Teens Don’t Trust Ads for Financial Aid. Why California Is Polishing Its Pitch

The state is striving to use authentic feel in new social media campaign.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Even when California high school seniors set a record last year in applying for college financial aid, more than a quarter didn’t bother, leaving gobs of money on the table.

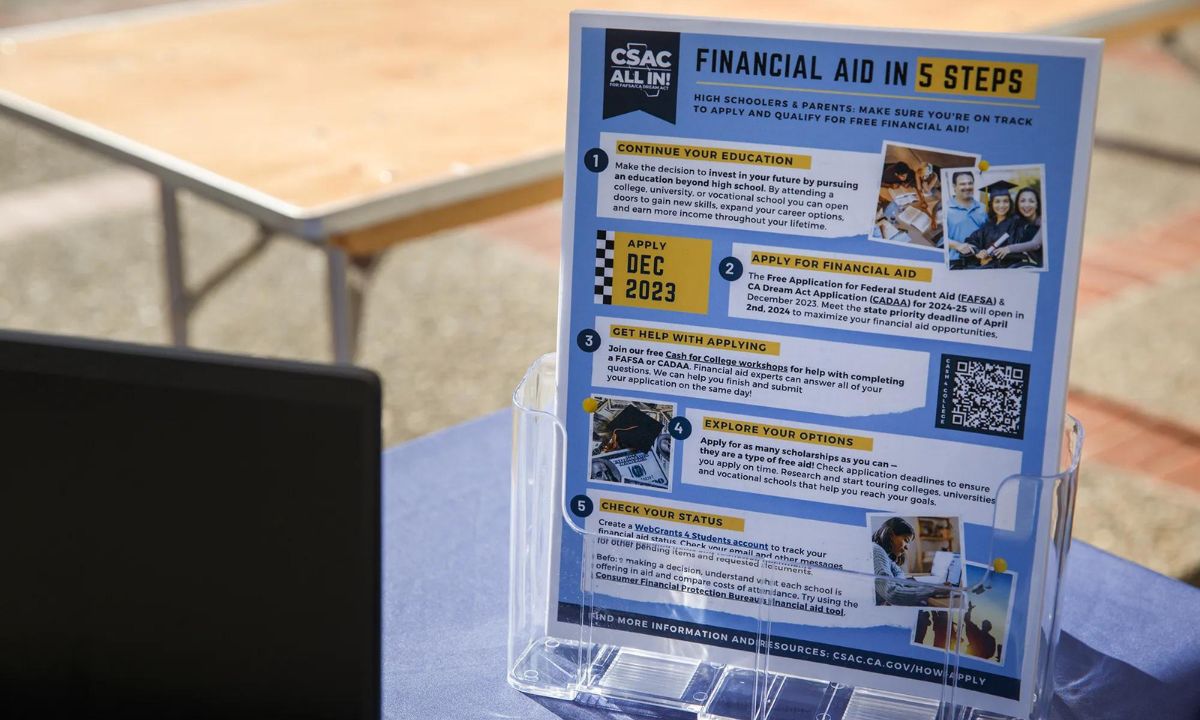

Now, the state agency overseeing student grants and scholarships is about to embark on a new campaign to persuade more students and their parents to apply for financial aid. The strategy is buttressed by novel market research that produced counterintuitive conclusions about what compels people to seek cash for college.

It can’t come at a better time as financial aid applications in California and nationally are down compared to last year, largely due to major setbacks with the federal government’s revamped application for aid.

Core to the research insights is that low-income parents and students know that a college degree often leads to higher wages, but they have significant anxiety about paying for that education.

“Nationally, we are grappling with this question about, ‘How do we communicate to students about the value of an education after high school and the return on investment?” said Jake Brymner, deputy director of policy and public affairs at the California Student Aid Commission.

Avoiding language that sounds too good to be true, such as “100%” of tuition covered, even if that’s technically accurate, was one lesson learned from a round of focus groups led by a public opinion research firm that the student aid commission hired with philanthropic funds. Imagery such as coins or bags of money implied scams, not the promise of affordability, the panel of parents and students told the market researchers.

And video testimonials from students who were frank about their ambivalence toward pursuing college, but mustered the will anyway to apply for financial aid, resonated deeply with participants of the focus groups, which took place between December and April.

“It was surprising to see that ‘free money,’ a phrase like that, leads to distrust at times,” said Michael Lemus, a marketing manager at the student aid commission who helps with developing videos the agency produces to explain the intricacies of applying for financial aid.

Added Sara Beth Brooks, who’s also on the team: “The basic values behind our social media channels is that we believe we can cut through government jargon and take information directly to constituents.”

Language on financial aid is persuasive

A survey conducted between May and June of nearly 1,200 high school students and parents showed an 11 percentage point jump among those who said they were likely to apply for financial aid, from 61% to 72%. The participants were asked if they would apply and then asked a second time after viewing the refined marketing material, which included a mix of video testimonials and written material across 20 minutes.

The idea to examine the best ways to reach students was born out of a commissioners’ retreat last year. The findings from the focus groups and the survey were presented to commission members Thursday. CalMatters was given an advance copy of the results.

“Everyone talks about ‘you got to strengthen your communications, meet students where they’re at,’” said Marlene Garcia, the outgoing director of the student aid commission, at the meeting. “It isn’t as easy as it sounds. It’s hard, and this team is figuring it out.

The likelihood of completing the state or federal financial aid applications jumped from 54% to 68% among the groups the California Student Aid Commission considered a priority — students with grades below a B or C average, those who were in low- and middle-income households and students who hadn’t taken the core high school courses required for admission to the state’s public universities.

State tuition waivers and federal cash grants that don’t have to be repaid can fetch students as much as $21,000 or more, per year. Without completing financial aid applications, that vital postsecondary assistance is unattainable.

“If we communicate effectively and meet people’s emotional needs, we can increase the likelihood that people will pursue” applying for financial aid, said Robert Pérez, one of the researchers behind the marketing analysis, at the meeting. He’s the founder of public opinion firm Wonder: Strategies for Good.

Specificity mattered to audiences, as well. It’s not enough to say “financial aid.” Parents and students were more drawn to messaging that stressed state and federal grants aren’t loans and don’t have to be repaid.

“I feel more calm knowing these are not loans, but aid,” wrote one mother during the focus groups.

Putting the findings on student grants to work

This summer, the outreach and marketing team will use philanthropic dollars to hire content creators on social media with large followings to publish videos about their own experiences seeking financial aid and completing community college. The team will time that with the Sept. 3 deadline for first-time community college students to apply for the Cal Grant, the main financial aid benefit in California.

The video team at the student aid commission will also feature more personal anecdotes about their paths into college. In another effort to appeal to students who haven’t applied for aid, the commission also will send recent high school graduates postcards with language and imagery informed by the focus groups.

The aid commission was already connecting on social media with students, parents, high school counselors and other professionals involved in the financial aid application process. One video in January generated more than 6 million views on Instagram. It featured Brooks describing a step-by-step process to answer a confusing question on the new federal financial aid application.

The number of followers across the commission’s social media channels has grown prodigiously this past academic year. Last year it had 5,200 followers on Instagram and 800 on TikTok. This May, those grew to 58,000 followers on Instagram and 35,000 on TikTok.

“We could make graphics that explain these things, and I don’t think that they would do as well,” Brooks said. “It’s the human element of somebody saying, ‘I hear that you’re in this situation, I’m going to do everything I can to help you.’”

The videos aren’t slick by design — they often show a member of the outreach team in the car or in their office speaking candidly about how confusing applying for financial aid can be, especially this year when the newly revised federal application encountered a bevy of problems that blocked many students from submitting their applications.

Videos with low production value, high emotional impact

That humility resonates well with audiences, the focus group participants.

A video shown to them earlier this year featured a mother who spoke only in Spanish and her son, who spoke in English, sitting in front of a wall decorated with a crucifix and family photos. The video purposely avoided the slick digital treatment common in advertisements and instead appeared more like a low-budget documentary.

At one point the student, Kenny Funes, said he never felt poor because his parents provided for him, but he was surprised to learn that he qualified for a lot of financial aid because his family’s income was sufficiently low.

Another video was in Spanish and featured an undocumented student who applied for state aid. This and other videos were unscripted and edited down from about 75 minutes to under 3 minutes.

In a final video, a college student spoke about dropping out of high school and then feeling inspired to resume his education. As he’s speaking, the focus group participants respond in real time to how the video content makes them feel. Initially, the mood among the participants drops as the student describes the dead-end jobs he was working. Seconds later, the student recollects a phone call with his mom after she received distressing news from her doctor. That prompted him to return to college. The audience mood starts to climb, responding well to the narrative arc of temporary setback and eventual triumph.

The researchers said that had the videos just emphasized success, they wouldn’t connect as much with the audiences. “When we feel like we’re not alone, we feel like we can do it,” Pérez said. The sincerity prompts the audience to trust the student, which in turn encourages more people to complete the application, he added.

“I understand that frustration…not wanting to fill it out,” the student in the final video, Jesse Williams, said of completing the financial aid application. “Because it is a process.”

Pérez and some of the commissioners also agreed that reaching parents directly will compel more students to apply for aid.

“I feel like the one thing that keeps a lot of students from trying, especially first generation students, is that their parents don’t know where to even start,” said Keiry Saravia, a student commissioner.

“Parents are incredibly important messengers and really underutilized,” Pérez said.

The story was originally published on CalMatters.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter