How New York Students Are Restoring the City’s Harbor One Oyster at a Time

Thousands of middle schoolers get their hands dirty as part of the Billion Oyster Project’s efforts to rebuild long-lost reefs

By Josh Sanburn | August 9, 2020Over the next several weeks, The 74 will be publishing stories reported and written before the coronavirus pandemic. Their publication was sidelined when schools across the country abruptly closed, but we are sharing them now because the information and innovations they highlight remain relevant to our understanding of education. (You can find our full pandemic coverage here)

On a bright morning last fall, a bus full of middle school students piled into Erie Basin Park in Brooklyn, New York, elated to be outside on a school day, and a bit nervous about the day’s assignment: pulling oysters out of the city’s harbor.

As the students gathered in the park, their teacher issued instructions: Help reel in a half-dozen oyster cages that have been submerged in the basin’s waters, open the gates, and tally the number of live and dead oysters they see (including any sly sea creatures who might’ve made their home inside).

“If their mouths are open, it means they’re dead,” said 11-year-old Brielle Hall, one of the students from M.S. 88 — a middle school serving grades 6 through 8 in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn — as she and her classmates began measuring each craggy oyster one by one.

One student found a predator — an oyster toadfish — and named him Jerry. “Can I keep Jerry?” a boy named Sal asked his teacher.

“We think we found a shrimp!” another student yelled.

As the students counted the number of oysters in each cage, they also began remembering the lessons about the marine mollusks they learned in the classroom.

“We basically killed them off,” 11-year-old Simon Boon-Blankinship said. “And right now we’re trying to revive their species here.”

These middle school students are part of an effort across New York City called the Billion Oyster Project, an ambitious undertaking founded in 2014 to restore New York’s harbor as one of the world’s great oyster reefs.

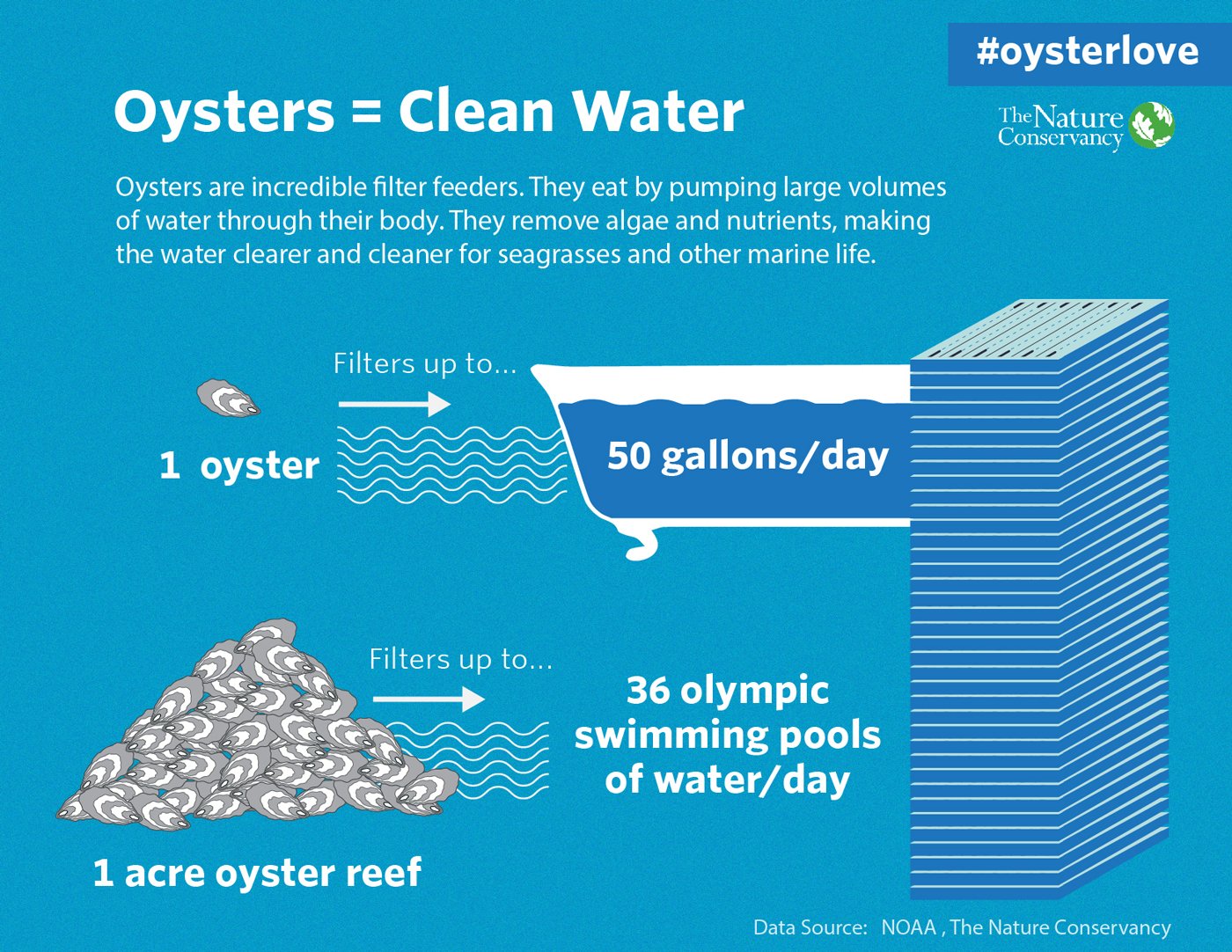

“I think that they’re yummy,” 11-year-old Jack Allspaw said as he measured one of the live oysters and began ticking off what he had learned in class. “I don’t think that they have a brain, but they do have a heart. And then they filter the water. To get rid of sewage and stuff.”

Jack Wasylyk, a sixth-grade teacher at M.S. 88, said most of his students, like Jack, hadn’t experienced pulling actual animals out of the water and studying them.

“We’re creating a generation of young people that are aware that New York Harbor is an ecosystem,” Wasylyk said. “So a lot of these kids are putting their hands on wildlife in New York City for the first time today, and it’s a powerful experience that stays with them.”

BOP’s goal is to restore New York’s harbor to its former status as one of the world’s great oyster reefs by putting 1 billion oysters in the water by 2035. To achieve such a monumental task, each year BOP enlists the help of hundreds of students from dozens of schools — often public schools that have a significant number of students living below the poverty line, but also private and charter schools — from the city’s five boroughs.

At the beginning of the 1600s, when explorer Henry Hudson first sailed into what became New York Harbor — the waterway to the south of Manhattan and west of Brooklyn — an estimated 220,000 acres of oyster reefs lived and thrived there. But as New York City’s population grew, the oysters were increasingly threatened. Manhattan island itself physically expanded to support the city’s growth, destroying many of the reefs along its shores, as residents gradually ate many of the oysters still in the harbor. By the early 1900s, the city’s oysters were gone and its waterways so polluted that they were too dirty for the animals to make a comeback.

“Right now New York Harbor is sort of like a forest without any trees,” said Wasylyk. “It’s just dense, dark mud on the bottom.”

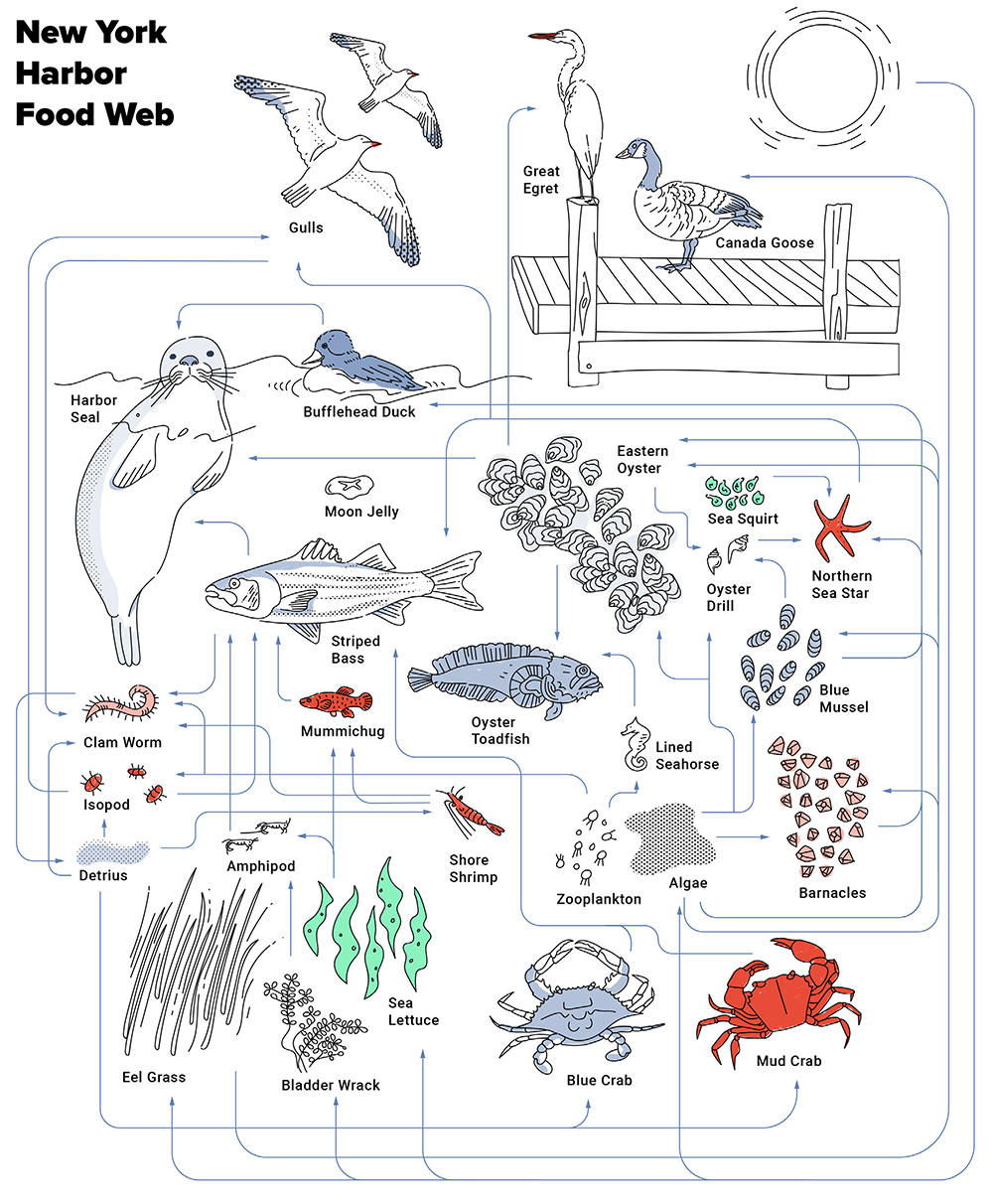

Oysters are known as a “keystone species,” meaning that an ecosystem is dependent on that species to thrive. The animals grow into reefs and form habitats that filter the water and clear it of algae, which feed on bacteria that grows from sewage and makes the water murky. That murkiness makes it difficult for grass to grow on the river bed, where other animals might be able to live. But enough oysters could filter the water and make it clearer, allowing the sun to reach the bottom, where grass might grow and other animals could feed.

Since BOP launched, the students take mini field trips throughout the year to docks and waterways around the city to analyze oysters that have already been placed in the waters by students in years past and to install new reefs themselves. Meanwhile, inside the classroom, many of the participating schools utilize a special curriculum based around oysters and the city’s maritime ecosystem. Some schools house oyster tanks, where the students can watch the animals up close, test the water quality and learn how oysters filter the water.

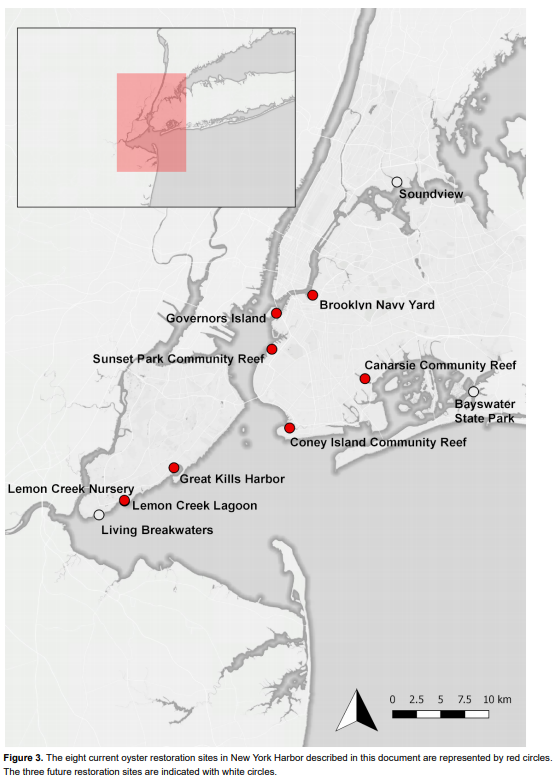

For students, the effort culminates in a year-end research symposium on Governors Island, essentially a large oyster science fair, that includes about 250 students making presentations, displaying handmade posters and discussing their findings. Ann Fraioli, BOP’s director of education, said this kind of experiential learning outside of the classroom is essential to BOP’s mission and helps students gain a fuller understanding of oysters as well as the city itself.

“Without getting your hands on something to really experience it, you can’t get as deep [in understanding the subject],” Fraioli said.

BOP first grew out of the New York Harbor School, a public high school on Governors Island, located between Manhattan and Brooklyn, that is unlike any other in the city. Founded in 2003, the school offers a curriculum that is built around maritime issues like marine biology, aquaculture, ocean engineering and professional diving but also includes traditional high school courses like English, social studies and math. In 2008, the school began installing oyster reefs around the city and began working with other schools to do so in 2012.

Two years later, Harbor School officials launched BOP as a nonprofit public-private partnership that involves city and state environmental groups, nonprofits and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The group is funded largely through government grants and contracts, as well as private individuals and foundations.

BOP partners with more than 75 oyster-serving New York City restaurants that donate their used shells. The organization provides those restaurants shell collection buckets and operates a recycling program that collects and hauls the shells to Governors Island, where they sit outside in huge piles for a year. Over that period, wind, rain, and bugs help clean the shells naturally.

Meanwhile, BOP operates an oyster hatchery, where it fertilizes oyster eggs to place on the empty shells. Each shell might include 10 or 20 live baby oysters. Then, students like those from M.S. 88 take the newly fertilized shells, often in metal wire cages, and place them into the water — generally hanging from the sides of piers on ropes. That prevents the oyster cages from dropping unsecured into the water, which would cause them to sink to the muddy bottom and likely kill off all the bivalves. If the oysters survive and thrive, they’ll grow their own shells and begin to reproduce, build reefs and populate the waters. Then, it’s often up to students from around the city to check up on them.

“Young people are being trusted to restore the natural environment where they live,” said BOP Executive Director Peter Malinowski. “We’re trying to shift the public narrative that there is a natural resource in New York and that they can make it better.”

So far, more than 6,000 students have helped BOP grow 30 million oysters on 13 reef sites covering more than seven acres across the city’s five boroughs, including areas like Coney Island, the south shore of Staten Island and the Hudson River. The project has also used 1.5 million pounds of oyster shells that would’ve ended up in landfills.

When Wasylyk’s students pulled up their cages, many saw progress. Some oysters had died, but many were alive, some huge and doing well. They also found a few living outside the cages, a sign that they were reproducing on their own.

“The fact that they’re able to thrive here is a really good sign for the future,” Wasylyk said.

Students also found some oyster predators in the cages — like “Jerry,” the oyster toadfish — also a promising marker, Wasylyk said, because it means a fuller ecosystem is starting to take root.

Bella Scott-Nuti, 11 years old and one of the M.S. 88 students, was nearby, measuring her own batch of oysters. Her group found 98 alive and four dead, not a bad haul. She said she lives nearby, in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn, and she’s noticed the murky, discolored water.

“Seeing the green water, it’s just disgusting,” Scott-Nuti said. “A billion oysters would really help.”

Lead image: A student is holding some oyster shells in the laboratory of the Billion Oyster Project on Governors Island, where environmentalists and students are working to replenish oyster stocks in New York Harbor. Thirty million oysters had already been planted by schoolchildren as of May 2020 — the public schools include the nonprofit project in their lessons — and volunteers in six years since the start of the project. (Johannes Schmitt-Tegge/picture alliance via Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter