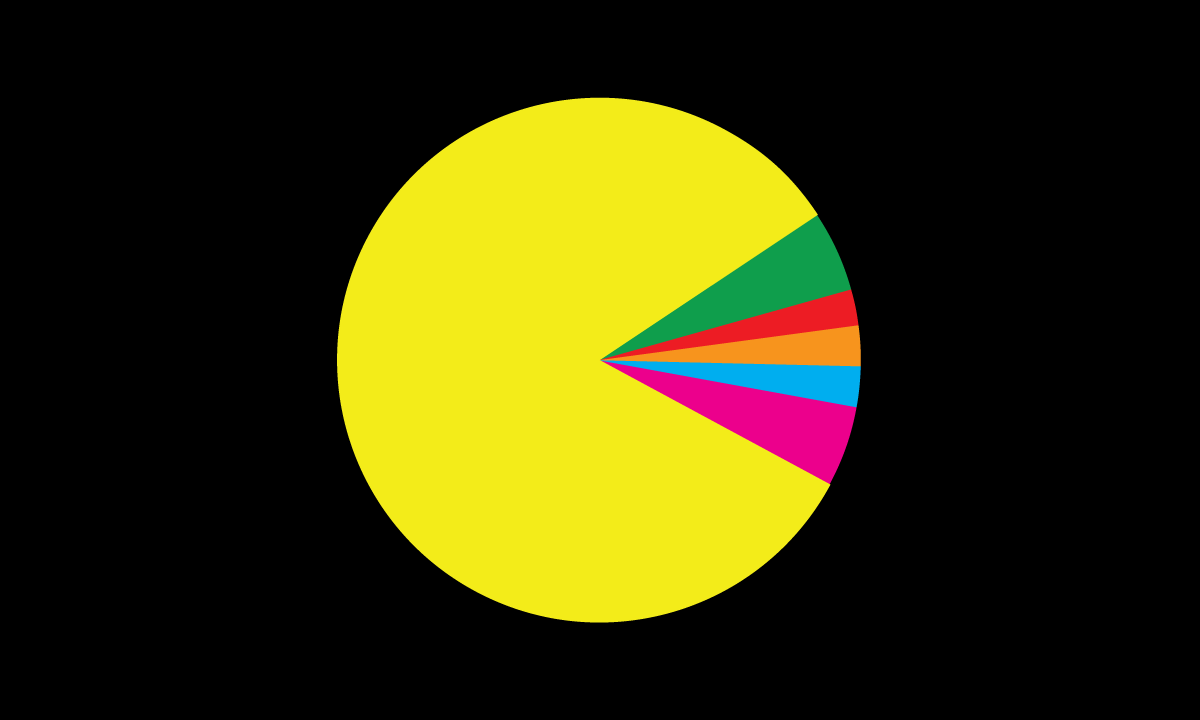

Teacher Pension Pac-Man: How Rising Costs Are Eating Away at Education Budgets

Aldeman: New report shows states and school districts are spending more on worker retirement plans — but those employees are getting less in benefits

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Unless policymakers stop it, the Teacher Pension Pac-Man will devour everything in its path.

A new report from the Equable Institute shows that rising pension costs are slowly eating up a larger and larger share of education budgets. After adjusting for inflation, teacher pension costs have roughly tripled over the last two decades, rising from $21.8 billion in 2001 to $63.7 billion in 2021.

Those increased costs have not led to better benefits for teachers and other school district employees. In fact, states have been systematically reducing the value of their benefits in response to the rising costs.

The chart below helps explain this growing disconnect. The light blue dotted line shows what pension actuaries call the employer normal cost, the estimated cost of the retirement benefits workers earn in a given year. It’s gone down a bit over time, reflecting a slow phase-in of benefit cuts for new workers.

In contrast, the red dotted line shows the pension debt costs, the amount of money that needs to be paid in order to address any shortfalls accumulated in prior years. As the chart shows, all the growth in pension costs over the last two decades has come from these debt payments. In other words, states and school districts are spending more on worker retirement plans, but workers are getting less in benefits.

The story of this growing disconnect has been told before, by myself and others. But the new Equable report has three unique contributions.

One, its analysts took the next step and put pension costs into perspective alongside broader education budgets. Pensions still represent just a fraction of overall education spending, but because pension costs are rising so much faster than everything else, that means true education spending is not growing as fast as it appears. Equable dubs these “America’s Hidden Education Funding Cuts.”

The authors leave it for us to imagine what schools might be able to do with an extra $44 billion, the amount that’s currently being siphoned away for the pension debt costs. By my back-of-the-envelope math, that money could raise the average teacher salary by almost $14,000 per year, or be used to hire 600,000 full-time instructional aides.

Two, the Equable report digs into the root causes behind the pension debts. Pensions are essentially promises to workers about the benefits they’ll receive in the future. In order to pay for those promises, states have to estimate how many workers will qualify for benefits, how much those benefits will be worth and how much employers need to save today in order to afford the payments.

There are a lot of potential errors in these estimates. For example, people are living longer and collecting pension payments for more years. But it turns out that states are mostly adjusting to those realities with only small financial hits.

Instead, by far the biggest factor in the build-up of the pension debts comes from overly optimistic investment assumptions. After all, if states can assume their investments will grow quickly, they don’t need to contribute as much along the way. But the numbers at stake are massive, and setting unreasonably high investment targets is the main culprit behind why states have amassed $816 billion in pension debts.

Third, Equable found large differences across states. Kentucky, New Jersey, Connecticut and especially Illinois and Pennsylvania have suffered the largest hidden funding cuts. In these states, education budgets are rising, but pension costs are eating up a larger and larger share of the money.

Meanwhile, Wyoming, South Dakota, Delaware, Nebraska and Florida have all done a comparatively good job of managing the growth of pension costs. So what can other states learn from them?

The biggest lesson, by far, is to set more reasonable investment return targets. States have an incentive to be overly aggressive in their assumptions, because that makes it look like they don’t need to contribute as much along the way. But that approach obscures the real costs and forces plan managers to seek out riskier investments. Lowering the assumed rate of return would cause some short-term pain as budget makers faced up to the true costs, but over time it would help plans get back onto sound financial footing.

Next, state leaders should stop putting the pension debt burden on school districts. Right now, state leaders might think they’re increasing education budgets even as they turn around and raise the contribution rates that school districts must pay toward the pension debt. That’s not fair. If state leaders created the pension debts, it should be the state that pays for them.

State budgets have seen a surge in revenue over the last couple years, and it would’ve been a good idea for states to use the opportunity to get their pensions in better financial shape. That largely didn’t happen. But the longer state leaders wait, the more the Pension Pac-Man will keep eating away at their investments in schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter