In 1990, the Kiryas Joel school district opened its doors — and controversy has followed it ever since.

Not only did its creation spark a lengthy court battle over church-state separation that reached the U.S. Supreme Court, investigators have cited the district three times for conflicts of interest and other questionable financial practices.

Founded in order to uphold centuries-old, ultra-Orthodox traditions, the tiny district in New York’s Hudson Valley caters exclusively to families in the Satmar sect of Hasidic Jews who have children with disabilities. It remains largely closed to public scrutiny.

Most recently, school officials refused to address how the system of less than 500 students is spending nearly $94 million in federal pandemic aid designed to curb learning loss and other effects of one of the worst disruptions to education in American history.

To put that amount in perspective, in the last round of funding alone, the Kiryas Joel Village Union Free School District received over $95,000 per student — nearly 40 times the national average and more than double what New York schools spend on special education students.

Its use of those funds could raise eyebrows. Documents The 74 obtained from the state reveal the district is investing over $12 million in upgrades to facilities owned by organizations affiliated with the religious group’s leadership.

The pandemic’s exceptional windfall calls out for a high level of transparency and accountability from a school system with little to no separation from a ruling religious community that has openly — and successfully — resisted government oversight.

But the district has avoided repeated requests from The 74 to address how it used the money. Since October, Kiryas Joel officials have ignored a public records request filed under the state Freedom of Information Law, and Superintendent Joel Petlin declined to answer questions by email, phone and on social media.

The district also advised others not to talk to reporters about its COVID spending. A contractor who made relief-funded improvements to a district-leased building provided some information to The 74, only to text a reporter the next day asking not to use any of it because “the school simply asked that we not share anything.”

School systems in New York and nationwide are required to publicly post their stimulus spending plans online, but Kiryas Joel never has. It doesn’t even have a website.

“[The district] is always an outlier in dollars received and in some of the way they do things,” said Brian Cechnicki, executive director of the Association of School Business Officials of New York and the former director of education finance at the New York State Education Department. “It’s a tough nut to crack.”

When The New York Times raised issues about the district’s relief spending in February, Petlin called it a “false narrative.”

“The public would have been better served by a story that helps it understand this unique and truly special school district and community and celebrates the remarkable work being done here,” he said in a statement.

Petlin argued that the district’s use of federal funds was approved by the state education department, but oversight could be less than rigorous. Cechnicki, who left the department in 2020, said “There is a high volume of these types of reports that have to be approved, and the department perennially doesn’t have the capacity to do fine-grained reviews of all 700ish districts.”

Nonetheless, the state selected Kiryas Joel as one of about 16% of districts to receive its highest level of monitoring for relief spending, requiring a full-day, on-site examination of documents and staff interviews. The state has between January 2023 and June 2024 to complete the on-site visits; it’s unclear when Kiryas Joel’s will happen.

The results of that investigation — like nearly all information on local relief fund spending — won’t be easy for the public to access. New York requires anyone seeking such data to submit open records requests. That makes it tough to track how districts used the money to address even broad areas such as hiring staff or addressing learning loss.

New York’s approach contrasts with states like Indiana and New Hampshire, which provide online portals where the public can keep up with how much districts have spent and in what categories. New York’s lack of transparency has kept parents largely in the dark about whether the historic expenditure is having an impact, advocates say.

“There’s no sharing of best practices. There’s nothing around evaluation. It’s a missed opportunity,” said Jeff Smink, deputy director at The Education Trust–New York. “There needs to be more urgency around this.”

Private school bonus

One reason for the state’s heightened scrutiny of Kiryas Joel might be the sheer amount of federal relief money it received — so much that Deputy Superintendent Josh Kamensky told the Times that it was “really hard to spend.”

That amount —for a district with less than 500 students, including preschoolers — was 12 times what the Ellenville Central School District to its north received for a district of over 12,000 students and more than five times what the 2,700-student nearby Monticello district received.

The mismatch in Kiryas Joel’s favor is rooted in the arcane machinery of federal spending, which is weighted to support those living in poverty.

“We have no discretion to keep this money for our public school students and every federal dollar spent is approved by the NY State Education Department.”

Joel Petlin, superintendent, Kiryas Joel school district

In the first wave of pandemic funding, the district, with an 86% poverty rate, received almost $7.6 million. That law followed the traditional Title I formula that requires the district to provide “equitable services” for low-income children, even though the vast majority of those students in Kiryas Joel attend private schools. The bulk of the money, $5.4 million, went to over 5,500 students in 21 yeshivas, private Hasidic schools that strongly prioritize religious study over academics.

In his statement on the Times article, Petlin noted the district’s responsibility to provide those services. “We have no discretion to keep this money for our public school students and every federal dollar spent is approved by the NY State Education Department,” he wrote.

But the second and third pandemic relief packages had no such requirement for private school students. Nonetheless, the funding formula continued to factor in the high level of poverty in the greater community, including those students who don’t attend public schools. That left more than $86 million for a district with few students.

“In a weird way, the district benefits from having the kids in the private schools and no longer has to share it.”

Marguerite Roza, director, Edunomics Lab, Georgetown University.

One of the nation’s foremost experts in school finance suggested federal officials should have adjusted the formula for the latter waves of funding to avoid an outcome some might view as perverse.

“In a weird way, the district benefits from having the kids in the private schools and no longer has to share it,” said Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University.

Conflicts of interest

Another reason for investigators’ increased focus on Kiryas Joel might be that it has run afoul of them before:

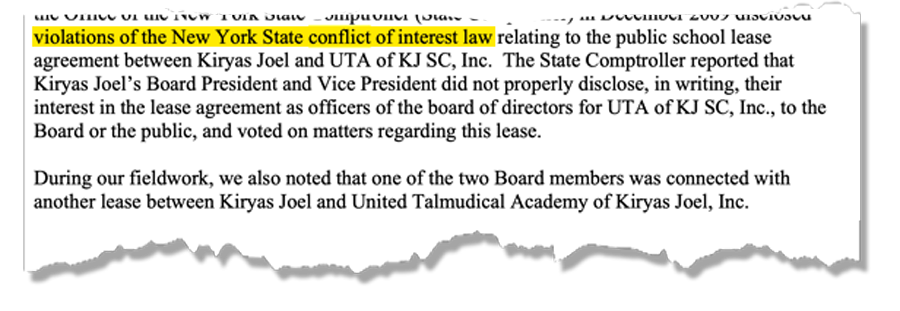

- In 2009, a state comptroller’s audit showed that the district violated conflict of interest law when two board members failed to disclose that they are also on the board of United Talmudical Academy of Kiryas Joel, which runs a network of yeshivas. The Kiryas Joel board members voted in favor of a lucrative, long-term lease to rent a building owned by UTA of KJ.

- In 2011, the national education department’s Office of the Inspector General found that the district put $276,443 in Title I funds toward the cost of the lease for the school and a second lease for another UTA of KJ building used for afterschool programs for yeshiva students. “Because decisions surrounding both lease agreements were influenced by the board members with evident conflicts of interest, there is no assurance that the decisions made were in the best interest of the students of Kiryas Joel,” the audit found. The district had to repay the funds.

- The same report showed the district could not account for over $191,000 in “significant overtime” pay charged to Title I. Timesheets for those receiving the extra money didn’t identify the program they were working on.

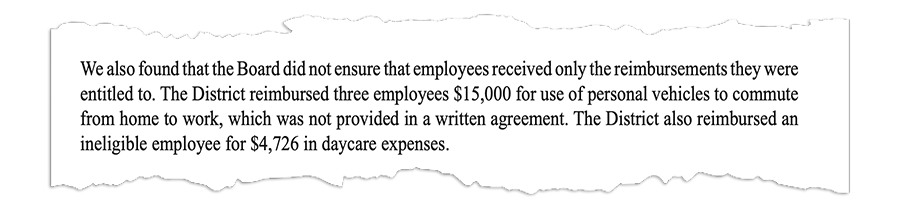

- Finally, in 2017, the state comptroller issued a report that found the district reimbursed three employees a total $15,000 for commuting to work even though it wasn’t part of their employment agreement. Petlin responded that it was an oral agreement, but said it would be documented in the future. Another employee was reimbursed over $4,700 for child care expenses despite being ineligible for that benefit.

The Times — in a series of articles on education at the yeshivas — raised new questions about the propriety of payments made to UTA of KJ with relief funds, including $1.3 million in lease payments and another $288,000 to rent the organization’s swimming pool.

Two sons of school district board member Harry Polatsek — also on the board of UTA of KJ — have connections to the district, the Times found. One runs a bus company that received a $656,000 contract paid for with relief funds. And the other is on staff as a teacher’s aide, emergency medical technician and parent liaison. Documents obtained from the state education department show the district is spending $1.1 million in relief funds on parent liaisons, but don’t list employees’ names.

The relationship between the district and its landlord demonstrates “a habit of interpreting the law on their own terms and for their own benefit,” said Beatrice Weber, executive director of Young Advocates for Fair Education, a nonprofit seeking to improve secular education in New York’s Hasidic schools.

Many of the district’s big-ticket expenditures are upgrades to buildings it leases from UTA of KJ and its affiliates. In his statement, Petlin said any improvements “benefit our students, and not our landlord.”

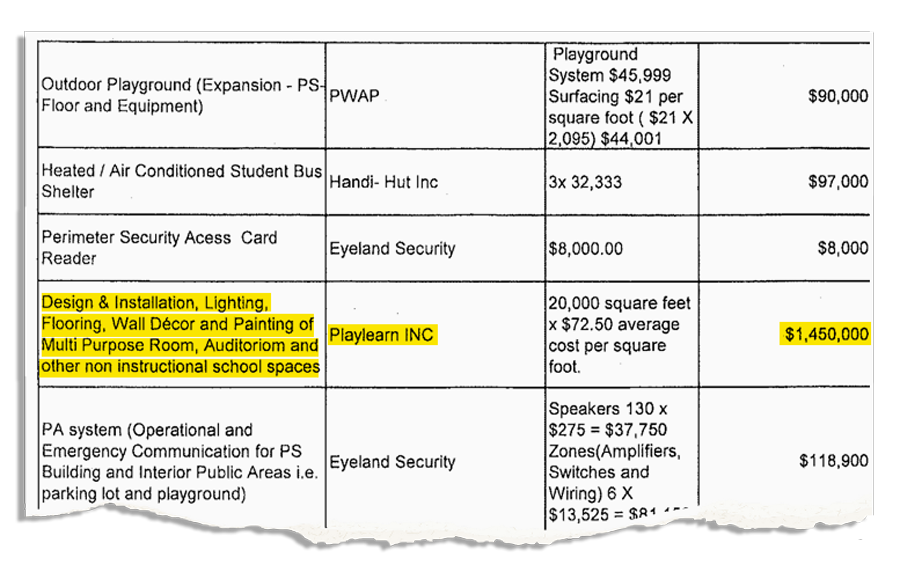

But The 74 has found the district is spending over $12 million in improvements to the building it rents — re-doing the flooring, replacing the HVAC systems, re-paving a parking lot, adding a classroom audio system, installing an outdoor playground and building a temperature-controlled “bus shelter.”

Nearly $3 million went to Playlearn USA, which specializes in classroom furnishings for students with disabilities. The company is installing “sensory” features — such as a wall with flowing water and bubbles lit up by LED lights — at the school.

“The sound of the water with the lights and the bubbles in the wall are instantly relaxing,” said Shevy Schlesinger, director of business at Playlearn. Many of the purchases include furniture and equipment that could be removed like swings or climbing walls, she noted. But she acknowledged also making improvements to permanent structures like the floors and ceilings.

Kiryas Joel is not alone in renting, instead of owning, a school building. Mary Filardo, executive director of the 21st Century Schools Fund, a nonprofit focused on modernizing schools, cited a 2021 example in which the Newark Public Schools in New Jersey signed a 20-year, $160 million lease with private developers to renovate a former hospital into a high school.

“It’s a classic real estate transaction. There’s nothing unusual about leasing a building and making improvements that you pay for,” she said. But since it’s public money, she added, “The duty to make it transparent is really high. Even if there’s a little bit of abuse, it poisons the well.”

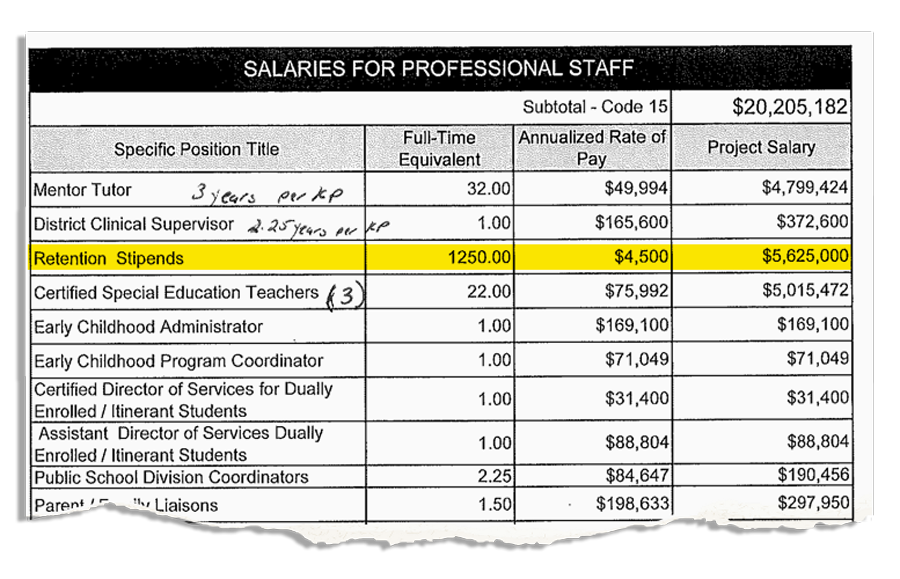

The district is also spending a total of over $34 million in relief funds on salaries for administrators, specialists and support staff, according to documents filed with the state. While districts across the country have spent relief money this way, experts like Roza warn that using temporary funds to pay employees raises questions about a district’s ability to afford those costs when the money runs out.

Another $5.6 million was allocated for employee “retention stipends” of $4,500 a year for three years. The district has “around 500 staff,” according to J.P. O’Hare, spokesman for the state education department. He cited federal guidance allowing retention bonuses as a way to reopen schools and provide stability for students and staff.

But the state put the brakes on at least one planned expenditure. It rejected the district’s initial plan to use relief funds to build a wellness center, according to the Times Herald-Record, which covers New York City’s northwest suburbs.

The department declined to answer questions about any of the district’s purchases or whether it had concerns about potential conflicts of interest, but said Kiryas Joel was selected for more aggressive monitoring based on risk.

Kristina Naplatarski, a spokeswoman for the state comptroller’s office, which conducted the 2017 audit and issued a report in March noting the urgency of spending COVID relief money to address learning loss, declined to comment on the issue because they had not “recently audited the school district.”

The district did spend $3,000 to hire a well-known Washington, D.C., law firm that specializes in federal compliance and audit preparation as part of its COVID relief spending. Bonnie Graham, a partner at Brustein and Manasevit, would not answer questions about the specific work the firm did for Kiryas Joel.

‘Fiscal stress’

The 74’s reporting on Kiryas Joel is part of an ongoing effort to track how districts around the nation are spending $3.4 billion in COVID funds. On Nov. 1, a member of the district’s staff confirmed that Petlin, the superintendent, received The 74’s original open records request. But he and Kamensky, the deputy superintendent who prepared forms for the state related to the funds, never followed up, despite repeated attempts to reach them.

This isn’t the first time Petlin failed to comply with the Freedom of Information Law. In 2008, the Empire Center for New York State Policy, a conservative think tank, sued the district after it didn’t turn over employee contracts as part of a public records request.

This also isn’t the first time Kiryas Joel received a disproportionately large influx of federal cash. In 2010, the district got $1.6 million in the federal Race to the Top competition — more than the majority of New York districts. But when the funds ran out three years later, the state comptroller found the district to be in “significant fiscal stress.” In a response, Petlin noted that the district’s financial condition had improved between 2013 and 2016 because it was maintaining adequate reserves.

Early in the pandemic, however, the state again listed the district as “susceptible to fiscal stress,” largely for its reliance on cash to pay monthly expenses and short-term debt.

The focus on the district’s relief spending comes amid renewed attention to the poor academic performance of students who attend private schools in the village and other ultra-Orthodox communities in New York state. A Times investigation found that students who attend yeshivas — many of whom also attend district public schools for remedial services — are failing to gain the foundations of a secular education, with little ability to spell or do basic math.

Weber, with Young Advocates for Fair Education, said she knows parents in Kiryas Joel who worry that their children who attend yeshivas are not learning the skills necessary to be employed and function as adults.

“I have parents calling me from there crying and begging, ‘What are you going to do about this?’” she said.

‘This educational experiment’

The creation of this most unusual school district just an hour north of New York City grew out of tensions with its neighbors.

Before Kiryas Joel created its own school system, students who needed special education attended public schools in the neighboring Monroe-Woodbury Central School District.

“There is more than a fine line between the voluntary association that leads to a political community comprised of people who share a common religious faith, and the forced separation that occurs when the government draws explicit political boundaries on the basis of peoples’ faith. In creating the district in question, New York crossed that line.”

Anthony Kennedy, former Supreme Court justice

But conflicts arose when schools didn’t accommodate the Hasidic families’ religious practices — like wanting women bus drivers for girls and men for the boys. A new school system, leaders argued, would support its traditions and shelter students from ridicule.

New York Gov. Mario Cuomo signed legislation creating the district in 1989. Lou Grumet, then-executive director of the state’s school board’s association, sued on the grounds that it violated the constitutional separation of church and state.

The Supreme Court agreed. In a 6-3 decision, former Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote: “There is more than a fine line between the voluntary association that leads to a political community comprised of people who share a common religious faith, and the forced separation that occurs when the government draws explicit political boundaries on the basis of peoples’ faith. In creating the district in question, New York crossed that line.”

But the political fight waged on. Because their residents vote as a bloc at the direction of their most senior religious leaders, Kiryas Joel and other ultra-Orthodox communities have traditionally wielded significant influence over New York politicians. The Hasidic sects can both block legislation they deem unfavorable and cement support for causes they want championed.

After the Supreme Court defeat and subsequent legal battles, New York lawmakers went through several rounds of legislation before they finally adopted a law that allowed Kiryas Joel’s one-of-a-kind school district to survive subsequent legal challenges.

Today, the relationship between Kiryas Joel and Monroe-Woodbury is more “collegial,” according to Superintendent Elsie Rodriguez. In fact, the two districts now have a reverse arrangement in which Monroe-Woodbury pays Kiryas Joel to serve 23 of its special education students.

Petlin, meanwhile, remains Kiryas Joel’s most outspoken advocate. In an op-ed on the school district’s 30th anniversary in 2020, he wrote: “We have proven that this educational experiment works, contrary to the naysayers of yesterday and today.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter