Leaders in California and South Carolina Find Learning Loss — Especially in the Early Grades — But Experts Say Data is Still ‘Imperfect’

When leading assessment providers released data in November on pandemic-related learning loss, the news wasn’t as dreadful as some had predicted.

But new attempts to dig deeper into the results from two states now show that many students, particularly those in the elementary grades, have made far less progress than they would have in a normal school year.

In California, the negative effects of school closures on academic progress appear greater for English learners and students from low-income families — the very groups that experts have predicted would bear the brunt of remote learning. And in South Carolina, Black students made fewer gains in reading and math in fall 2020 than they did in 2019, but learning loss was even greater among white and Hispanic students.

The new research points to “the difficult work and opportunity that lies ahead in the public K-12 system,” said Margaret Raymond, the director of the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University. “We haven’t started the blame game yet, but I am sure it’s coming soon.”

In October, the Stanford center released estimates of learning loss across 19 states. The grim calculations ranged from students falling as much as a year behind in reading and 232 days in math.

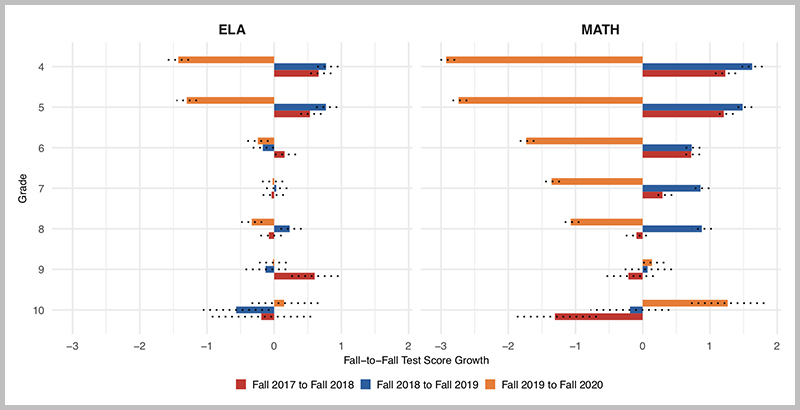

But a month later, the reality didn’t look as bad as some had feared. Results from the Northwest Evaluation Association, or NWEA, as well as two other assessment groups, Renaissance and Curriculum Associates, generally found little to no decline in reading, but revealed that students had fallen behind in math compared to where they would have been without school closures.

The latest findings from California and South Carolina suggest that November’s results about the damage of distance learning shrouded variations among grade levels, demographic groups and geographic regions. The results line up with Raymond’s earlier predictions about learning loss and provide more specific data for those planning recovery efforts at the state and local level.

California

To learn more, a network of California districts known as CORE analyzed fall NWEA and Renaissance results for students in 18 districts, all of which serve high numbers of English learners and students from low-income families.

Policy Analysis for California Education, a think tank, wrote up the results, noting that it was one of the first attempts to break down differences in learning during the pandemic according to family income and language status.

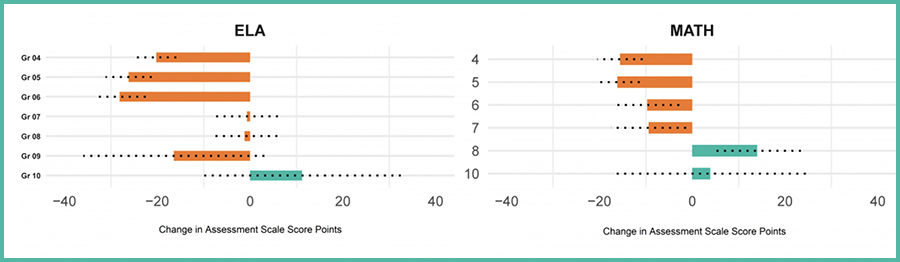

Fifth graders in the California sample of 50,000 students, for example, lost roughly two points on NWEA’s Measures of Academic Progress, or MAP, assessment in reading and math, while in a typical year, they would have gained 10 points. On the Renaissance STAR assessment, sixth graders lost almost 30 points in reading compared to normal progress, a gain of about five points.

The scores of disadvantaged fourth-graders grew at a slower rate in English language arts, while peers from wealthier families gained more than they would have in a typical year. Large gaps in reading between English learners and other students appeared in fourth, seventh and eighth grade MAP tests.

It’s important to examine the data by race, family income level and language status “because we see different patterns,” said Libby Pier, a research manager at Education Analytics Inc., a Madison, Wisconsin-based nonprofit that worked with CORE.

Policymakers are urging districts to measure the pandemic’s impact on student learning, but with officials seeking federal government waivers on state-mandated assessments for a second year, tests like MAP serve as stand-ins to track learning loss. There are significant limitations, however, at a time when a lot of students didn’t even take the tests and the samples of those who did weren’t large.

Experts from NWEA and Renaissance agreed that it’s important to look at the impact of school closures on student learning at the state and local level. And Scott Marion, executive director of the New Hampshire-based Center for Assessment said researchers are attempting to “put some data to the questions people have.”

But he cautioned that as long as remote learning interferes with typical assessment practices, researchers are working with “very imperfect and likely confounded data.”

South Carolina

The South Carolina sample is also a snapshot — about 95,000 students across 34 of the state’s 85 districts. Compared to NWEA, South Carolina’s sample included higher percentages of Black and Hispanic students.

The patterns that emerged varied from those Pier observed in California. Pier found that while Black students in fourth and fifth grade experienced some learning loss in reading on the MAP assessment, the decline was greater for students in other racial groups. In fact, in sixth through ninth grade, Black students gained more than they would have in a typical year.

Gaps between English learners and other students weren’t as large in South Carolina as they were in California.

Ryan Brown, spokesman for the South Carolina Department of Education, said the finding that Black students lost less ground than that of other groups was a surprise since many attend school in high-poverty districts. But he added that in the mid-year data Pier is currently analyzing, it’s clear that for “those students in a classroom, with a teacher, their gains are higher.”

The state is currently asking districts to submit plans for how they plan to address the gaps.

In California, Rick Miller, executive director of CORE, said districts are also discussing strategies such as extending the school year.

“It’s still hard, though, not knowing where we’ll be COVID-wise,” he said. “A bulk of the conversation is also rooted in how to try and ensure quality as opposed to just extension of time.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter