Report: More States Are Giving Students a Say in Education Policy

At least 33 now include positions for youth reps or advisors to their state boards of education or school chief’s office, up from 25 four years ago

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated Sept. 20, correction appended

An increasing share of states are including student perspectives in education policymaking, a new report finds, but making sure those voices are diverse and have real power can remain a challenge.

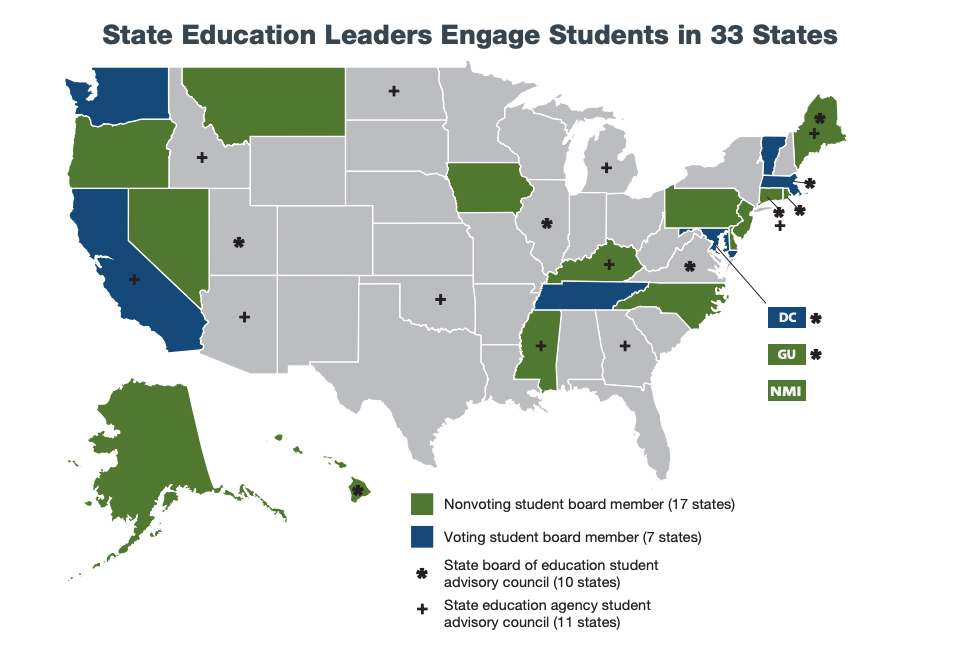

At least 33 now include formal positions for youth representatives on their state boards of education or as advisors to their state boards or their state superintendent’s office. That’s up from just 25 four years ago, according to an August brief by the National Association of State Boards of Education. The organization is the only group that carries out nationwide audits of youth representation at the state level of education policymaking, and its prior update came in 2018.

Over that span, three states — Mississippi, Kentucky and Delaware — added positions for student members on their state boards where no such role previously existed. Five more — Virginia, Idaho, California, Arizona and Michigan — created new student advisory councils to guide their state boards or their state chief’s office.

“Students have a very valuable perspective,” said Celina Pierrottet, the report’s author. “Now our state leaders are starting to recognize the importance of capturing that experience and learning from it.”

The pandemic may have spurred some of the recent uptick, with California and Idaho explicitly citing the coronavirus as the reason they created the new positions.

“The effects of COVID-19 have been widespread and created impacts unlike anything that we have ever seen. Youth have experienced their education in ways that are unprecedented, including pivoting to virtual learning,” California State Superintendent Tony Thurmond wrote as he announced a new Youth Advisory Council in September 2021.

“As we reimagine education, we hope to have young people working alongside California’s education professionals and policymakers to build a better tomorrow.”

Rainbow Chen spent two years as a student representative on Vermont’s state board from 2015 to 2017. Over that time she weighed in on several high-pressure topics, from the possible closing of schools amid declining enrollment to how underlying issues like poverty can lead to disparities in standardized test results. Her views, she believes, helped her colleagues understand issues from a more nuanced lens.

“[As] someone who identifies as low income and someone who isn’t from a typically prosperous school in the state, I felt like I had a really great perspective,” she said. “The state board that I was on was extremely welcoming and really desired my voice. I felt very respected, like an equal.”

Still, Chen said, it was achieving voting power in her second year in the role that seemed to force adult members to give her “a lot more respect.”

Vermont is one of only six states, plus Washington, D.C,. that give youth members a vote on the board, according to the report.

Massachusetts is another that grants voting privileges to students. But despite that power, Daniel Brogan, who served as the sole student voting member on the state board in 2013-14, recalled officials still not treating him as they did their adult colleagues. During downtime before meetings started, while other members spoke to each other about policy proposals, “usually with me it was more superficial questions, like, ‘How’s school going?’ Not, ‘What did you think about this [policy]?’” he said.

Like Chen, Brogan grew up in a low-income family with parents who had not attended college. Commuting from his home in Barnstable on Cape Cod to Boston for meetings often posed a challenge.

“There were times where I genuinely had to choose between having school lunch money for the week or having enough money for bus fare to get up to Boston,” he said.

Once a month, the board would convene on Monday evenings until as late as 10 p.m. and again Tuesday morning at 8 a.m., meaning Brogan would return home at midnight only to wake up at 3:30 a.m. to catch the bus back to Boston.

To attend meetings, the youth rep was forced to miss so much school he received a truancy letter, he said. But he never skipped a board meeting, because “optically people would notice and be more skeptical” of a student, he said, even though several adult colleagues missed at least one meeting.

It’s often those types of challenges that keep low-income or otherwise underserved youth from participating in local government, said Beverly Leon, CEO of Local Civics, whose organization empowers young people to become civically active through lessons and real-world projects.

“There’s many barriers [to participating in policymaking] that young people face. And of course, there are additional barriers that young people with fewer resources and access to financial and social capital face as well,” she said.

At the local level, just 14% of the nation’s 495 largest school systems include one or more student members, according to a National School Boards Association 2020 survey. Even when those bodies do include youth perspectives, it’s frequently the voices of those who are more privileged and well connected, said Leon.

“More often than not, the young people that are entering those spaces either have parents or folks in their community that are bringing them there.”

To ensure a wider array of perspectives, several state boards of education have diversity requirements that guide who they select as student representatives, the national association report finds. Washington, D.C.’s board requires youth representation from the majority-Black Wards 7 and 8, whose residents have been historically underrepresented in city leadership. And the Utah State Board of Education requires that the 15 students comprising its advisory council hail from a balanced mixture of geographies, socio-economic statuses, ability levels, academic achievement levels and school types, including traditional public, charter and online.

“The folks that are most impacted by a policy decision or challenge in a community should have a voice in crafting what an effective solution should look like,” said Leon. “It makes for more effective policy.”

Indeed, youth policymakers or advisors have scored several key wins across the country. While Brogan was on the state board, Massachusetts enacted the nation’s first rule requiring schools to take student feedback into account in their teacher evaluation processes. In 2006, a youth advisory council to the Maine state legislature proposed and successfully lobbied for the passage of a bill guaranteeing visitation rights to siblings placed in separate homes by child welfare. And in 2016, Washington state’s youth legislative advisors were able to get a bill passed into law helping students experiencing homelessness land housing and access to other needed services thanks to the creation of new homeless liaison roles in schools.

Within school communities, when youth voices are truly listened to and reflected in policy decisions, it can have a positive impact not only on campus culture, but on students’ academic outcomes like grades and attendance, according to a recent study published by researchers at the University of California, Riverside and Northwestern University.

Yet still, youth nationwide remain highly disconnected from political participation and civic education. Only nine states and Washington, D.C. require a full year of government courses, while 31 call for just a semester and the remaining 10 mandate none at all, according to a 2018 report from the Center for American Progress.

That can translate into low levels of engagement stretching into adulthood, Brogan believes.

“When you turn 18, you’re expected to have a switch flip and say, ‘Now you can vote, now you can organize,’” he said. “Unfortunately, I think that leads to … people being completely disenfranchised.”

“It’s really hard to start showing up at [policymaking] spaces if you didn’t know that they were open to you as a young person,” added Leon.

But when youth do gain experience with civic engagement, the impacts are often potent. Just ask Chen what her dream job is.

“I still want to be the Vermont secretary of education in the future. That’s still something I really aspire to be, much influenced by my experience on the Vermont State Board of Education,” said the policymaker-in-training. After graduating from Brown University with a degree in education policy in 2021, she is now studying for a master’s in teaching at Harvard.

Brogan, too, remains committed to uplifting youth voices within schools. He’s studying for his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota, researching case studies where governmental bodies included feedback mechanisms for youth perspectives. His master’s thesis was titled: “Where are the Students in Student Voice?”

Someday, he hopes to continue that work as a professor, but to collaborate with students in the process.

“I really want to make it my life’s goal to work with students. … I don’t want to do things for students — I want to do things with them.”

Correction: The new student advisory boards were created to guide their state boards of education or their state superintendent’s office. A previous version of this article only cited the state boards.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter