School Leader Crisis: Overwhelmed by Mounting Mental Health Issues and Public Distrust, a ‘Mass Exodus’ of Principals Could be Coming

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As Derek Forbes began his third pandemic school year as a high school principal in Washington state, he was facing an uptick in disruptive behavior — kids talking back to teachers, getting into disagreements with their peers.

Perhaps, he thought, young people had lost some maturing time in pandemic isolation, since the behavior was more typical of younger students. Or maybe, like him, they were exhausted.

The mental health positions he’d posted stayed vacant for a fifth month. He and his principal colleagues in the Meridian School District were now logging upwards of 60 hours a week, taking on responsibilities of counselors, nurses, subbing as teachers, and food service workers. All while being verbally attacked at local school board meetings over curricula and mask guidelines.

“My students aren’t learning the way I want them to, they’re dealing with their own mental health issues that I can’t help them with, my staff are struggling with those same things. And more and more stuff just continues to pile on,” he said.

For the first time in his 22-year education career, a depleted Forbes has thought about leaving the job he loves, to pursue district leadership.

“I always thought that I would always stay in education, and I have no doubt that I will continue… But, I thought about what else might be out there. And I never thought I would do that,” he said.

His experience is hardly rare. Across the country, many principals are preparing to leave the field altogether.

A survey of more than 500 this fall by the National Association of Secondary School Principals has found nearly four in ten expect to leave their post within the next three years. More than a third will leave education as soon as they can find a higher-paying job.

Dubbed a looming “mass exodus” by NASSP, numbers were even higher for principals with four years or less on the job: 62 percent of early-career principals said they will leave within the next six years. Many others are nearing retirement age.

The crisis has hit principals of color, women and those leading schools with higher proportions of lower-income students and students of color particularly hard. They are more likely than their peers to experience job-related stress during the pandemic, a new RAND study found.

According to NASSP’s fall survey, 91 percent of principals were very or extremely concerned about student wellness, more than any other challenge (in comparison, mask mandates had about 51 percent very or extremely concerned). More than a third said there’s not adequate student services staff, like nurses and counselors.

“…For people to start saying, ‘Man, you know, I’m not ready to die. I’m not dying yet but this thing is killing me,’ really scares me,” said NASSP CEO Ronn Nozoe. “Because people, especially our members, don’t say that stuff. And they don’t say it lightly and they sure as heck don’t say it publicly.”

The surveys and widespread stories of principals’ well-being plummeting point to the need for mental health support, mentorship and leadership development programs for principals, said Nozoe.

Principals told The 74 the exodus may begin as early as the end of this school year. Some may want to leave mid-year but, understanding the stress it would cause for their schools, are waiting until summer break.

Nozoe has seen red flags for the profession throughout the pandemic: Fewer candidates are entering training, higher education and teacher preparation programs. Superintendents are also experiencing burnout and reaching retirement, so some principals will go on to district roles.

But the biggest flag, he said, is that teachers across the country have expressed the same care and concern that they express for students, now for their supervisors.

“It’s the first time I’ve really seen it – our teachers saying, ‘We’re struggling, but man, I’m really worried about our principal,’” said Nozoe.

“‘He or she is getting beat up, and he doesn’t look good or she doesn’t look good. They’re all stressed out and I don’t want to lose her or him.’”

Strategizing on how to better support students and staff mental health has had a ripple effect. Principals are now pointing the spotlight on themselves, taking stock of their own well-being.

“I have sought out and have been seeing a therapist, because I think it’s important — not just for me as a principal to talk to my kids about [their] mental health — it’s also important for me to walk that walk,” said Michael Brown, president-elect of NASSP’s Maryland chapter and principal at Winter Mills High School.

Brown said the “highly politicized nature of education” has taken its toll on the state’s educators, many of whom never fully clock-out, making evening calls and communications about the latest pandemic guidance to families. “You struggle to have positive days, positive thoughts.”

‘I had to choose myself’

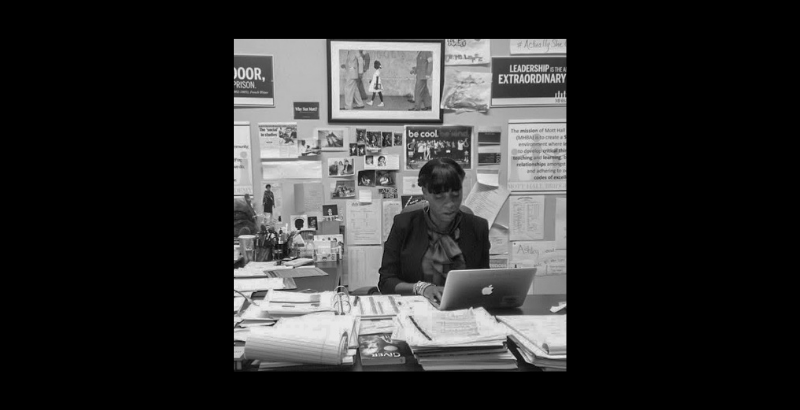

Nadia Lopez, former principal of the Mott Hall Bridges Academy, a middle school in Brooklyn’s Brownsville neighborhood, criticized the lack of support for principals of color during the pandemic and constant race-based violence.

While trying to keep students on track academically, their schools were disproportionately taxed by racism, police brutality, COVID-19 deaths and pandemic job loss.

“Not once was there a convening of leaders to say ‘we recognize that there’s an issue that’s happening across our nation, and you all are having to shoulder a lot of this,’” said Lopez.

Now a leadership coach, she continually sees the impact of unsupportive superintendents and disproportionately concentrated student needs. On New Year’s Eve, she got a call from one distraught New York assistant principal of color, who regularly subbed for teachers on top of her usual duties. She was finally signing her resignation papers, accepting another offer. Another in California left her post mid-year to become a consultant.

They and dozens of others have recounted their health issues, insomnia and depression to Lopez, their mentor who’d opened up about her own decision to leave the Brooklyn middle school she founded and led for a decade. She resigned in June 2020 after developing a crippling kidney disease from the professional stress.

“I had to choose myself and say, this no longer aligns with who I am as a person. It doesn’t represent who I am as a parent. It doesn’t represent the leader that I’ve been to my scholars and telling them that education is a form of liberation,” Lopez told the 74. “It perpetuates the idea that you accept abuse when you shouldn’t have to.”

My experience as a school principal right now… pic.twitter.com/ji6Dq5jHd9

— Greg Moffitt (@Greg_Moffitt) January 20, 2022

Clear across the country, educators in Wyoming are tapping out, too.

This school year alone, Principal Brian Cox has hired seven new teachers; at least two “left the field of education altogether, mid-year.” His workday starts at 2:30am to address daily staffing challenges.

“Some principals feel like the job is becoming untenable. Like there is no way to win,” said Cox, who heads up Cheyenne’s only predominantly low-income middle school.

With media and public officials disrespecting their expertise, those in the profession feel, “like your boss had it out for you, the community hated you for the job you do,” he said. The fallout will create a “massive void … of interventions, of instructional and behavioral frameworks.”

Strengthening the pipeline

Top of mind for all principals The 74 interviewed is creating more balanced workloads, to change the reality that they cannot succeed without sacrificing their own health.

States must also back ways to recruit and cultivate the next generation of teachers and administrators, Brown said. Investing funds in teacher retention alone will not have the domino effect it once had.

“They think it’s just going to be a natural pipeline. But if you see somebody leave… it’s going to give people hesitation…‘I’m not exactly sure now, because this person, I really looked up to them…and they weren’t able to handle it. How am I going to be able to handle it?’” Brown said.

Principals on the brink are also looking for more support from states to match students’ growing wellness needs, to provide services that go beyond what schools can offer, such as partnerships with licensed mental health providers or clinics.

Having district leaders act as thought partners, who can help them manage shortages or partner with universities to rebuild educator pipelines, has become a priority for principals debating their futures, said Lopez.

“We need to have good programs to teach them. We need to have good mentoring programs to support them. We need to have great support systems in the districts to do it,” said Nozoe. “That all has its infrastructure, and you can’t just snap your fingers and build it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter