When COVID-19 and Economic Fallout Put Millions of Kids in Unsafe Places, Communities in Schools Went In After Them

By Bekah McNeel | May 27, 2020

Updated, May 28

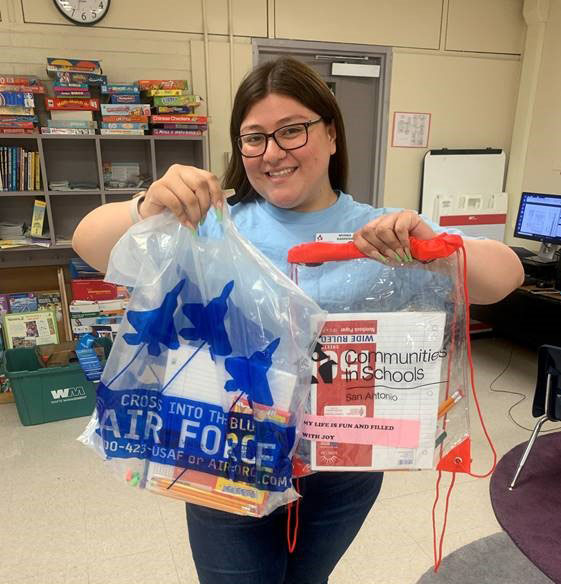

In some ways, Gladys Gradilla’s days are the same as they were two months ago, before COVID-19 shut down San Antonio. As the field manager for Communities in Schools, a national dropout prevention organization, in the South San Antonio Independent School District, she’s hearing many of the same needs she’s been hearing for decades. Food. Hygiene products. Academic help. Social and emotional support.

Only now, Gradilla said, coronavirus has schools locked down, supply chains stretched thin, and families sheltering behind closed doors, and all of those things are harder to get. Harder to deliver.

Needs have multiplied over the months as well. Early in the shutdown, she and her team spent a lot of time helping parents troubleshoot “the basics of access” as their kids tried to log on for virtual classrooms and online assignments. Communities in Schools staff have taken their help on the road, printing out instructional packets provided by the district and delivering them to families, along with basic home goods. Some staff drove from store to store in search of the hardest-to-find items — milk, eggs and toilet paper — using the time and gas they know their clients cannot afford to. Those early issues are starting to calm (toilet paper is back in the aisles, and kids are getting the hang of online learning), but the economic impact of social distancing is taking its place as weeks without income turn into months. Kids need more, and staff still can’t deliver help in person.

For 40 years, Communities in Schools has used a case management approach to confront the numerous roadblocks keeping vulnerable students from graduation: hunger, homelessness, depression and needs as unique as the 1.62 million students the organization serves yearly in roughly 2,500 schools across the country. Until this March, all of these services were provided from a common hub: the school.

School became a constant for their students, a solace and a safe space, said Lauren Geraghty, Communities in Schools of San Antonio’s chief program and innovation officer.

“We know that two-thirds of academic issues have to do with outside-of-school factors,” Geraghty said. “Now kids are outside of school 100 percent of the time.”

In Washington state, a very early hot spot in the pandemic, Communities in Schools State Director Susan Richards is facing challenges similar to those in San Antonio and other struggling communities where CIS has a presence.

“It has amplified every need that was there,” Richards said, “but it has created some new needs and concerns.”

With the outbreak so advanced in her state, she had to pull back staff from the in-person services they so desperately want to deliver, she said. “We cannot do everything for every student because this circumstance is beyond our control.”

Communities in Schools staff are more dependent than ever on the partners that help them get food, mental health resources and other support to families. They are playing their part, in turn, by offering support to others beyond their direct caseload, Richards said. Family members and neighbors have needs too, and by meeting those when they can, she knows they are creating a more stable environment for the students in that system.

The pandemic is making clear what her organization has always believed, Richards explained: that we are connected by the systems we share. Inequality in the health, economic, justice and education systems directly affects the well-being of students. She’s comforted that the organization’s new CEO, Rey Saldaña, shares that understanding as he leads the organization through an unprecedented period.

In times of crisis, those systems do not support us all equally, Saldaña said. As the pressure of the outbreak bears down on communities, he explained, “we start spotlighting what inequity really looks like.”

Being away from the regular routine has changed almost everything about operations, Saldaña explained, but not the needs. They just have to meet them in more volatile scenarios. “We’ve always been primary caregivers,” he said. “Now, we’re EMTs.”

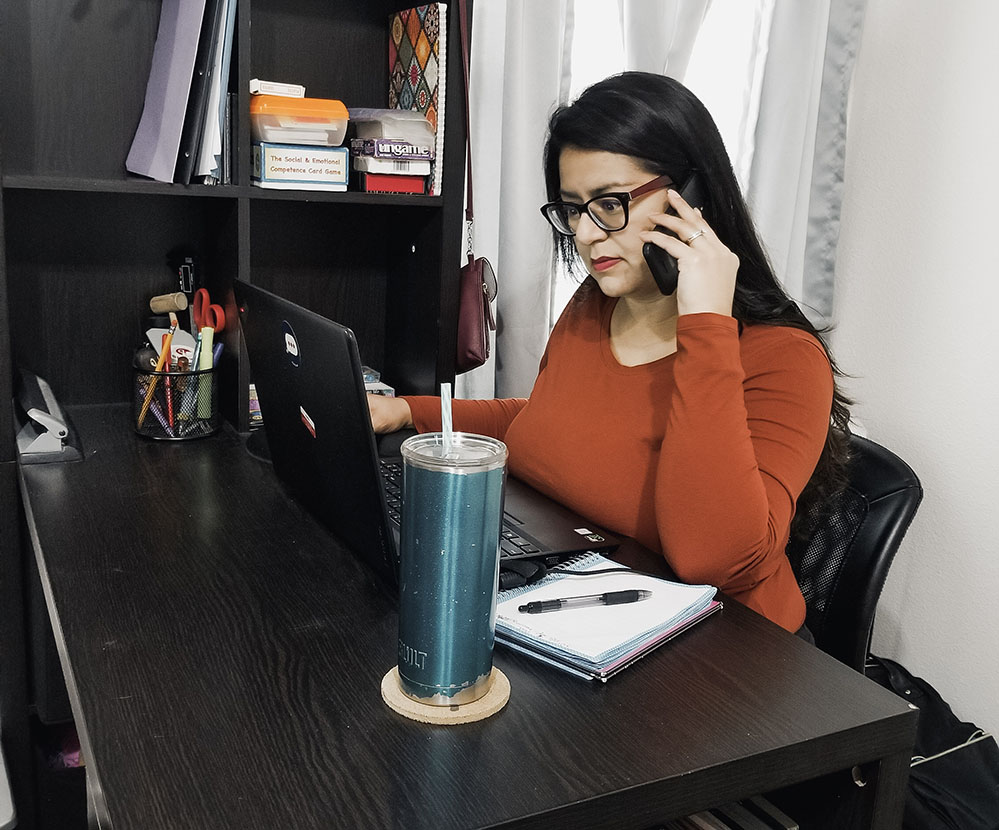

With school buildings locked, Communities in Schools had to find a way to address the growing needs and bring that solace and that safe space to students at home. Phone calls, Zoom groups, pen pal letters, even movie-watching apps have become means of connection for site coordinators and the students they serve — students who, Richards said, are hungry for connection in this uncertain and isolating time.

Connection also gives staff a chance to check on new concerns that may be arising for their students. They knew they couldn’t take for granted that home was a safe place, physically or emotionally.

During the first week of school closures, the Communities in Schools of San Antonio staff spent most of their time trying to get their equipment transferred from schools to home, Google phone lines set up and internet security systems in place. They had never before been allowed to take sensitive student data home with them. New protocols had to be put in place.

Staff also had to learn how to establish reliable records via telephone in case child protective services had to be called at any point. They had to learn national guidelines for telecounseling, since Communities in Schools of San Antonio provides direct clinical counseling services through its own Project Access team. (Most sites broker the services, connecting students to outside providers, who handle the compliance issues.)

Staff are in constant contact with child protective services, homeless shelters and receiving agencies for children who are taken from their homes. When those systems reach capacity, staff explained, that will change their options for how to respond to kids who are in danger.

As they began to make the calls and connect with students, it became clear that while “the [case management] model is solid,” the need was going to escalate quickly, said Geraghty, the San Antonio chief program officer.

Every child and adult in the house became part of the Communities in Schools network, she said, because that’s what it takes to ensure a safe home for students.

For example, in homes where grandparents are caregivers, Geraghty said, Communities in Schools staff started delivering groceries to help protect those most susceptible to the virus.

While the phone calls were going out, she said, their own phones were ringing. San Antonio’s service industries were hit hard and early. Economic pressure from job losses was starting to be felt at home.

That’s likely to get worse, staff agreed, as the recession lengthens.

Melanie Awtry, director of field programs and operations with Communities in Schools of San Antonio, is also making sure staff are prepared for some of the stories they will hear as the crisis deepens. They need to be ready to process stories of trauma, with a realistic understanding of what they can and cannot do to help. In addition to varying shelter-in-place orders, staff have their own families to care for and their own health to consider if they want to be able to help kids for the duration of the emergency, she said.

The national organization, which has an annual budget of $200 million, will also need to tend to its financial health to keep services flowing.

Funders have been remarkably flexible, Geraghty said, allowing Communities in Schools to pivot funding to meet new and expanding needs. Many have deferred reporting requirements so that the whole staff can focus on the needs at hand, not paperwork.

The pandemic and resulting economic collapse have also led many to increase their giving or release crisis funds.

“We’re almost in this honeymoon period where a lot of money is coming in,” Richards said, “because people have the feeling that we’re all in the same boat.”

It may feel like that today, she said, but what about tomorrow? The San Antonio chapter is currently trying to raise $25,000 to ensure its financial health in the near future, after canceling its yearly fundraiser, according to data tracking nonprofit SA2020, which has been keeping a dashboard of nonprofit financial needs during the pandemic.

As testing and fatality rates grow, it’s become clearer that underlying health conditions, lack of health care, crowded living arrangements and on-the-job exposure for working-class and low-income neighborhoods and communities of color are making them more vulnerable to coronavirus infection and more likely to suffer complications.

Experts are even more sure about which communities will be most impacted by a recession. With nearly 40 million Americans having filed for unemployment since mid-March, many in low-wage positions, the forecast is bleak, and Communities in Schools is preparing for the worst as best they can, Saldaña said.

While he has had to conduct his entire first few months of work from his home office in San Antonio, Saldaña has reached out to city-specific staff to lead webinars on how their organizations weathered the trauma, homelessness and economic strain that followed 9/11, Hurricane Katrina and the Great Recession.

They are learning from each crisis, he said, but they all agree, “This is completely different from everything we’ve seen before.”

Correction: Lauren Geraghty is the chief program and innovation officer for Communities in Schools of San Antonio. Her name was misspelled in an earlier version of this story.

Lead Image: Siblings Brandon and Addyson, students in the San Antonio Independent School District, show off an H-E-B grocery store gift card that Communities in Schools provided to families in need. Many couldn’t get to local food pantries because they lacked transportation or could not leave other family members to wait in line for hours. (Communities in Schools)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter