Eating, Shopping, and Project-Based Learning: A View From Memphis’ Mall-Based Crosstown High

By Carolyn Phenicie | February 11, 2019

One semester in, this innovative, award-winning charter is finding the promise — and limits — of student-directed education

Memphis

A semester into Crosstown High’s inaugural year, leaders are learning some key lessons about their project-based charter school:

Tomatoes in the school’s indoor garden won’t yield fruit without bees to pollinate the plants.

When given the opportunity to take classes at a mall, teens will be teens.

And many students, after years in traditional schools, aren’t quite ready to totally guide their own learning.

“We kind of went to an extreme right from the beginning,” acknowledged Executive Director Chris Terrill.

“Our students are coming from 28 different middle schools, all of which are very, very traditional … and that’s the world that they’re used to living [in]. We made this rapid change. I think that was a little bit of a culture shock,” Terrill told The 74 during a visit in mid-December.

The school’s first class of 150 freshmen attend school at Crosstown Concourse, a setting as unique as its curriculum.

The sprawling former Sears warehouse sat as a vacant eyesore for two decades, but now it houses restaurants, arts spaces, health care facilities, nonprofits, and other businesses. The school counts a dentist office, the Memphis office of Teach for America, and a satellite campus of Christian Brothers University among its neighbors.

A mall is perhaps an apt metaphor for the diversity of educational opportunities afforded by project-based learning, an idea with origins in the early 20th century that’s recently seen a surge of interest. The approach lets students engage with a specific question or project over an extended period of time, picking up skills and content along the way, rather than sitting, desks in a row, and learning through direct instruction from a teacher. For example, in the spring semester, students will get lessons on genetics, DNA, and cell structure as they research high cholesterol — and a plan to get Terrill’s under control. (Seriously.)

The freer academic focus and looser rules are unique for Memphis high schools, which have focused too much on testing, Terrill said.

“It’s like this drill, drill, drill, drill, drill. They’re not seeing results … For Memphis, this is something that is really groundbreaking,” he said.

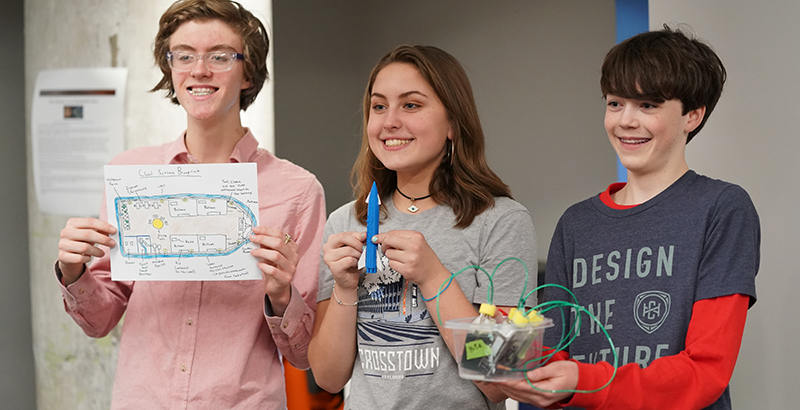

Take midterms, for instance. At Crosstown, students present their projects at a grand end-of-semester exhibition.

The students’ humanities projects focused on immigrants and refugees, the overall theme of their studies for the semester, but individual projects ran the gamut from infographics and art to biographies of immigrants and refugees the students had interviewed. For one project, a student set up a tent with one side resembling conditions in a refugee camp and the other a modern American home.

But the most memorable project, staff said, was an interactive experience that put visitors in the position of fleeing refugees, faced with the choice of what to pack as they evacuated their homes for an uncertain future. What should they take from the table before them: Food or water? Cash or jewelry? What about family heirlooms, or toys for children? It all had to fit in a carry-on size suitcase, and be packed in under a minute — the exact scenario described by a Sudanese refugee who participated in a discussion with students earlier in the semester.

Nearly all the students, 148 of the 150, completed at least one project, and the majority did both a humanities project and one for their STEM class, which in the first semester focused on traveling to Mars and making it habitable for humans.

The idea of project-based learning dates back to John Dewey in the early 1900s and has gone in and out of vogue since, said John Larmer, editor in chief at the Buck Institute for Education, a nonprofit that promotes and provides professional development on project-based learning.

About six years ago, advocates noticed a “big uptick in interest,” which they attribute both to a backlash against what’s often been called “teaching to the test” in the years since No Child Left Behind and to newer standards like the Common Core, which emphasize skills like critical thinking and real-world problem-solving, Larmer said.

Despite the increased interest, overall participation is still low, with perhaps 5 percent of schools placing a large emphasis on it, he said.

An empty warehouse and a billboard

While there had long been plans to include a high school in the 1.5 million-square-foot Crosstown Concourse, the first germ of the idea for what Crosstown High is today came from a billboard.

That billboard was for the national XQ high school redesign contest, the brainchild of philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs and former Obama Education Department official Russlynn Ali. XQ started as a contest to “dramatically rethink” the existing 100-year-old high school model.

Ginger Spickler, the founder of Memphis School Guide, a school ratings website for parents, was driving down I-55 to New Orleans, where she was slated to tour schools and meet other education advocates. After spotting the billboard on the interstate, she saw more ads for the competition at bus stops in New Orleans.

The billboard jogged her memory: Two weeks earlier, she had read an article in the local paper that said that plans for the new high school at Crosstown had fallen through.

“I just remember the tone of the article being kind of like, ‘Uh, anybody have an idea for a school?’ It wasn’t quite like that, but I knew there was a gap there,”said Spickler, now the school’s “opportunity wrangler.”

Spickler, an active parent volunteer who worked at a scholarship-granting organization for low-income children, reached out to the project developers. She and others interviewed hundreds of people in the city, from students to the mayor, and used that feedback to design the school.

“I never really thought we would get money out of it, but it just seemed like an incredible environment in which to think about what next-generation high school could look like,” she said.

Though a finalist, Crosstown ultimately didn’t win one of the initial $10 million prizes. But about a year later, XQ leaders called and offered a substantial consolation: $2.5 million, and inclusion in the XQ schools cohort. Some of that funding will go toward an artist-in-residence in the spring 2019 semester, who will also work with the arts programs at Crosstown.

At Crosstown, students’ daily schedule centers on two academic blocks: a humanities block of English and AP Human Geography, and a STEM block of biology and either algebra or geometry. Students use an “X block” in the afternoon for smaller projects and electives, like art and phys ed.

Just one semester in, standardized tests are a ways off, so it’s a bit soon to see how Crosstown’s students stack up against their peers in traditional schools. For now, many students say the school’s prize-winning diversion from tradition is offering its own rewards.

“My other school was strict, and I wanted to be able to learn my own way,” said Telicia Driver, a future interior designer who rates a poem on women’s empowerment as her best project so far.

Harper Kolehmainen came to Crosstown after being homeschooled.

“I was going to go for a normal school for high school, and then I toured and I shadowed [at a regular district high school] and it was kind of terrible,” she said. “So I wanted something less traditional.” Her favorite project so far: a 3-D computer design of a rocket that could go to Mars.

Of math and restorative justice

The staff aim to teach the students as much as possible through project-based learning, and they are evaluating success in 12 skill areas, such as critical thinking and leading their own learning.

In some cases, that approach has been wildly successful. In science, for example, students are already guiding their own learning, which is more flexible thanks to the school’s approach.

A planned year-long biology focus on Mars — whether and how to get there, and how to make it habitable for humans — shifted to just one semester after students began asking if it wouldn’t make more sense to study how to make life on Earth sustainable instead. So part of next semester’s science studies will be devoted to climate change, Spickler said.

“We can pose those questions to them, or we can put them in positions where they’re coming up with those questions themselves. I think the hope is that they want to explore those more authentically because it was their question,” she said.

But the project-based approach has proved trickier in subjects like math, said Deion Johnson, an English teacher who also recently became the school’s dean of high expectations.

It’s something every XQ school is struggling with, he said.

“For math, because the content that’s being acquired is so intricate and nuanced, you do have to take a lot of the tests, and you do have to do a lot more studying in order to refine the knowledge,” Johnson said. “A lot of that is taught in a very traditional way.”

Crosstown’s experience is fairly typical, according to Larimer of the Buck Institute. Project-based learning is generally used less in math, where real-world applications may be harder to come by, and in foreign language, where students often need a base level of standard instruction.

Also in the growing pains department, the school’s founding principal, Chandra Sledge-Mathias, left the school as of Dec. 31; Terrill cited “family reasons” as the cause. A search for a replacement is ongoing, he said in mid-January.

Another area where the school is still finding its way is in its approach to school discipline. School leaders had hoped to rely on a collaborative approach through restorative justice, Terrill said. But as school leaders learned in one recent instance, consensus can be hard to come by.

Once the school opened, students quickly began spending time in the broader Crosstown Concourse, an attractive hangout spot with its coffee and ice cream shops and vast empty — and adult-free — spaces. But what started out as an hour after school has progressed to several hours, prompting calls from building security to Terrill about students being where they shouldn’t, sometimes making out on otherwise unoccupied floors.

Terrill tried to impose a rule that students must leave the building an hour after class lets out. A meeting to resolve the issue as a community didn’t go well, and one student even raised the possibility that such a ban might not be legal, he said. After all, there’s no law saying students can’t hang out at the mall.

Instead, Terrill took a more collaborative approach. He asked that would-be legal scholar to put together a committee to walk around after school and see what’s going on, then come up with a solution everyone can agree to.

“If we can come together as a group, with community norms that we can all agree on, then I’m not going to be the jerky guy that says 4:30 and it’s done,” he said.

A diverse campus

School leaders have tried to be as intentional about shaping their student body as they were about curriculum, hoping to attract a diverse pool of students that matched the racial and economic demographics of the city.

Tennessee law prohibits the school from setting aside seats for any particular population of students; Crosstown, like other charters, runs a lottery if it has more applicants than available seats. Instead, school leaders focused their diversity efforts on targeting recruitment in specific neighborhoods in Memphis.

The inaugural class is 46 percent African-American, 34 percent white, 10 percent multiracial, 4 percent Latino, and 6 percent others.

Memphis is part of Shelby County Schools, which have a much higher percentage of African-American students, about 75 percent, according to state figures. Many suburban districts in the county serving larger percentages of white students seceded from the district after Memphis and county schools merged in 2013; the county at large was about 54 percent African-American as of July 1, 2018, according to a Census estimate.

School leaders were pleased with those numbers, along with the proportion of low-income students served, but wanted to boost enrollment among Hispanic students. That’s worked: The percent of Hispanic students who applied for the next class has increased.

“It’s just trying to get creative about where are the students that we want to serve … How do we find them? It’s hard and it’s tricky,” Spickler said.

Going forward, school leaders know what they need to tweak, from changing gardening practices to easing students into this new school model to making sure students connect with their projects. But they remain committed to their original XQ ideals, focused on diversity and project-based education. For Spickler, it’s about continually tapping into the kinds of activities that energize students about learning.

“Most of us didn’t go through a project-based experience, but we had some sort of projects along the way, and if we think back about what we remember from our educations, it’s those,” she said. “We’re just trying to create a lot more of those kinds of opportunities for students.”

Lead image: Students take a break at Memphis’ Crosstown High School, located within the Crosstown Concourse mall. (Ryan Rhea)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter