Financial Literacy Now a Graduation Requirement for All Rhode Island High Schools After Years of Student, Teacher Activism

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Seven years after students from a small, suburban Rhode Island high school successfully advocated for the adoption of financial literacy standards, state lawmakers have made proficiency in personal finance a requirement for high school graduation, beginning with the class of 2024.

Signed by Gov. Dan McKee on June 1, the law creates a Dec. 31 deadline to develop and approve state-specific consumer education and personal finance standards. By the start of the 2022-23 school year, all public high schools in Rhode Island must offer a standards-aligned course.

“It’s very aggressive to get these standards up and running in the time frame that we have set out, but we know that it’s really necessary,” state Education Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green said. On average, Rhode Island graduates have the second-highest student loan debt of any state, at $36,193.

Having met with students statewide who felt they weren’t prepared to go onto college, and given the pandemic’s impact on student engagement, the commissioner told The 74 this moment was the time to solidify what they had built momentum behind for years.

“[Students] felt like this was something that they were being shortchanged [on]. So we made it a point to push this agenda.”

Rhode Island approved the national Council on Economic Education standards in 2014. On average only about 5 percent of Rhode Island students receive financial literacy education, according to the state education department, given that schools could choose whether or not to adopt the curricula.

Last year, senior Saloni Jain took a personal finance course in a hybrid learning setup, with three days of learning online, at the suburban East Greenwich High School. She said course simulations, like completing mock returns on TurboTax and creating a budgeting spreadsheet, kept her engaged during virtual learning.

“We were getting paychecks — how do we put that money towards a 401(k) and pay all our bills and pay down our credit card or student loan debt? That was really helpful to visualize, you know, how we might live in the future,” Jain said. “It was just a one-semester course, but it honestly changed the way I think a lot.”

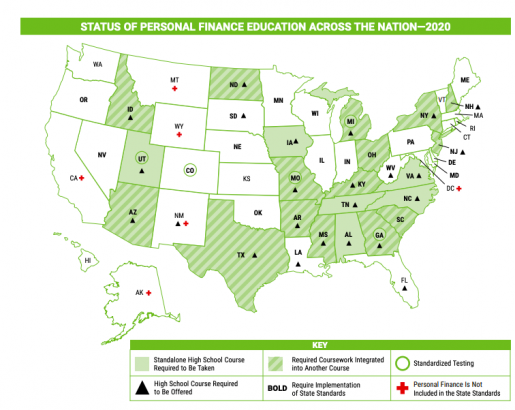

Nationally, 21 other states have some version of financial literacy standards, which may be incorporated into math or civics classrooms, though only seven require that a standalone, full-semester course be completed before graduation.

In 2021, over 25 states have introduced bills strengthening personal finance education. Advocates contend that literacy is key to breaking cycles of poverty, particularly as the younger generation deals with economic fallout from the pandemic. When loans, budgeting and debt management are explicitly explored during the school day, young people are exposed to life-changing information as they head into adulthood.

A 2018 study from Montana State University researchers showed that financial literacy graduation requirements result in lower credit card balances and high-interest student loan debt for lower -income students, and decreases in private loans for higher-income students. Working- and lower-class students who took financial literacy courses were also able to work less while enrolled in college, which could encourage college persistence and graduation. Expanding access to personal finance courses can help improve racial wealth gaps and support homeownership down the line.

Even within states considered to have the strongest standards and requirements, students seek more real-world connections to prepare them for the future. Whitman Ochiai, who recently graduated from high school in Alexandria, Virginia, described his mandatory course as “more broad than it was deep”.

Left wondering about retirement decisions, building a balanced budget and the intuition behind large purchases, he started the MoneyEd podcast in 2019 to explore thosetopics. He said there’s been increased interest throughout the pandemic, likely with more students working and families facing economic uncertainty.

“A lot of times the only people who have access to this information are the people who would have had access to it anyway,” Ochiai said. “Especially for first-generation college- goers and students, and parents that may not be homeowners, this is a pathway for them to have a deeper understanding of finance.”

Some Rhode Island teachers created elective courses in their schools in recent years, heeding students’ desires and seeing how financial literacy may enable connections to hard-to-grasp concepts like compounding interest. Before now though, funding and implementation was left to individual teachers or schools to prioritize.

Samantha Desmarais teaches math, financial literacy and computer science at Central Falls High School, which serves predominantly low-income Latino and Black students in a working class city just north of Providence. She hopes the legislation will open the door to financial support from the state for credentialing and hiring, building more capacity to teach the subject.

Otherwise, she said, “there’s going to be disproportionality between the districts that are able to shimmy around their budgets or their staff and make it work, and the districts that are weighted under all of these other things.”

Desmarais teaches about three sections of finance per year; enrollment is always on the higher side even with its elective status, at about 25 to 30 students per class. This fall, she’ll also teach a section for language learners, which introduces students to American money systems and credit.

“If you enjoy learning something today, spread that news and talk about it with your friends. There’s no reason why talking about money has to be this taboo subject,” she tells her students.

Advocates say that personal finance education provides an opportunity for students to break down any stigmas about money conversations before they head into large financial decisions, like student loans, car ownership and credit card debt. Lessons learned may also make their way home and support families facing economic challenges.

“I look at the state’s implementation of this guarantee of a financial education as sort of being a gateway to some meaningful engagement with families,” said Pat Page, vice president with the Rhode Island JumpStart personal finance coalition and a business educator.

Page, Rhode Island’s former teacher of the year, has been a vocal advocate for broader financial education for years, and was one of the first in the state to teach a standalone course. She supported students, including Sunny Sait, in testifying in favor of broader financial education to the state legislature — in 2014, 2019 and again in 2021.

Though Sait took Page’s class two years ago, he said he still uses the concepts daily. Currently on a gap year after graduating this spring, he’s opened up a Roth IRA, and budgets his internship paycheck to make sure he can still afford things he loves, like karate.

“My mindset definitely shifted a little bit from thinking of money in terms of things, but instead thinking of money as a means for growth, saving and investing. I really had my focus shift from purchasing, like being a consumer, to becoming an investor.”

Many describe the effort to make financial literacy a reality for all Rhode Islanders as both a grassroots and grasstops effort, pushed by students and teachers, but also state leaders, like Treasurer Seth Magaziner, who helped introduce the legislation.

“The strongest advocates who worked very hard to get this bill passed were teachers and students. Students who very much wanted this to be taught, and teachers who are ready to teach it,” said Magaziner, who began his career as an elementary school teacher and recently announced his run for governor.

The treasurer and education commissioner both see the law’s signing as phase one of creating a broader financial literacy landscape in the state — their hope is to expand lessons to middle and elementary grades. The education, Magaziner says, will make a particular difference in Rhode Island.

“We do have a large rolling immigrant population, students who are English language learners. We have one of the highest poverty rates in the Northeast. Financial education is not a panacea, it’s not a cure-all, but it is an important part of the puzzle for how we solve these inequities, and correct them.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter