Some had children and other family caretaking responsibilities. Others started and stopped degree programs, racking up debt for careers they thought they wanted at 17.

Now, dozens of young adults in Brooklyn have moved into their own apartments or been able to provide health care for their children as they jumpstart sustainable careers as computer scientists, carpenters, health care and IT technicians, education specialists and chefs.

Paid $500 to participate in a six-week ‘13th grade’ Alumni Lab, Bushwick’s Math, Engineering, and Science Academy Charter High School grads are showing the country a model for engaging disconnected youth, those unemployed and not attending college.

“Life has not gone as they were led to believe it would,” said MESA’s co-executive director and co-founder Arthur Samuels. “…You have all of these kids who are not tethered to any institution, but the institution that they are tethered to is their high school. We need to leverage that relationship.”

“We create this artificial bright line that happens on the day of graduation: June 23, you’re our kid. June 24, we give you a diploma and you’re someone else’s problem,” he added.

The population of disconnected or opportunity youth under 25 is growing in several states including Texas, New Jersey and New York, each home to at least 100,000 respectively. Including teenagers who’ve dropped out of high school, nearly 15% of Chicago’s young people are in the same position.

The counts underestimate just how many young people are struggling post-graduation. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, those who are working under age 25 make up 44% of people at or below federal minimum wage, often without benefits.

Thousands of seats in New York City’s workforce programs designed for unemployed youth are unfilled because of recruitment and retention challenges.

Yet MESA’s workshop and coaching alumni lab is near full capacity, this spring wrapping up their third cohort in its inaugural year, with 71% of 42 young adults matriculating back to college or into a free workforce development program. About 25 students participated in the 2021-22 school year in a one-one, case management model.

Alumni say workshops feel welcoming and family-like. During one April session, a four month old napped in a stroller next to her mother. The cohort goes for lunch regularly, chatting about internship possibilities or recent TV obsessions. All sessions are taught by former MESA teachers, far from judgemental strangers.

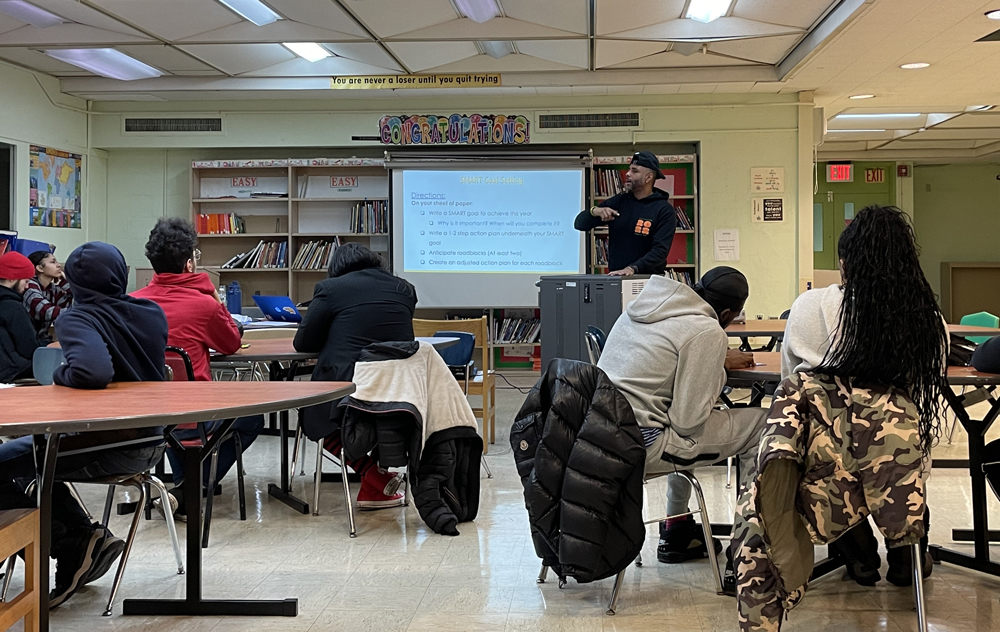

Beyond technical resume writing and interview support, biweekly 90-minute sessions explore growth mindset, self-awareness and making goals — skills that help young people, particularly alumni of color, work through feelings of inadequacy, shame, or feeling like an imposter.

“It requires a real vulnerability,” Samuels said. “…I think they’re willing to do that because of the relationships.”

Launched three years ago as school leaders encountered more and more alumni who appeared to be working low wage jobs or dropping out of degree programs to make ends meet, the model is expanding. Other Brooklyn principals have identified the urgent need to support alumni, particularly those in the pandemic generation.

MESA has formally partnered with the High School for Fashion Industries for next school year; at least two other schools are in talks as well. The partnerships would enable MESA to serve 100 students in their north Brooklyn campus next school year, in the heart of a large Latino community.

While a high school’s success is often sized up by its graduation rate, co-executive director and co-founder Pagee Cheung believes metrics from alumni’s post-secondary lives should serve as a wake up call.

“The goal is beyond just graduation numbers — how are they surviving once they leave?” said Cheung. “There’s a vacuum in accountability and responsibility.”

‘I’d still be lost’

Five years after graduating, Jackie, a young mother, sat intensely focused at a full table in her alma mater’s media library. She and Eduardo, who graduated in 2020 into an uncertain world, shared a table as they decided their top three work programs from a packet of options.

Without MESA, Eduardo said he’d be scouring the internet for programs that he felt met his interests, without much understanding of financial literacy or what made a high-quality program.

“It would be a waste of my time,” he told The 74.

And time is of the essence — his younger brother recently graduated from MESA as well; his younger siblings still have a few years left in school. He knows that this age is also when some peers start contributing to retirement.

“I want [my siblings] to chase what they want to do without restrictions,” said Eduardo, whose last name has been withheld for privacy. “With my financial stability, I might be able to help them get to theirs, and just create this long line of financial stability.”

Starting in 2023, participants were compensated $500 for attending two 90-minute workshops for six weeks.

“If they’re cutting back on their hours at Footlocker [to attend], that’s a hard ask,” Samuels explained. “Forgoing income in the short term might mean getting evicted or missing meals. Having the ability to offset some of that lost income through stipends made a huge difference.”

Beyond financial obstacles, there are often mental barriers that prevent young people from being able to participate in similar programs.

“For many of them, there’s this shame and guilt attached to not being where they should be or comparing themselves to others,” Cheung said.

Participants also described a sort of imposter syndrome when they are accepted into a workforce or degree program, that they’re not deserving of the opportunity.

“The conditioning has been, this probably isn’t going to work out for you anyway. When there is an obstacle, it confirms that thought process,” Samuels said, adding that they are encouraging a “mindset that I am entitled to have a career that is financially sustainable and personally satisfying. I can advocate for that and there are people who are able to help me.”

Creating a network of peers was essential: instead of individual counseling, MESA offers cohorts that go through workshops as a group.

In leading workshops, MESA teachers emphasize trial and error to counter the narrative that young people have to know exactly what they want to do by 20. A former student who wanted to become a firefighter, for example, was coached to try out a common exercise regimen, then decided he couldn’t sustain that for years.

When second cohort alum Luis Rodriguez first graduated alongside Eduardo in 2020, he followed the path he always imagined: pursuing college sports. But when the pandemic halted athletics and he didn’t feel the quality of education at Buffalo State was “as good as I thought it would be,” he left.

Rodriguez worked at various factories and warehouses in Pennsylvania and New York before he heard about MESA’s workshops from a friend. He didn’t hesitate to get involved, wanting to figure out a new path instead of working nonstop.

But it wasn’t until MESA’s alumni program presented culinary arts as a career possibility and a former coach pushed him that he seriously considered it.

“I just be in my head so much… What if I take this path and it doesn’t work out, then I have to start all over? It took me a while to realize that sometimes that’s just what happens. It’s not a bad thing,” he said.

MESA’s position as a high school that has kept strong relationships with alumni and their families for years makes it uniquely positioned to push participants when they start to doubt themselves, or advocate on their behalf.

In late April, Rodriguez finished his first shift at a Mexican fusion restaurant in Astoria, a new culinary placement through the Isaacs Center.

“I would still be at a warehouse job, honestly, if I didn’t find this workshop. And still be lost.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter