The Mastery Transcript Consortium Has Been Developing a Gradeless Transcript for College Admissions. This Fall It Gets Its First Test

When D. Scott Looney was tasked with opening the first experiential learning campus for Cleveland’s private Hawken School, some of the traditional ways of grading students started making less sense to him: letter grades, standardized testing, GPAs. In fact, he started to find them “toxic.”

“It makes great shorthand for sorting kids, but it’s not good for growing kids,” Looney said.

These are problems many innovative schools across the country have been tackling as they shift to practices like project-based or experiential learning in an effort to make education more relevant and engaging. One of the most challenging questions for these schools becomes figuring out ways to translate learning experiences onto a transcript for colleges.

So Looney set out to reimagine the high school transcript, one without letter grades or GPAs but instead with measures of academic abilities and skills like collaboration, communication and persistence. Over time he found that dozens — and then hundreds — of other schools were interested in this kind of transcript. In 2017, they formed the Mastery Transcript Consortium, and over the past two years they have been building and testing their product. Now, 250 schools have joined from across the U.S. as well as countries like Thailand, China and New Zealand, according to the consortium’s website.

Many of the members are private schools, but the consortium has also added two dozen public schools. This fall, five schools will be using these transcripts for their students to apply to college, a first-time test that will shed light on how they are being received.

“Admissions decisions are reduced down to … a couple of factors,” said Stacy Caldwell, executive director of the Mastery Transcript Consortium, citing GPAs, SAT scores and class rankings. “[None] of those really reflect the richness of what the student is doing.”

But moving beyond grades in college admissions can be a contentious issue. After the consortium launched, some criticized them for creating a system that could favor wealthy and elite schools. By eliminating a common metric from transcripts — the GPA — admissions officers wouldn’t have an easy way to measure or compare students, meaning it might be easier to fall back on admitting students based on the brand name of their schools.

“It makes it hard to compare students, which is kind of the whole point of admissions, is comparing students and being able to say this student did better than that student,” said Gabriel Rossman, associate professor in UCLA’s sociology department. “Whereas, if I show mastery in overcoming adversity and you show mastery in critical thinking, how are they supposed to compare that?”

While other efforts to reimagine how colleges admit students have been launched, Mastery’s was the first dominated by private schools. But the founders argue that their transcript, by considering a more holistic view of students, is actually a step forward when it comes to equity.

Inside the new transcript

If you were to look at a handful of traditional-style transcripts from the top students at several different high schools, they would probably look very similar, with high GPAs, dozens of As, and a list of AP classes, said Mastery’s chief product officer, Mike Flanagan. But the mastery transcript uses design elements plus an interplay between different kinds of credits to help their students stand out.

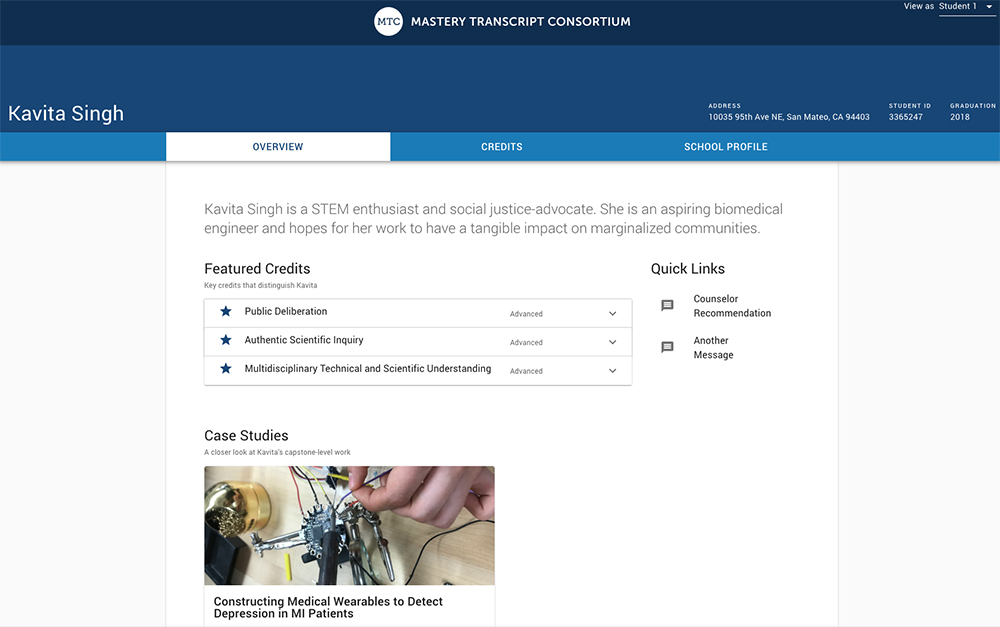

The current mock-up of the mastery transcript looks a bit like a high schooler’s LinkedIn. On the first page is a brief description of who the student is, such as “STEM enthusiast and social justice advocate” with “hopes for her work to have a tangible impact on marginalized communities.” Students can highlight some of their credits on this page that they think make them stand out from their peers, or include a portfolio of some of their best work.

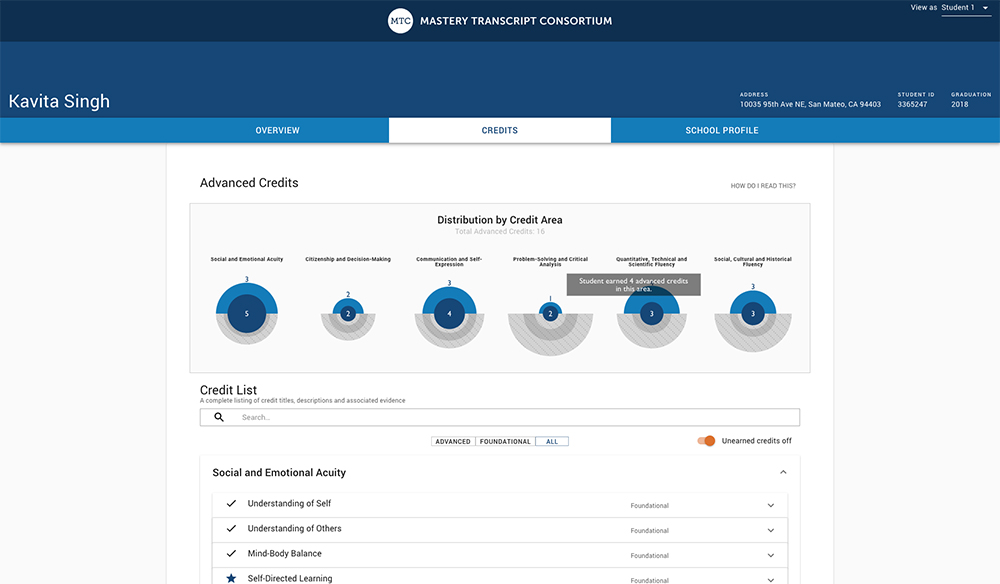

The second tab of the transcript delves into credits a student has earned, and is by far the most jarring for a new viewer. Large bubbles span the top of the page to show how many credits a student earned. Schools get to choose which credits show up at the top. Some may stick to traditional subjects like STEM or history, while others are a bit more inventive: “social cultural and historical fluency.” This is also a place where schools can show how their students have learned other skills like critical analysis, social-emotional learning, problem-solving or decision-making.

“We know that students need to build a broader range of skills that, frankly, we aren’t telling them [about] right now,” Caldwell said.

To help their students show individuality from their other college-applying peers, the transcript differentiates between “foundational credits” and “advanced credits.” Foundational credits are those a school requires, but there are a myriad of advanced credits students can choose from to show how they stand out and are different from their peers in a certain topic.

Students use these advanced credits to demonstrate how their interests separate them from the pack. One student may be drawn to political science and will likely earn more advanced credits in this topic, while another student might be more excited by theater or art and would have more advanced credits in those areas.

Showing these credits isn’t enough — for a college admissions officer to understand them, the consortium needs to provide context in the transcript design. That’s why the group has been experimenting with gray semicircles at the bottom of these credit balloons that show how many credits in a topic other students at the applicant’s school earned.

This is all part of a collaborative effort between the consortium’s schools to take equity seriously, Flanagan said.

“If we don’t come up with a way where the credits themselves signal the students’ accomplishments independent of the issuing institution, we run the real risk of replicating these sort of structural inequities that are already there,” Flanagan said.

Still, some schools that are a part of the consortium don’t want to include this feature, because they want to get away from comparing and ranking students with this new transcript. So the consortium has built a tool to allow this feature to be turned on or off by individual school.

However, some are concerned that the act of not comparing students gives elite schools an advantage. Eliminating or obfuscating grades is something the elite schools of the world have always practiced, argued Catherine Rampell, in a Washington Post column from 2017 about the consortium.

“Admissions at top colleges is a zero-sum game, after all,” she wrote. “If signal-jamming by the Chapins of the world sufficiently confuses college admissions officers into accepting more of their students, fewer spots will be available for other schools.”

But some argue that the current admissions process is already far from equitable, that a school’s brand can play a role in admissions, regardless, and that reducing students to test scores and GPAs far from encompasses the whole child.

“A GPA is not an equalizer; a GPA is a diminisher,” Looney said. “[Kids] have been distilled to a number and they’ve been distilled down to a very narrow range of things that can be measured on a standardized test.”

The Mastery Transcript Consortium, a nonprofit, did not disclose the cost of membership but said that it’s priced on a sliding scale and that financial assistance will be given to those who need it.

College admissions and the whole child

College admissions officers have very little time to spend with a high schooler’s transcript. Maybe two minutes. Maybe five. That’s why the Mastery Transcript Consortium has been working to make sure its design is decipherable as quickly as possible.

But even with this tight time crunch, admissions officers said they are still interested in getting a holistic view of their student applicants. Some are even involved in similar efforts themselves.

David Hawkins, executive director for educational content and policy at the National Association for College Admission Counseling, works with Reimagining College Access, an organization based at the Learning Policy Institute that is trying to find a way for performance assessments — like portfolio work or large projects — to be part of the college admissions process. The group hopes this can improve educational equity and better inform admissions decisions.

Michael Reilly, executive director of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers, said the Mastery Transcript Consortium may run into problems at state schools if those colleges require a student to have taken a very specific course load of subjects, but overall he sees the organization as part of a broader movement in both high schools and colleges.

“It remains very promising, and I think it is the direction that secondary and postsecondary schools are going to: a much more comprehensive record of student learning than simply a transcript,” Reilly said.

That’s because transcripts don’t do a good job of describing learning outcomes, and that’s not just a problem for college admissions but also for employers, Reilly said. Reilly’s organization is working with others on a project called the Comprehensive Learner Record, which is trying to develop a better way to communicate what a college graduate’s career-ready skills are.

However, accepting students based on this holistic approach doesn’t require a lift just from the admissions officer side. It also means alumni and college presidents must be OK with not being able to advertise how many incoming freshmen earned perfect GPAs or high test scores or ranked at the top of their class. It requires a culture shift.

“We’re really going to have to challenge some of those long-held points of pride and points of reference to expand the conversation even further,” Hawkins said.

Goodbye to all grades?

In the 2019-20 school year, a handful of students at five schools will be submitting their high school transcripts using the mastery transcript. Other schools that are part of the consortium will still be testing out how the transcript works.

Kyra Weatherwax, who will be a senior this fall at Enosburg Falls High School, a roughly 330-student public school in Vermont, is one of those students who plans on using the transcript for college applications. Not all of her high school peers are doing this — only a small group opted in to try this transcript. Weatherwax decided to test it out because she’s been excited about Vermont’s move toward proficiency-based learning, though frustrated by its slow progress. This was an opportunity for her to show what she’s learned on her transcript, highlighting her interest in social studies, government and civics.

“I am a person who really values personal autonomy and deciding your own way in life, and I could talk all day about how much I hate the one-size-fits-all mentality in education,” Weatherwax said.

Still, she’s hesitant about how colleges will accept the mastery transcript. Before she submits her applications, she plans to reach out to colleges to see if they will be OK with her turning in this new transcript or if they’d prefer her more traditional one.

“It would be helpful to have a clear list to say, ‘These are colleges that will accept this transcript,’” Weatherwax said. “I do anticipate mentioning it: ‘I have two transcripts, and I was a guinea pig in this innovative grading movement.’”

Weatherwax will still be taking the SAT. Because transcripts — traditional or not — are separate from tests like the SAT or ACT, students who apply to colleges that require the entrance exams still have to submit their scores.

Building 21, a nonprofit that operates two schools in Philadelphia and Allentown, Pennsylvania, are public school members of the Mastery Transcript Consortium. These competency-based schools were in the process of developing their own gradeless transcript when they discovered the Mastery Transcript project, and they abandoned that effort to join the work of a larger group, said Tom Gaffey, Building 21’s chief instructional technologist.

“In both Philly and Allentown, we’ve been waiting for the opportunity to have some kind of transcript that shows true progress and true mastery,” Gaffey said.

For Gaffey and his team, this transcript filled a need — communicating to schools how their students are learning through a competency-based system that doesn’t adhere to typical class schedules, credit hours or grades.

A century’s worth of research on grades has shown that they are a good indicator of how well a student will do in college and how well they’ve learned academic content. Grades can also show some measure of soft skills, like persistence and motivation. Whether or not they are the best metric doesn’t negate the fact that they have been a helpful one for college admissions, more so than standardized tests: “This quality of graded achievement as a multidimensional measure of success in school may be what makes grades better predictors of future success in school than tested achievement,” the 2016 report authors wrote.

Susan M. Brookhart, professor emerita at Pittsburgh’s Duquesne University, helped write the report on grades. Grades aren’t always equal across schools and bias can sometimes creep into grades, she said. Although she is skeptical that the work of the Mastery Transcript Consortium can be scaled up to every school across the country, she said she still applauds the organization for trying.

“I’d love to give the Mastery Transcript Consortium room to experiment,” Brookhart said. “There is something to be said for students to be given multiple opportunities to show what they know and multiple ways to do that.”

While a few schools from the Mastery Transcript Consortium will be submitting transcripts that don’t include letter grades or GPAs for the first time this year, there’s another school outside the consortium that already did.

One Stone, a small, free, private school in Idaho, submitted a very different kind of transcript for its 39 high school seniors last fall to 76 colleges. This “growth transcript” also does not include grades but is instead divided into quadrants of learning objectives: traditional knowledge, mindsets, creativity and professional habits. Their success may be a good sign for the consortium: 51 colleges sent acceptance letters to these students and offered $1,169,860 in scholarships for their first year at schools like Seattle University, Colorado State and the University of Arizona, according to Chad Carlson, One Stone’s director of research and design.

But getting colleges acquainted with One Stone’s transcript was no small effort. School leaders met with dozens of college admissions officers, gave tours of their school, called colleges to walk them through what their transcript meant and flew around the country to attend meetings.

“As to be expected, there was some nervousness [from parents and students],” Carlson said. “But they also saw the power of what we were doing. We told them we were working very hard to get this out into the world and to work with college admissions so our students can have the same advantages, if not greater.”

One Stone even considered joining the Mastery Transcript Consortium, because of its collective power to do the work of meeting and explaining the transcript to college admissions officers. Although it would have taken One Stone less time, the school leaders ultimately decided not to. As a new school, they wanted to develop their own unique growth transcript, and, one day they might even consider making a consortium of their own.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter