Fearing ‘Fiscal Cliff,’ District Leaders Reluctant to Hire Full-Time Teachers

Rand survey suggests federal pandemic relief aren’t districts’ silver bullet for teacher shortages

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Many school superintendents and district leaders are reluctant to hire full-time teachers with temporary federal pandemic relief funds, even as many schools face shortages, according to new research.

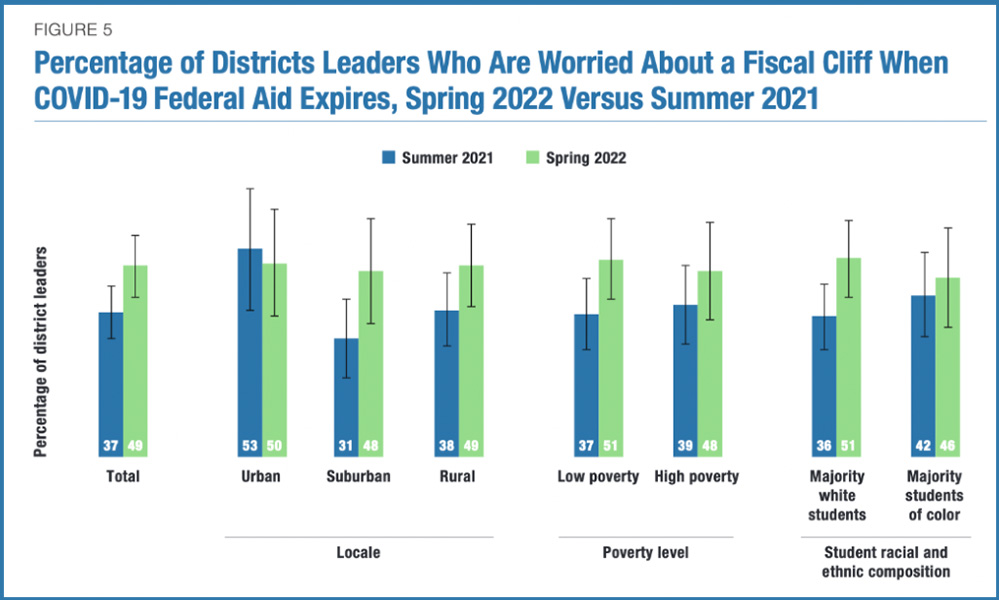

Nearly all districts concerned about a looming fiscal cliff are taking measures to prepare for it, likely to hit when federal pandemic relief aid ends in 2023, according to Rand’s latest American School District Panel survey.

The findings, from a survey of 291 district leaders polled this spring, suggest school officials may not be using relief aid exclusively for salary bumps or full-time teachers because it is not sustainable.

While districts are hiring staff well beyond pre-pandemic numbers, the positions expanding the most are substitutes, paraprofessionals and tutors — with a quarter surveyed saying they are “avoiding certain staff hires to prevent later layoffs,” the report stated, alluding to full-time teachers.

Many are also using the funds to roll out short-term tutoring and summer programs for students’ academic recovery, or make one-time investments in school infrastructure.

About a sixth of districts are adding to “rainy day funds” and hiring non-teaching personnel on yearly contracts for “flexibility.”

Researchers also believe the hiring boom is the key factor fueling higher vacancy numbers in the field — not a “big quit” of qualified educators.

Districts that employed, for example, 100 teachers in 2019, are now seeking 120 new hires to meet students’ increased academic and mental health needs.

“You could imagine that it might be easier on districts to scale up and scale down their number of substitutes than their number of classroom teachers,” said Melissa Kay Diliberti, an assistant policy researcher at Rand.

Districts also received a range of funds dependent on their student population — creating a widely varying picture of pandemic-era hiring from district to district, even within state lines.

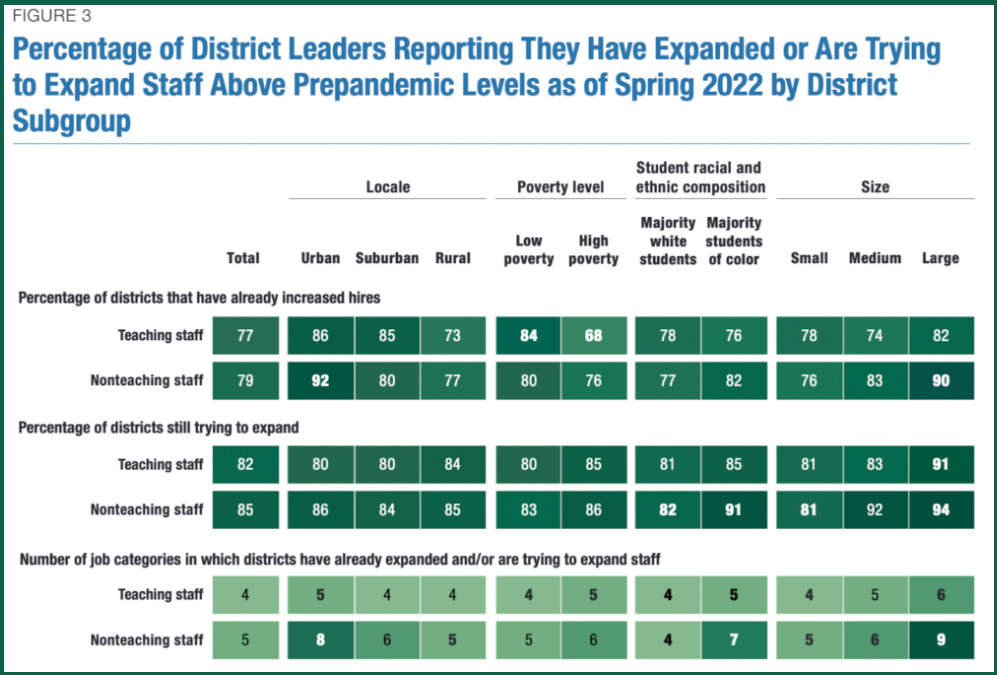

Large, urban school districts serving mostly students of color are trying to hire more staff, said Diliberti. “These are the schools that probably got the most extra money and that are therefore able to do the most expansion.”

Seven critical findings from Rand’s report:

1. Nearly 80% of districts have already hired staff beyond pre-pandemic levels

Most of America’s districts are still trying to expand — 94% of large districts, for example, are expanding non-teaching staff, like bus drivers, counselors, paraprofessionals and tutors. And on average 77% of districts have now hired on more teachers and/or substitutes than in 2019.

Districts’ huge increases in staffing are straining education labor markets, not an exodus from the field, the Rand report states.

“The stories that have tried to tell this, you know, ‘slew of teachers have been leaving the profession and that’s what’s causing the teacher shortage’ is not quite true,” Diliberti said, adding that there’s still cause for concern about educators’ low morale. “Even if they’re not actually leaving the profession, teachers who are unhappy at work aren’t good for students, right?”

2. About half of district leaders predict a looming “fiscal cliff”; 87% of those concerned have taken steps to prepare

More superintendents and district leaders are concerned about an impending fiscal cliff this year than in Spring 2021. And about half of leaders are concerned, across all school types: urban to rural, whether serving majority students or color or majority white students.

“It’s not necessarily inevitable — districts are aware of the possibility of a fiscal cliff and they can take action like in the coming years to try to prevent it,” Diliberti said.

Strategic one-time or short term investments, such as investing in school infrastructure, launching summer learning programs or hiring in yearly contracts, “will allow them to more easily reduce the load of staff if and when in the future they don’t have the money to keep them at their current levels,” she added.

3. Substitutes, paraprofessionals, and tutors are the jobs that have expanded the most since the pandemic began

The positions have a direct connection to the pandemic’s strain on schools. Substitutes were districts’ lifeline when faced with numerous full-time teachers in quarantine, while paraprofessionals and tutors “address the unfinished instruction from several years of pandemic-related disruptions to schooling.”

Bus drivers are also in high demand; about a third of districts have not yet increased their number but are trying. Rand’s report notes a possible reason for the shortage of drivers could be the extensive qualifications and concerns about working in group settings during the pandemic.

4. Low-poverty districts are more likely than high-poverty districts to have expanded staff above pre-pandemic levels

Notably, 68% of high-poverty districts have already increased their teaching force beyond pre-pandemic numbers. In comparison, 84% of low-poverty districts have expanded ranks.

Researchers think the gap could be due in part to a historical trend: higher-poverty schools are harder to staff. Experienced educators are in demand and are more likely to be recruited by wealthier districts with better working conditions and better pay.

“Teacher labor markets [are] not one thing. Some districts … even before the pandemic started, struggled to hire teachers — in particular, high poverty schools, and sometimes schools in rural areas,” Diliberti explained. “It’s always harder for districts to staff those positions and to staff teachers at the secondary level, especially in math and science.”

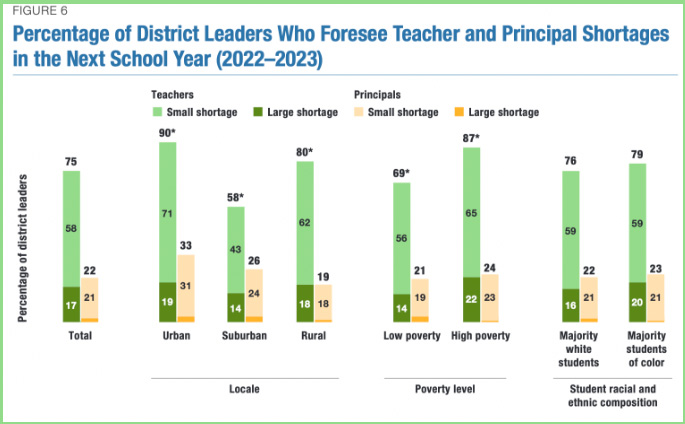

5. 17% of districts anticipate ‘large’ teacher shortages next year

While a majority of leaders expect small labor gaps to impact schools next year, large shortages are concerning urban and high poverty leaders the most.

Suburban and low-poverty district leaders do not anticipate any large shortages.

On the whole, large principal shortages do not seem to be on leaders’ radar.

6. Findings suggest a current national substitute shortage

Over half of districts have expanded substitute teaching staff beyond 2019 levels, and 76% are still trying to expand in anticipation of the fiscal cliff and to meet pandemic-related staffing shortages.

“In some ways I don’t feel like this substitute teacher shortage is as new or as sexy of a story as a teacher shortage because it’s kind of always been a problem…I think that’s one of the reasons it’s gotten minimized,” Diliberti said.

Sixty percent of districts increased pay or benefits for substitutes. The average daily rate is 6% higher than in 2019 — now about $122 per day versus $115 per day pre-pandemic. Urban districts have and continue to pay the most: $146 per day in the latest school year, about $30 higher than rural districts.

7. 90% of districts changed operations because of shortages at some point during the 2021-22 school year

While some changes were short-term, like asking admin to sub for teachers in quarantine, researchers say the figure is an indicator that even this latest pandemic school year was not at all business as usual. Nearly all American districts had to adapt to major challenges.

“Operational issues are really just taxing us at every level… As an example, [there were] three different schools on three different days that I had to close because I had too many call-offs and not enough staff to replace them, or substitutes to replace them,” one superintendent told Rand.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter