Class of 2009] who became pregnant while in college. I remember most people from back home saying, ‘OK, you have a baby. You’ve got to come home to raise that baby.’” Naturally, she turned to her many KIPP mentors for help, but she found their reaction was complicated. “I never felt like I wasn’t supported by KIPP, but I kinda felt like people were hesitant and kind of standoffish when it came to me. They weren’t sure how to take it. And today I understand it better than I did back then, because they don’t want to make it seem like you’re praising and encouraging people to go to college and get pregnant.”

Bennett knew that if she came home to raise her daughter, she’d never make it to law school, which was her dream. Encouraging her to stick with her academic ambitions was Tammi Sutton. “She was like a mini-cheerleader in the back of my brain, telling me I could do it. And she was constantly pushing resources to me.” The inner voice prevailed. Bennett returned to school and graduated on schedule. After graduation, Bennett went to North Carolina Central Law School, part of the historically black university. That’s where she decided to shed her country diction after she noticed it was a problem when applying for internships. “We’d be talking about something and they wouldn’t acknowledge anything I said. Then they’d say, ‘Are you from New Orleans?’”

She graduated from law school in 2016 and lives in Raleigh, where she negotiates contracts for Advance Auto Parts. “I absolutely love my job.” Bennett is the only lawyer to date to emerge from the Class of 2009. She was part of KIPP’s first Alumni Leadership Accelerator fellowship program, designed to give first-generation college graduates a tailwind that wealthy students automatically get through family connections in starting their careers.

For Bennett, the program paid off, hugely. At the time she applied for her current job, she lacked the experience Advance was looking for. But after the first Accelerator session in Chicago, sessions with a career counselor taught her how to present herself, how to find connections she didn’t realize she had. She found those connections, presented herself perfectly, and won the job.

One more bit of history about Bennett that’s important to know: She joined KIPP Gaston’s board. “Initially, it was hard to voice my opinion because the people who were on the board were people who had watched me grow up and still viewed me as a kid.” But that changed, again with her newfound confidence from coaching that was part of the Accelerator fellowship. “That [coaching] changed the perspective for me. Now, I’ve taken the approach that it was my school. I know it better than anyone else. Who better to speak to the people in control?”

Lomar Osbourne

Osbourne is a KIPP Gaston alum who seems to have stepped out of central casting and into the role everyone always wanted him to play: college counselor for KIPP students there. But he’s also an unlikely player to have made it this far. He’s the second of 12 children, raised by his grandmother, in circumstances on which he treads lightly. Says Osbourne: “A lot of things” happened. If students there ever needed a role model, someone who walked a walk probably tougher than their own family life, there’s Osbourne, whose path through college was not an easy glide and whose real-life lessons are rooted in rural North Carolina. What’s also interesting about Osbourne is that he didn’t even arrive at KIPP — a suggestion from a family friend who was active at the school — until he was in 11th grade. For many teens, that transition could have been rough, but Osbourne said he was accustomed to change. “I just kind of kept my head down and did the work.”

At graduation, he had acceptances from several universities, including Chapel Hill and Wake Forest. An offer of a near-full ride at Wake Forest made up his mind, and he graduated from there four years later, with a major in religion and minors in politics and business. While applying for jobs, he also volunteered at KIPP Gaston, helping students who had dropped out of college and needed to be readmitted. The volunteer work went well, and KIPP asked him to apply for a job as a college counselor. He did, and that’s where he has been ever since, handling both college advising and teaching the college prep classes, which at KIPP are pretty much the same thing.

Osbourne understands the unique family circumstances experienced by the students at KIPP Gaston. Especially in high-need families, there’s always an issue about how far away from home the students should go. The families want them close by, but the colleges with the best graduation rates are often far from Gaston.

Often, Osbourne has to play the “mean counselor” role, beginning with the speech he gives to the departing seniors every year. Going to college, he tells them, requires them to be selfish. Translated, that means sticking to the graduation plan and resisting getting drawn into family issues back home. “A lot of our kids come home because of family emergencies or tragedies, things they feel compelled to be here for. So I’m the mean one, who asks them, ‘How much can you really do?’”

Again: Stick to your college graduation plan. That matters. A lot.

Today, Osbourne serves as director of college counseling at KIPP Gaston.

Chevon Boone

Boone grew up in Garysburg, the middle of five children in a family that always struggled to make ends meet. Her mother worked in “hospitality,” which ranged from motels to nursing homes. Her father was “the community handyman.” Later, they both worked at group homes for troubled youth. “From their perspective it’s like, ‘Hey, we raised five kids successfully together. Let’s help raise somebody else’s kids.’”

Boone’s older siblings attended Gaston Middle School, where they met Tammi Sutton and Caleb Dolan. “They were like the coolest teachers. Growing up, we didn’t have steady transportation, so if they would stay after school Mr. Dolan would drive my brother home after track practice or Miss Sutton would drop off my older sister after cheerleading practice. On many nights, my mother would make dinner and they would stay over for dinner. They were pretty much an extension of my family.”

So when Sutton and Dolan decided to launch a school, Boone signed up immediately, starting in fifth grade as the future Class of 2009. One of her favorite memories was a dressing down Sutton gave the school, probably when she was in ninth grade, after a series of arguments among students. Sutton gathered everyone in the gym and pulled out some cash. Boone’s memory from ninth grade was that Sutton showed everyone $100, but Sutton assured me it was $10. “Then she gave us a lecture, saying she wasn’t in teaching for the money; she was in teaching for us, to better us and help us develop into better humans. So she’s talking about it’s not for the money while ripping up the bills, one by one, and letting them fall to the floor. She kept ripping the bills while saying we had to work as a team, work in unity, and don’t let disagreements hinder us from our goals. But the only thing I vividly remember was her tearing up the money right in front of us. It was pretty dramatic, definitely the talk of the afternoon.”

Boone was a mostly A-average student, and she had great college acceptances from which to choose: Duke University, the University of Pennsylvania, Rice University, and Emory University. She chose Penn, which offered a full-ride scholarship, but she found the transition rough. “For the first year and a half, I hated it,” said Boone. Most of the students came from high-income families and arrived knowing exactly what professions they intended to pursue. Boone, on the other hand, was unsure about careers and spoke with an accent. “Like, with the first two or three words out of my mouth, there would be times when even the professor would stop me and say, ‘Hey, where are you from?’”

She also stood out as a low-income student, a fact that was most noticeable during spring break when the wealthy students headed off for vacation. “They would go all over the place, to California, Canada, Miami, the Caribbean. Some would even travel to Europe over spring break.” At best, Boone made it back to North Carolina to see her parents. Back home in Gaston, few knew anything about Penn, even where it was located. Many confused her Ivy League school with Penn State University. But because it was out of state, everyone considered it exotic.

Things got better at Penn for Boone when she joined a theater group and a dance group. “I was able to step out of that quote-unquote ‘black bubble’ and was able to see the full diversity Penn offered.” Most interesting to her was the diversity among the black students. “It was my first time meeting black people who were not African-American. They were coming from Africa or the Caribbean or from a Latin country.” As an African-American woman from a small town, she was a minority within a minority.

Boone was also fortunate in landing paid internships while in college, including at the KIPP Foundation and Relay Graduate School of Education. After graduating from Penn, she taught in Newark for Uncommon Schools before taking a job with Valor Academy Middle School, a KIPP school in Washington, D.C. In 2018, she joined Relay in D.C., where she instructs new teachers.

Joshua Edwards

Edwards grew up in nearby Roanoke Rapids, with his twin brother, Justin, and six other siblings. “Apparently the older you are, the greater the … chances you will have twins. My mother was 40 when we were born, my dad 44.” His father worked for the railroad, sometimes as a cook, other times checking track. His mother mostly stayed at home but later worked in hospice care.

When Edwards was in the eighth grade in a Halifax County middle school, his mother grew worried about recent gang violence. She wanted something new, had heard about the KIPP school, and told the twins they were going. They both enrolled in ninth grade.

“I didn’t know what to expect. Miss Sutton led a two-week course where they drilled us on everything we had missed for the last four years. There were some academic pieces, but the main part was school culture: ‘If you’re going to be part of this school, here’s what you need to know. Here’s why we exist.’ I enjoyed it; it was totally different from what I experienced in Halifax schools.” Once classes began, the academic differences became apparent. “At my old school, all I had to do to get A’s was to sit down and be quiet. It was pretty simple. At KIPP, you had to work hard for your grades.”

Memories of high school? Edwards cites two school pranks he treasures. Once, everyone in a civics/economics class pooled their cell phones, set them on vibrate, and hid them behind the ceiling tiles. Then, drawing on the cooperation of someone in the front office, during the class, the cell phones went off, one after another. “The teacher is looking around and they’re starting to buzz like crazy now. He thought it was coming from the ceiling so he took a broom, lifted a panel, and one of the phones fell out. He was confused, but in the end when he found out it was a prank, he wasn’t too mad.”

The bigger prank was directed at Miss Sutton. The classmates pooled their money, and someone went to UPS and bought bags of packing peanuts. Her car was always unlocked — she often loaned it out to students to run errands, so it wasn’t hard to sneak out and fill the entire car with packing peanuts.

In their senior year, Edwards and his twin brother both went to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on full-ride scholarships, and after graduation, they both returned to KIPP to teach, with Joshua teaching math and Justin teaching technology at the middle school. “I had never wanted to be a teacher, but once I graduated, I thought about how I could give back to the community. That was something that Miss Sutton always instilled in us” — one of the reasons why many KIPP Gaston alumni ended up teaching. “I remember her saying all the time, ‘It’s great for you to go out and get yours and do great things, but what are you going to do to give back?’ I started thinking about it personally. I’m an introvert, a really shy person, and so having to teach and be in front of people every day would give me the character skills that I think are necessary. So I figured, why not?”

Has that worked out? “It has. It absolutely has.”

Chris Escalante

Escalante is important to include among the profiles because while 61 percent of the Class of 2009 won bachelor’s degrees, that doesn’t mean everyone did. Chris hasn’t. College success statistics usually wrap up at the six-year mark, but Escalante’s journey represents a good reason to look beyond that time frame. In May, he’ll pick up his bachelor’s degree, pushing the class success rate up to 63 percent.

One of Escalante’s classmates described him as a “hot mess” in high school, a characterization he probably wouldn’t disagree with, at least for portions of his life. His father, a native of El Salvador, swam across the Rio Grande River to enter the U.S., met his mom in Maryland, and began a family. But things didn’t work out well, for all kinds of reasons, and his mother ended up moving to Gaston, without his father, living in public housing very near the current KIPP Gaston school. Why Gaston? Because it was a really cheap place to live. Escalante didn’t meet his father until his sophomore year of college, shortly before his dad was deported back to El Salvador.

As Escalante puts it, his big break in life came when he “failed” second grade in Gaston because he was more interested in dreaming and doodling than schoolwork. “My teachers came to my mother and said I wasn’t mature enough for the third grade; that if I did second grade again I might get the daydreaming out of my system.” By repeating second grade, he was perfectly positioned several years later to enter the Class of 2009 at KIPP Gaston, which he did, pushed by his mother, who looked at the longer hours at KIPP and concluded this was a good way to keep her son on the right path. “When you’re going to school from 9 to 5, you can’t get into trouble.”

At KIPP, some of the daydreaming persisted, but the intense you’re-going-to-college message slowly sank in. “Even if I didn’t want to go to college, I mean, it was the only thing I had known. The only field trips I had been on were to colleges.” A talented trumpet player and jazz musician, Escalante took advantage of some KIPP-sponsored trips to jazz programs. In the end, he chose Norfolk State University. There, by his own description, he became a textbook case of what happens when a tightly controlled high school student, who was in school every day until 5 p.m., lands on a college campus where classes often conclude at noon. What to do? Escalante held it together for one semester, but by the second semester he fell into the party scene and by the second half of his sophomore year lost his scholarship. “I was out.”

Escalante went back home to Gaston, moved in with his mother, and worked a series of jobs, ranging from a packing job in a peanut factory to stocking shelves at a Food Lion. “My supervisor at Food Lion would say to me, ‘You’re so smart, why are you working here?’” Eventually, the pressure got to him, and he enrolled in community college to push up his GPA to the point where he could return to a four-year university, North Carolina’s Elizabeth City State University, from which he will graduate with a degree in music. His dream job: a high school band director, probably at KIPP.

This is an excerpt from the new Richard Whitmire book The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending Diploma Disparities Can Change the Face of America. See more excerpts, profiles, commentaries, videos, and additional data behind the book at The74Million.org/Breakthrough.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation funded a writing fellowship that helped produce The B.A. Breakthrough and provides financial support to The 74. The 74’s CEO, Stephen Cockrell, served as director of external impact for the KIPP Foundation from 2015 to 2019. He played no part in the reporting or editing of this story.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter