On a Per-Student Basis, School Staffing Levels Are Hitting All-Time Highs

Aldeman: Schools in 46 states effectively lowered their teacher-student ratios by continuing to hire while enrollment has dropped

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It’s a weird time to be having a national conversation about teacher shortages. Thanks in part to the surge of federal relief funds, schools have ambitious hiring plans — but they have been unable to bring on as many people as they would like. As of last month, job openings remain elevated well above normal levels.

And yet, on a per-student basis, schools today employ more teachers and other staff than they’ve ever had.

This may sound surprising or counterintuitive, so let’s use data on my home state of Virginia as an example. In 2018-19, the last full year before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Virginia public schools employed just under 87,000 teachers. In 2020-21, those same schools employed about 75 more, a gain of 0.1%.

That may not sound like much, but Virginia’s public school enrollment declined by 2.9% over the same time period. By dividing the number of students by the number of teachers, it becomes clear that Virginia districts were able to shrink their student-teacher ratio from 14.8 to 14.4.

These trends continued last year: Virginia schools added more teachers even as student enrollment continued to decline.

Virginia is typical of the rest of the country. Full data isn’t yet available for two states, Illinois and Utah, but of the remaining 48 states and the District of Columbia, almost three-quarters (36) added teachers in the first full year of the pandemic. Only two states, North and South Dakota, and D.C. served more students. As a result, schools in 46 out of 49 states effectively lowered their teacher-student ratios during the height of the pandemic.

Data isn’t complete for the 2021-22 school year, but I looked at 10 large states and found that all of them increased their teacher counts last year, even as student enrollment continued to lag behind pre-pandemic levels.

These are statewide figures, and some schools and districts are surely exceptions. These are also large-scale numbers, and it’s possible there are too few teachers in certain areas (like special education or STEM subjects) and too many in others. That mismatch may be especially acute in schools experiencing the most dramatic enrollment losses.

The same trends appear when broadening the approach to count all school district staff, not just teachers. Nationally, districts had slightly fewer employees in the 2020-21 school year, but student enrollment fell faster. That is, the number of school staff per student served continued to rise.

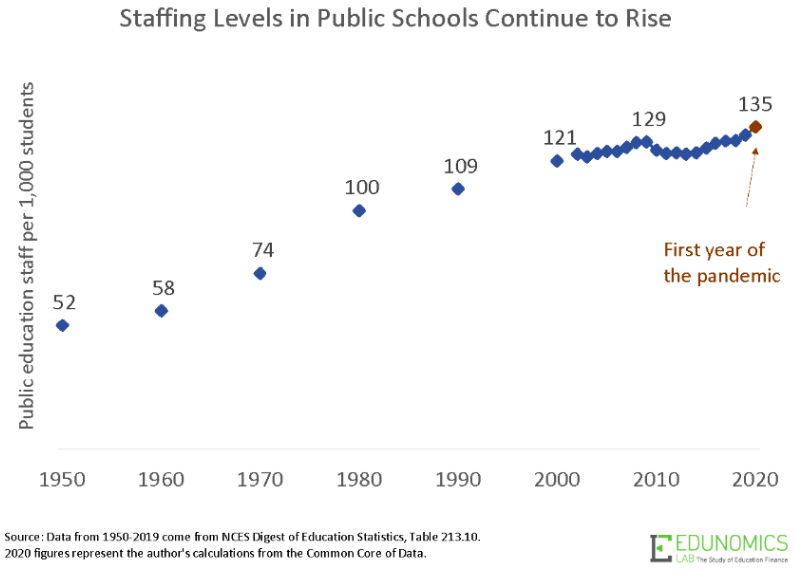

This continues the long-term trend. When the first Baby Boomers started attending public schools in the 1950s, a typical American school district employed about 58 workers for every 1,000 students enrolled. By the time Millennials like myself attended school in the 1990s, schools employed twice as many adults to serve the same number of students.

In the 2020-21 school year, staffing levels hit all-time highs, and the typical public school district employed 135 people for every 1,000 students it served.

Given the current rush to hire, I would not be surprised to see these numbers go even higher in the years to come.

These findings may raise some eyebrows. After all, as of the latest national figures, local public schools employ about 4% fewer people than they did in February 2020. But those statistics are misleading, because they include part-time staff. Other survey data suggest that nearly all the job losses in education came from part-time workers. The figures in the chart above use a different calculation known as full-time equivalents. Head count numbers might be germane in certain instances, but the number of equivalents better represents total staff time available.

My Edunomics Lab colleague Marguerite Roza has called adding staff the main “big bet” public education has pursued over the last 50 years. When school spending has risen, districts haven’t added more instructional time for students or raised teacher salaries. Instead, they’ve always increased staff.

Schools today employ many more teachers per student than they did in prior eras, across all subjects and grade levels, including art, music and foreign languages. But over the last decade, most of the staffing increases have come from non-teaching roles. Schools employ more counselors and specialists, like reading coaches; more instructional aides, to work with English learners and students with disabilities; and more vice principals and administrators, to oversee new regulatory and managerial tasks.

The investments in staffing increases have also come at the expense of investing in dedicated tutoring for students who are behind, or new ways to use and assign staff within schools. Those strategies might have helped with disruptions like COVID-19, but schools haven’t pursued those ideas at scale either.

Now that districts are flush with cash thanks to the infusion of federal dollars, they’re once again making a big bet on staffing. Unfortunately, old habits die hard.

This article was written and published while the author was with Edunomics Lab at McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter