Uvalde School Police Chief Placed on Leave

Schools superintendent takes action nearly a month after shooting as criticism of Chief Arredondo’s actions intensifies

Updated, June 22

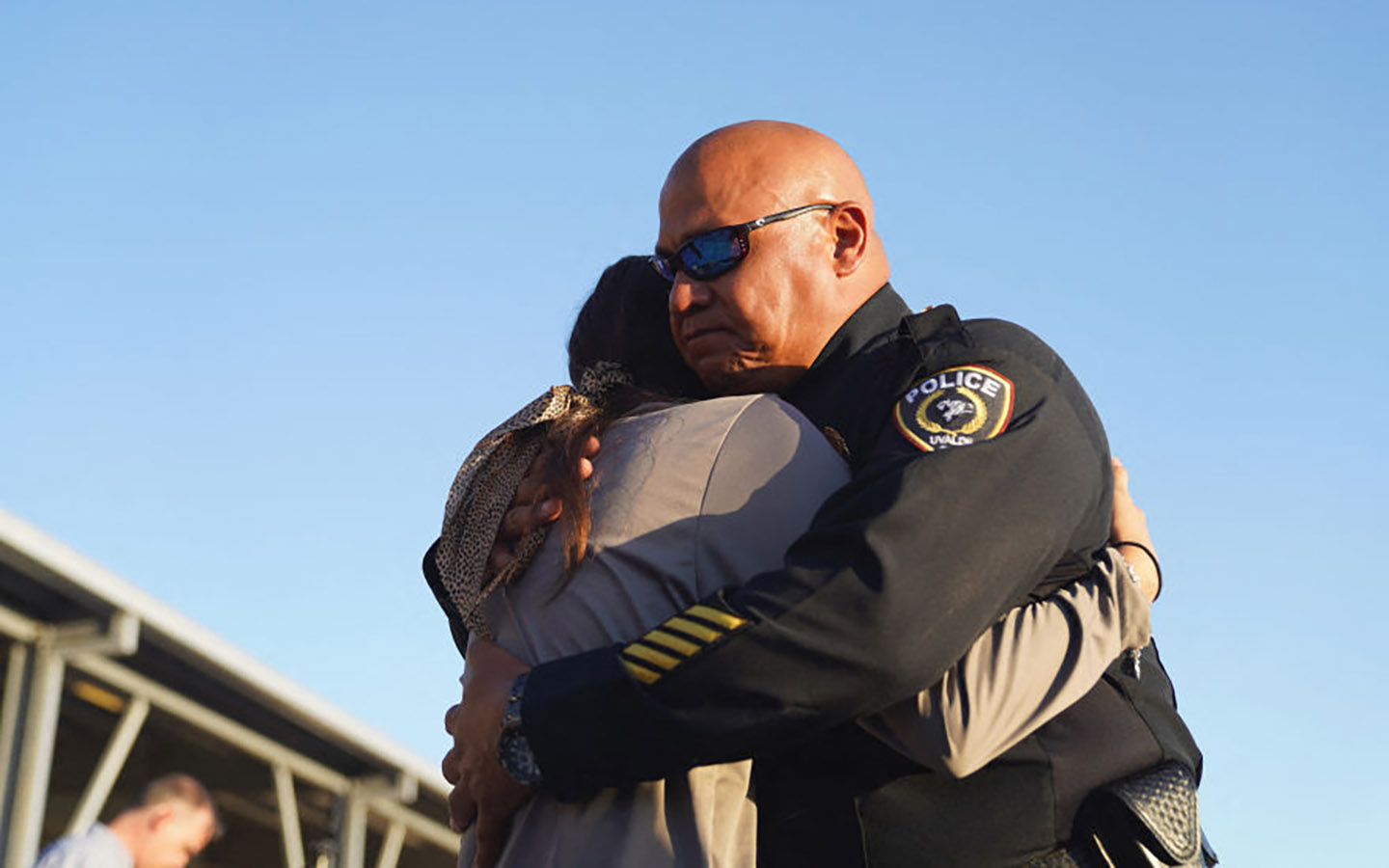

Uvalde school district Police Chief Pete Arredondo was placed on administrative leave Wednesday, schools Superintendent Hal Harrell announced in a brief written statement. The move came after Steven McCraw, the director of the state Department of Public Safety, told state lawmakers Tuesday that Arredondo’s decision to wait more than an hour to confront the gunman during a May 24 mass shooting at Robb Elementary School “put the lives of officers ahead of the lives of children.” Two teachers and 19 students died in the attack, which is now under investigation by multiple agencies. Harrell said it was the district’s intention to wait until those investigations were complete before making any personnel decisions. But because of “the lack of clarity that remains and the unknown timing of when I will receive the results of the investigations,” the schools chief said he decided to place Arredondo on leave effective Wednesday. A lieutenant in the six-member department will take over. The Texas Tribune reported that a district spokeswoman would not confirm if the leave was paid or unpaid.

Police and school security experts are questioning why the Uvalde, Texas, school police chief remains on the job nearly a month after a gunman killed 19 children and two teachers at the local elementary school.

While Chief Pete Arrendondo’s fiercest critics have demanded he be fired following reports that officers under his command waited more than an hour before confronting the shooter, school safety and police accountability experts criticized education leaders for failing to remove him as head of the six-member school police force, even temporarily.

Placing cops on “paid administrative leave or in a no-contact assignment” after an officer-involved shooting is standard procedure, according to the world’s largest professional trade group for police chiefs. Those standards, experts told The 74, are critical to the public’s confidence in the ensuing investigations, the school community’s safety and even the chief’s well-being.

“It’s just baffling that you would have this conversation days after the incident, much less weeks or a month out,” said school safety consultant Kenneth Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Services. Trump said the standards for officer-involved shootings should apply to Arredondo, a nearly 30-year law enforcement veteran whose response to the Robb Elementary School mass shooting is the subject of investigations by the local district attorney’s office, state law enforcement and elected officials and the U.S. Department of Justice that will likely take months.

Investigators will scrutinize why officers waited outside a classroom door for more than an hour despite frantic 911 calls from the children inside begging for police to save them and reports that there were others trapped with the gunman who were injured but still alive. Eventually, Border Patrol agents and other law enforcement stormed in and killed the shooter. Arredondo, who was identified as the incident commander on the scene, reportedly made the call not to go in immediately.

Steven McCraw, the director of the state Department of Public Safety, on Tuesday called the police response an “abject failure,” and said the classroom door was apparently unlocked despite the cops’ decision to wait for a key before entering the room to confront the gunman. Just minutes after the first shots were fired, he said, the police had enough firepower and protection to act.

“The only thing stopping a hallway of dedicated officers from entering Room 111 and 112 was the on-scene commander,” McCraw told Texas state lawmakers. Instead, Arredondo “decided to put the lives of officers ahead of the lives of children.”

Before those statements, Trump said that Arredondo should be taken out of his leadership role with the school district.

“If there indeed is something found where he made some fatal errors in his decision making, then you don’t want that person still there making decisions on that or other situations,” Trump said. Arredondo witnessed one of the deadliest mass school shootings in U.S. history, a traumatic event that Trump said could cloud the chief’s decisions. “Why would you put somebody under that duress — whether they’re consciously aware of it now or at a later point in time — in a position where they could encounter another stressful or life-threatening situation?”

Arredondo’s position at the police department’s helm remains uncertain as he avoids public appearances and Uvalde district officials refuse to detail his employment status. But evidence suggests he’s taken on additional responsibilities since the May 24 shooting, with his attorney telling The Texas Tribune that the chief has picked up extra shifts to cover for grieving officers. The Texas Rangers had asked Arredondo to participate in an interview for their investigation into the immediate police response, attorney George Hyde told the news outlet, but he was too busy filling in for his officers.

Arredondo also made time to go to City Hall and be sworn in as a newly elected Uvalde city councilmember a week after the mass shooting. The New York Times reported that the Uvalde City Council voted Tuesday not to offer Arredondo a leave of absence. The chief has not attended meetings since his swearing-in, its story said, and could be forced to give up his seat after missing three meetings.

The Uvalde school board at its first meeting since the armed assault, considered whether to reassign or fire Arredondo, but after a closed-door discussion chose not to take immediate action. Board members and a district spokesperson didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The law firm representing Arredondo said he declined to comment for this article, but the 50-year-old police chief defended the police response in his extensive June 9 interview with The Texas Tribune. Arrendondo pushed back against statements that he was the incident commander, saying he did not consider himself to be in charge of the scene and did not give orders to other responding officers, including holding off cops who were impatient to breach the door.

“Not a single responding officer ever hesitated, even for a moment, to put themselves at risk to save the children,” Arredondo told the nonprofit news outlet, though his comments appear to contradict video evidence obtained by The New York Times and later the Tribune itself. “We responded to the information that we had and had to adjust to whatever we faced. Our objective was to save as many lives as we could.”

McCraw reiterated Tuesday that Arredondo had assumed the role of on-site commander by issuing orders and directing action.

‘He really failed’

Since the horrific shooting, Trump and other school security experts have been highly critical of officers’ decision to wait in the hallway. For decades, law enforcement has been trained to confront the gunman — even at the cost of their own lives.

Such standards grew out of the 1999 mass school shooting at Columbine High School in suburban Denver, with a realization that every second counts during a mass shooting, most of which are carried out in a matter of minutes. A more aggressive response at Uvalde, experts argue, could have saved lives, perhaps including one teacher who reportedly died in an ambulance and three children who passed away at nearby hospitals.

Public information about Arredondo’s actions that day — and his own admissions that he ran into the school without his police radio or quick access to the key he said was necessary — raise significant questions about his ability to perform his job, said Samuel Walker, a national expert on police misconduct and professor emeritus of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Those questions, he said, necessitate action as investigators examine his conduct.

“It appears that his actions were not appropriate and it’s entirely appropriate that he be on leave,” Walker said. “Unless some new evidence comes to light, it looks like he really failed in his responsibility and I think that disqualifies him from working any job in that school district.”

Sheldon Greenberg, an education professor at Johns Hopkins University and a former police officer, said that disciplinary procedures for cops vary greatly across the country and officers often benefit from policies and labor contracts that protect them from facing repercussions for failures on the job.

Several factors complicate this particular situation, Greenberg said. For one, as chief, Arredondo would typically make disciplinary decisions for officers in his department. In the case of the chief, that responsibility would fall to the district superintendent and the school board, who may have little to no experience in police disciplinary matters, Greenberg said. Additionally, he said it’s notably difficult to hold an officer accountable for failures to perform job duties.

“There’s a difference between a police officer who commits an act,” like the Minneapolis police officer who murdered George Floyd “where the officer had his knee on his neck and was forcing compression on his neck for nine minutes,” Greenberg said. With Arredondo, “what he did you might categorize as omission, which is very different.”

Officers at the 4,100-student Uvalde school district, including Arredondo, had been trained as recently as last year on how to respond to an active shooting, and materials by the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement urge cops to “Display uncommon acts of courage to save the innocent.”

“As first responders we must recognize that innocent life must be defended,” according to the state training materials. “A first responder unwilling to place the lives of the innocent above their own safety should consider another career field.”

Despite the hardline language in the training materials, Greenberg said an officer isn’t helpful during an emergency if they get killed.

“You can’t do much if you’re dead or disabled,” he said. “You still go in with reasonable caution, just don’t go barging into a room unless you’re sure you have a genuine opportunity to stop the gunman.”

Trump, the school safety consultant, said that placing Arredondo or any officer on administrative leave shouldn’t necessarily be framed as a disciplinary measure. While Arredondo’s continued role in the department could raise concerns about obstruction in the active investigations and about his capacity to keep the community safe, he said that any officer who responded to the elementary school should have a chance to go on leave to recover from the traumatic event.

In many police departments, he said the move is routine procedure, yet it’s unclear what policies are in place for the school district’s six-person police force. A policy manual for the Uvalde school board notes that the police chief “shall be accountable to the superintendent,” but a review of the rules did not yield any insight on leave of absences. Arredondo and any other officers who are placed on leave should continue to receive a paycheck, Trump said.

“They shouldn’t have to worry about income for their family, but they should have that paid leave for them to debrief, to decompress, to process, to not be exposed to continual trauma,” Trump said. While any police-involved shooting can cause distress for the officers involved, the Uvalde shooting resulted in the deaths of 19 children. “They’ve been exposed to major trauma and stress of the worst kind.”

Trump was less sympathetic to Arredondo’s assertion that he’s been too busy to participate in interviews with investigators. Making himself available for questioning, he said, should be the chief’s number one priority. In fact, it’s another reason to put Arredondo on leave: To ensure he has the time and flexibility to cooperate. Meanwhile, officers from outside police departments across the state responded to Uvalde to help.

“I can’t think of anything that anybody should or could be doing that would make them too busy to participate in an investigation into a major school shooting like this,” Trump said. “It’s among the biggest and the worst [mass shootings] that we’ve ever had. That answer certainly doesn’t carry water with most anybody, including the school community.”

‘Coward of Broward’

Arredondo is not the first school-based police officer to face scorn for his performance during a deadly crisis. School resource officer Scot Peterson was placed on administrative leave in 2018 for failing to confront the gunman at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

Peterson ultimately chose to retire and was subsequently charged with seven criminal counts of child neglect. Prosecutors said he took cover behind a wall while the gunman killed 17 people. Those actions earned him the nickname the “Coward of Broward” by ardent critics in his Florida county. Even his boss, then-Sheriff Scott Israel, said at the time that Peterson’s actions made him “sick to my stomach.”

But Peterson has framed the steps taken against him as a “political lynching.” His attorney, Mark Eiglarsh, told The 74 this week that with both his client and the Uvalde school police chief, “The court of public opinion is unfortunately so quick to condemn responding officers and the incident commander without knowing all the facts.”

“Unfortunately, due to the unprecedented and irresponsible decision” by prosecutors to charge Peterson, he said in an email, he fears that other officers, including Arredondo, “may also be stripped of their liberty and face decades in prison solely because a finding is made after the fact that things could have been handled differently.”

The case against Peterson is expected to head to trial in September.

Despite the numerous investigations into the Uvalde shooting, the accountability that many in this small Texas community are demanding may never come, according to legal experts. Qualified immunity, which protects cops from liability for their mistakes on the job, could challenge civil lawsuits. Meanwhile, charges against police officers — like the ones against Peterson — are extremely rare. But Walker, the police misconduct expert, expects the federal investigation to uncover failures in Uvalde that could help districts nationwide respond to similar attacks moving forward.

“It looks like he failed, and if you fail and cause the death of a number of children, then it’s pretty serious,” Walker said. Yet such shortcomings likely extend beyond Arredondo, he said, and it’s important that the chief doesn’t become the scapegoat. “Clearly there’s what we would call systemic failure, and the school board probably failed in some respects” if it lacked sufficient policies to respond to such a lethal event.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter