Teachers Unions Historically Supported Campus Cops. George Floyd’s Death — and a Wave of ‘Militant’ Educator Activists — Forced Them to Reconsider

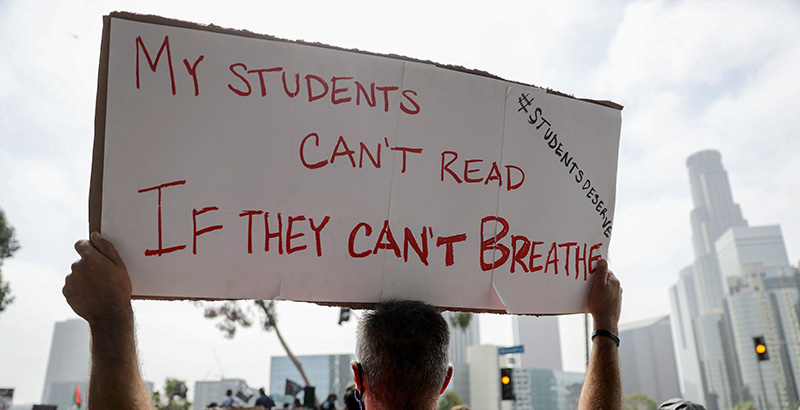

When Chicago educators hit the pavement last month with picket signs demanding police-free campuses, they challenged a security strategy that teachers unions have long embraced — and one that continues to divide school staff nationwide.

Chicago Teachers Union members marched to chants of “Counselors, not cops” while their president, Jesse Sharkey, logged into a virtual school board meeting and urged education leaders to terminate a $33 million contract with the city’s police department. The rationale often used to keep officers in schools, including claims that they are positive role models for students, has “racist underpinnings,” he told the board.

Sharkey’s comments reflect a substantial shift in the union’s rhetoric. Just a few years ago, then-President Karen Lewis drew controversy when she declared at a protest that the “cops are not our enemies” and stated her wish to reform, not dismantle, school policing.

After George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis police custody, teachers union leaders in Chicago and elsewhere joined youth activists and civil rights groups in calling for police-free schools. Student demands, which for years had fallen on deaf ears, are now getting a hearing, with districts from Portland, Oregon, to Milwaukee severing ties with police departments. In Chicago, the move fell just short: The school board voted 4-3 to maintain its contract.

Defunding school police, union leaders argue, would allow districts to invest more in services that could improve learning conditions for students, such as social workers and nurses.

“It’s not just, ‘Get cops out,’ it’s ‘Get cops out of schools and make sure schools reflect the needs of the students,’” Stacy Davis Gates, the Chicago union’s vice president, told The 74. Failing to respond to the demands of Black Lives Matter activists, she said, would “mean that we have a mask over our face and our ears plugged.”

The transition reflects a broader shift in public opinion. Following Floyd’s death, a majority of registered voters said they supported the Black Lives Matter movement for the first time. Meanwhile, the pandemic has brought an economic crisis for schools and communities, forging an urgency around reforms that could make schools more equitable for students of color and those from low-income households.

The change also reflects a shift within the unions themselves, where a crop of educator activists in Chicago and elsewhere have pushed teacher groups to support causes far beyond bread-and-butter issues like salary and class size.

“It’s not a coincidence” that teachers unions are calling for police-free schools in cities like Denver and Los Angeles, where raucous educator caucuses committed to social movements and anti-racism platforms have gained significant influence, said Jon Shelton, an associate professor of democracy and justice studies at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay. “They’re more militant; they’re willing to galvanize their members and go on strike,” such as in the recent “Red for Ed” protests demanding more money for schools. “And these unions have largely been winning,” he added.

In Madison, Wisconsin, the union previously supported school-based police in the city’s high schools. After Floyd’s death, it embraced students’ demands for change because “the benefits of having police officers stationed inside our schools is outweighed by the racialized trauma experienced by some of our community members of color,” the union said in a statement.

Yet recent educator surveys highlight a complicated relationship between teachers and police. Most educators nationwide support Black Lives Matter, according to a recent Education Week survey, but overwhelmingly oppose removing police from schools.

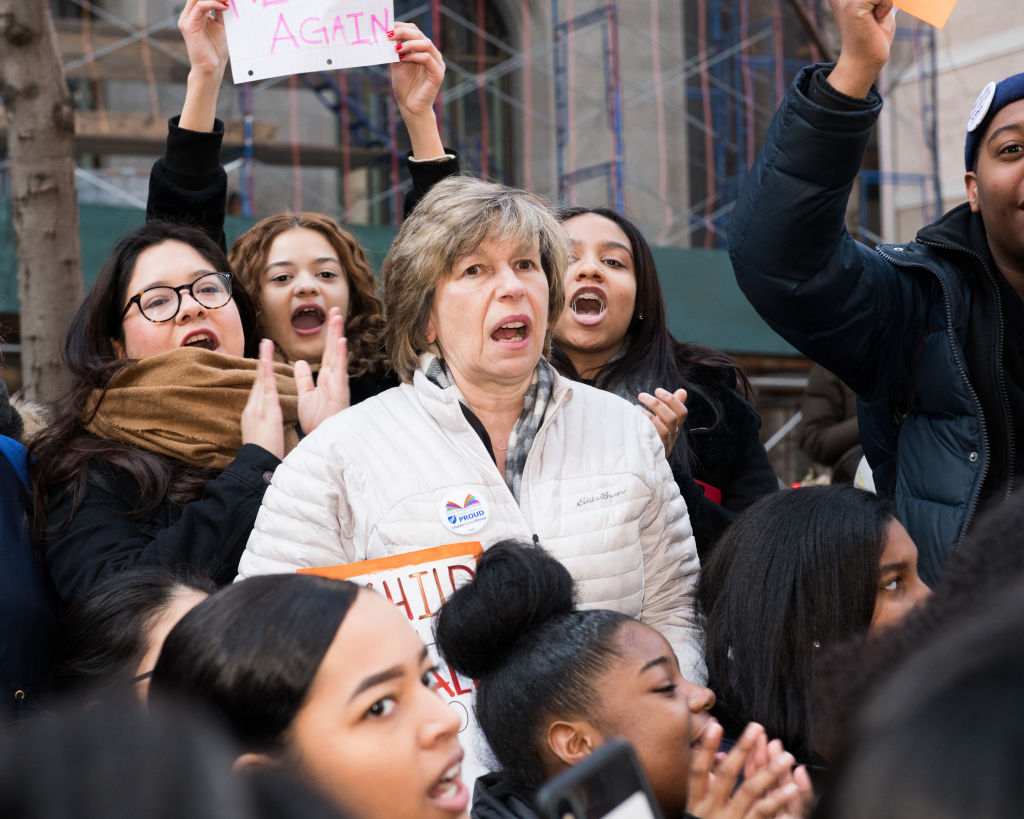

In an interview with The 74, Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said a recent survey of her members reached a more nuanced conclusion: Nearly three-quarters said they believe school safety efforts “should be separated from police” and that districts should have their own security officers focused on “nonviolent resolution of conflicts with a minimal use of force,” she said.

Weingarten also pushed back on youth protesters, noting that some degree of security in schools is necessary, so long as it’s “not a militaristic police state.” Ahead of the AFT’s national convention this week, Weingarten said its members will have a “unionwide conversation about what that looks like and what that means.”

“Whereas some of our students are saying, ‘We don’t need any security in the school whatsoever,’ many of their parents and teachers are saying, ‘Yes, we do,’” she said. “But there’s going to be a way that we can have this conversation and find solutions.”

Unionizing for social justice

For years, the Chicago union has promoted approaches to school discipline that are less punitive than suspensions and arrests. But the call for police-free schools is relatively recent, beginning with a 2014 incident in which a Chicago police officer killed 17-year-old Laquan McDonald. Video footage showed that the white officer, later convicted of murder, shot the Black teenager 16 times.

“Students of color have not received the schools that they deserve, so it’s a very natural and connected demand to say, ‘Our students have been over-policed and under-educated,’” said Jackson Potter, who founded the union’s Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators.

Under the caucus’s control, the Chicago union has placed a greater emphasis on improving school conditions for children of color, who make up roughly 90 percent of the city’s students. But the transition hasn’t always been smooth, Potter acknowledged. Delivering a speech during a 2016 strike, Lewis, the former union president, was sharply rebuked by protesters. Activists chanted, “Get cops out of schools,” but Lewis, who is Black, declared that police are not the enemy. Page May, a private-school teacher with the racial-justice group Assata’s Daughters, took the stage and responded, “Fuck the police, and everybody fucking with them.”

Potter, watching from the wings, said Lewis was walking a “complicated tightrope” between coalition-building with other activist groups and serving members’ interests.

“It did inhibit some of those relationships from developing that we are now kind of repairing,” Potter said of the incident. “Sometimes, you move two steps forward and one step backwards, but overall, I think we’ve been headed in the right direction.”

The Chicago union has served as a model for other cities. In San Antonio, the union has been “essentially supportive of school policing” but without offering a fully articulated position, said Luke Amphlett, a member of the educator group’s social justice caucus. Though the union has called on the district to follow a 2019 Texas law that prohibits schools from using police for routine student discipline, he’s pushed teachers there to take a more aggressive tack.

“This is definitely a hugely contested and controversial conversation here, and it is in union locals across the country,” he said. “We definitely don’t have homogeneity among the membership.”

Angela Harris, chair of Milwaukee’s Black Educators Caucus, has taken on a similar role in her city, where the school board recently voted to end its contract with the police department. The union soured on the district’s police contract after Floyd’s death, she said, but some educators vocally opposed the move.

When the caucus called for police-free schools, “people were very upset with me,” she said, including “people who I considered to be my professional counterparts — even friends.”

National reckoning

While battles raged locally, a quieter transformation has been afoot at the national level, where leaders have historically supported campus police, often called school resource officers.

In a letter to congressional leaders, the AFT and the National Education Association called on lawmakers to adopt criminal justice reforms to “protect Black communities from the systemic perils of over-policing,” but they’ve been far less vocal on the issue than many of their local affiliates.

The NEA, which didn’t respond to a request for comment, has supported officers in schools for more than a decade. A 2011 article in the union’s newsletter — titled “Promoting School Safety with a Badge and a Smile” — said police officers, surveillance cameras and metal detectors “are sometimes necessary” to ensure safe schools. It also backed federal efforts to bolster school policing after the 2012 mass school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut.

But in a recent exit interview with Education Week, outgoing NEA president Lily Eskelsen García said she has “grave concerns about armed police officers in schools.”

Just two years ago, after the 2018 mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida, Weingarten touted police as a viable school safety strategy at a time when the Trump administration advocated arming teachers. A 2019 plan on preventing mass school shootings from the AFT, NEA and the group Everytown for Gun Safety said stationing police in schools “is a decision that must be made on the local level.”

Following Floyd’s death, the union’s executive council adopted a resolution calling for school safety efforts to be “separated from policing and police forces.”

For Amphlett of San Antonio, the resolution is a sign of progress. Separating policing from school safety “is basically coded language that we need to end school policing as we understand it at the moment,” he said. But he called AFT’s inability to explicitly call for police-free schools a “cop-out.”

‘Force for good’

One explanation for the distance between the national unions and their local affiliates is offered by the recent Education Week survey.

It found that just 23 percent of educators supported removing armed officers from schools, and 54 percent said campus police are needed in their districts.

Black students are disproportionately arrested at school compared with their white peers, yet the majority of educators said school officers treat students of color fairly, and just a quarter said they contribute to a “school-to-prison pipeline.” Despite a dearth of research showing that officers are able to mitigate bloodshed during mass school shootings, such tragedies drive educators’ support for officers, according to the survey.

Some educators have argued that police-free schools put an unreasonable burden on educators. That’s the view of Philadelphia teacher Quinn O’Callaghan, who said in a recent op-ed that he isn’t trained or emotionally prepared “to fulfill the role of safety officer.”

“Additionally, to ask school teachers to assume the responsibilities of a law officer is shifting a remarkable amount of labor onto teachers, who are already at the center of an overstressed, undersupported system,” he wrote.

Educator support for school police can also be found in Pittsburgh, where the local union has fought against a push to remove officers from campuses.

After a Pittsburgh Federation of Teachers member survey found that 96 percent of city educators oppose removing police from schools, union president Nina Esposito-Visgitis told the school board it’s “wrongheaded” to terminate officers who are “problem-solvers, risk managers and an overwhelming force for good.”

Back in Chicago, the debate over campus cops continues despite the school board’s vote to retain its contract with the police department. In fact, Potter called the board’s split vote monumental. Mayor Lori Lightfoot, who said police are necessary in schools, appointed all of the board members.

“I don’t know of a Board of Education vote that went down 4-3 in the history of the board,” Potter said. “What we are seeing is a historic break from tradition, that even an appointed school board of Lori’s own creation is feeling the pressure.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter