Los Angeles Schools Regain Control of Special Education After More Than 20 Years. What That Means for Priorities, Parent Concerns in the Nation’s Second-Largest District

This month marks a notable milestone for L.A. Unified: For the first time in more than two decades, it’s now in full control of its special education system.

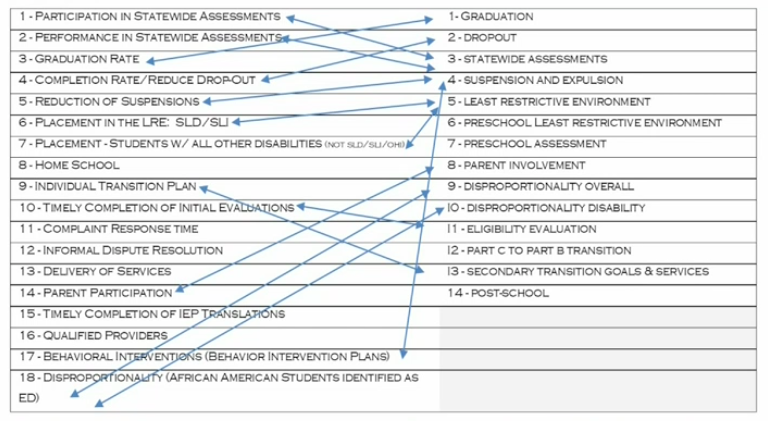

Until this month, the nation’s second-largest school district had unique court-ordered mandates to improve and expand services for its nearly 62,000 special education students, stemming from a 1996 legal settlement. In 2003, the agreement was modified to include a third-party “independent monitor,” who meticulously reviewed and published annual reports on L.A. Unified’s compliance in 18 areas — such as whether students with disabilities receive all of the services mandated in their Individualized Education Programs and how often they were subject to out-of-school suspensions.

The so-called consent decree governing special education formally ended Dec. 31, following an agreement reached in August with the lawsuit’s original plaintiffs. For district officials and some disability advocates, the decision is recognition of having met “nearly all” of the consent decree’s mandates. Officials added that there’s now flexibility to shift L.A. Unified’s focus to working on its compliance with the state’s special ed performance targets, and to continue building local-level supports that cater to “the individual needs of our students.”

“The most exciting part about this is this chapter of our work will be guided by educators and parents rather than lawyers,” Superintendent Austin Beutner said Wednesday. He added that the district is “not leaving compliance behind, because that’s a big part of the work.”

Although there is optimism from some parents that the decree’s end will spur fresh conversations about how to best serve students with disabilities, it remains unclear for many how the district intends to hold itself accountable for serving these students, who make up 13.6 percent of L.A. Unified’s enrollment.

“Parents are deeply worried that when the oversight is lost, it will be that much harder for students with special needs to achieve success in LAUSD,” one parent told the school board’s special education committee in September.

There is still work to be done, as independent monitor David Rostetter wrote in his final Dec. 13 report. Thousands of special education students are reportedly receiving less than 70 percent of their required services. Many of L.A. Unified’s more than 1,100 district schools remain out of compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, with about 1 in 5 lacking an accessible main entrance. And academic outcomes for students with disabilities are trailing statewide averages: In 2018-19, 11.81 percent of all L.A. Unified students with disabilities met or exceeded state English standards, while 9.41 percent met or exceeded them in math. State averages for this group, comparatively, were 16.26 percent and 12.61 percent.

Higher standards for these students — and more expansive teacher trainings — would ensure that those “closest to students with special needs have the information and support they need and can work together to better serve these kids,” said Lisa Mosko, a mother of two children with learning disabilities and Speak UP’s director of special education advocacy. “We need to raise the bar.”

Progress and a change in focus

While L.A. Unified struggled to check certain boxes under the consent decree, the independent monitor’s report acknowledges marked progress in several areas:

- The percentage of students with disabilities receiving out-of-school suspensions was at its lowest ever in 2019 — 1.1 percent, compared with 14.1 percent during the 2004-05 school year. The report credits this in part to L.A. Unified’s decision to ban willful defiance suspensions in 2013.

- About 60 percent of students with mild to moderate disabilities are currently spending the majority of their day in general education classes, a percentage district officials note has been “steadily increasing.” (Some parents dispute whether inclusion in general ed is always beneficial.)

- The district is fulfilling 99.9 percent of the requests it receives to translate students’ IEPs into a language other than English within 30 days — up from 8 percent at the start of the decree. Nearly 22 percent of students are English learners.

- The district has seen “tremendous success” in combating implicit bias in special ed evaluations. As of 2019, 92.5 percent of black students classified as “emotionally disturbed” met the legal criteria for that special ed identification. In 2004-05, it was only 2.7 percent, according to Disability Rights California.

“LAUSD has come an incredibly long way,” David German, an attorney who represented the advocates and parents who sued, told Speak UP. Ending the consent decree “means they’re complying with their obligations under federal law. They got up to the baseline, which was a big deal.”

L.A. Unified had been one of the few districts in California held to a special education consent decree.

Moving forward, L.A. Unified is “intensify[ing] its efforts” to meet and track its compliance with 14 state performance indicators, a district spokeswoman said — many of which overlap with the now-retired consent decree requirements. L.A. Unified is not on-target with about half of the state’s performance indicators, according to data shown in a Sept. 19 committee presentation.

Beutner was hesitant to detail specific ways the district’s priorities are shifting, saying that “each of these [state] measures are somewhat narrow; [the district is] looking at the bigger picture.” He and other officials did note that a central focus continues to be placing more students with disabilities in the least restrictive learning environment, alongside peers in general ed classes.

“We are making a big push as a school district to put all of our resources closer to schools and the communities they serve,” Beutner said.

It’s not yet known how much money L.A. Unified will get from the state in 2020-21; Gov. Gavin Newsom unveiled his latest budget proposal this month, earmarking nearly $900 million in services for students with disabilities. L.A. Unified in 2019-20 budgeted about $1 billion of its nearly $8 billion general fund for special education.

As the district transitions, Mosko has stressed her disenchantment with the state’s special education standards to officials. They’re subpar, she says, considering research showing that 80 to 85 percent of special education students can “meet the same achievement standards as other students if they are given specially designed instruction” and supports. The state’s academic goals as of 2018-19 were for 15.9 percent or more of students with disabilities to be proficient in English and at least 13.6 percent to be proficient in math.

“I would like to see a more aggressive stance [by the district] in terms of, ‘We should be at 80 percent. How do we get there?’” she said. “I want to see more urgency.”

Anthony Aguilar, chief of Special Education, Equity and Access, confirmed Wednesday that the district is “taking an extra look at our academic achievement … Even though we’ve made some positive gains, we recognize that we need to accelerate.”

District 3 board member Scott Schmerelson, who chairs the board’s special ed committee, said he “absolutely” supports the district’s choice to home in on compliance with state indicators. Although he initially questioned whether the district had “the systems in place, the people in place” post-consent decree to continue prioritizing obligations like fulfilling students’ IEPs, his concerns were assuaged after discussions with district officials, he said.

“I’m very confident that we will continue to monitor all of these services,” he said.

Accountability moving forward

Parents seemed less confident at another public hearing in September, where they expressed fears about the loss of the independent monitor.

“My concern is once oversight is removed … the schools have implicit bias to protect themselves from liability, to protect their general funding,” one parent said. “They are also on time constraints, so that they cannot take the time to hear my concerns day in and day out.”

The independent monitor hosted hearings like these for community members twice a year and published public, yearly reports, often chock-full of data and upwards of 40 pages long. When asked if L.A. Unified will continue both of those practices, Beutner said the district “intends to continue to share information on progress toward all goals” and to host public forums in the local communities as well as in the central offices.

Pulling from current staff, L.A. Unified also recently assembled a 17-person Compliance and Performance Monitoring Legal Services department to help “oversee internal monitoring processes to ensure that programs and services operate in a manner that promotes program accessibility, equity and compliance,” the district spokeswoman said.

Funds that had been paying for external oversight will be “available to support the internal oversight” of special ed services, she added. There have been discrepancies on the cost of the oversight: Beutner in an interview with the Los Angeles Times last summer estimated $3 million to $5 million a year. The independent monitor put the cost in recent years at “less than $800,000 on average.”

Looking at the state’s special education indicators, they don’t appear to address some areas where the independent monitor said L.A. Unified needs continued work. A few examples, with the district’s responses:

- A decline in the number of qualified providers. The percentage of special ed teachers with a special education credential has been decreasing since 2013-14, from 96.4 percent that year to 84.9 percent as of June 2019. The district didn’t offer any plans to remediate this, stating that “the issue of qualified teachers is one of statewide and perhaps national concern … due to factors such as retirements and declining number of teachers entering the workforce.”

- Accessibility. Making schools accessible to all students has been “one of the least successful parts of reform” to L.A. Unified’s special ed system, the report states. While the school board in 2017 passed a three-phase plan to make all schools accessible, the report notes that the first phase alone runs through 2025 and reportedly requires an extra $1 billion on top of the $600 million the board allocated.

The district emphasized that accessibility and “ADA-related goals” will be a continued focus, in accordance with federal law.

Schmerelson said board members will “make sure that our legal department is following through on any complaints that parents may have about services being received or not received, and acting on it immediately.”

He believes that “everything should be done at the school site.” Local district superintendents, their special education administrators and school principals especially, he said, should be overseeing whether students receive all of their required services and working to remediate parents’ complaints in lieu of legal action.

Parents with complaints are urged to use their principal as “the first point of contact,” the district spokeswoman said. She noted that the Division of Special Education also fields concerns and complaints through its call center and Complaint Response Unit. Parents can use the California Department of Education’s complaint process as well.

Mosko, the parent and Speak UP advocate, said the Division of Special Education has been “very responsive when I request information.” She said she’s been “heartened” by recent leadership there and that “they seem to be prioritizing transparency of information more.”

Mosko said she will continue to advocate, especially on the “systemic issue” of not enough teachers being trained to properly serve students with disabilities. The California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, she noted, doesn’t require special education teachers to know federal law as it pertains to students’ IEPs. And general education teachers, at most, might take one or two “very general courses” on special ed.

The district has increased funding to provide for more professional development opportunities, Beutner said. Specific amounts can’t be shared until district schools are given their initial budgets in mid-February.

Ultimately, it’s “a bottom-up transformation” that will make all the difference, Mosko said. “If people on the ground don’t have the information and the training and the knowledge … all you get is a bunch of lawsuits and a bunch of kids lost in the system.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter