Hundreds of U.S. High Schools Wrongfully Refused Entry to Older, Immigrant Student

In 35 states, students have a right to attend high school until at least age 20; a 74 investigation revealed a 19-year-old was repeatedly turned away.

By Jo Napolitano | June 17, 2024

In 35 states, students have a right to attend high school until at least age 20; a 74 investigation revealed a 19-year-old was repeatedly turned away.

“He is not going to achieve the end result: He is never going to finish high school in the time he has.”

– registrar

“Does he speak good English?”

– school counselor

“We wouldn’t be able to have a 19-year-old with 14-year-olds.”

– family engagement counselor

“At the end of the day, what is the person doing if they can’t get a diploma? ”

– principal

“I don’t think we could deny, but him being much older than the other kids … he wouldn’t get to participate in extracurriculars.”

– principal

“Our adult ed would be the place for him.”

– counselor

Updated

Sometimes, it takes just a few seconds for a high school staffer to end a newcomer student’s educational career.

Other times, it can take slightly longer for a gentle push to morph into a shove as secretaries, registrars, counselors and principals say, with increasing irritation, that older immigrant students are destined to fail.

Bottom line, they insist, these new arrivals are not worth enrolling.

“He’s going to come to us and he’s going to be a dropout,” Paul Measso, director of school counseling at New Jersey’s Kearny High School, said when asked to admit a 19-year-old Venezuelan transplant as part of an undercover investigation by The 74.

It took Measso a mere three minutes to deny the teen, even though all students have a legal right to attend high school in New Jersey through age 20.

Whether a refusal comes in an instant or after a lengthy back-and-forth, the result is the same: a door critical to success in America is shuttered.

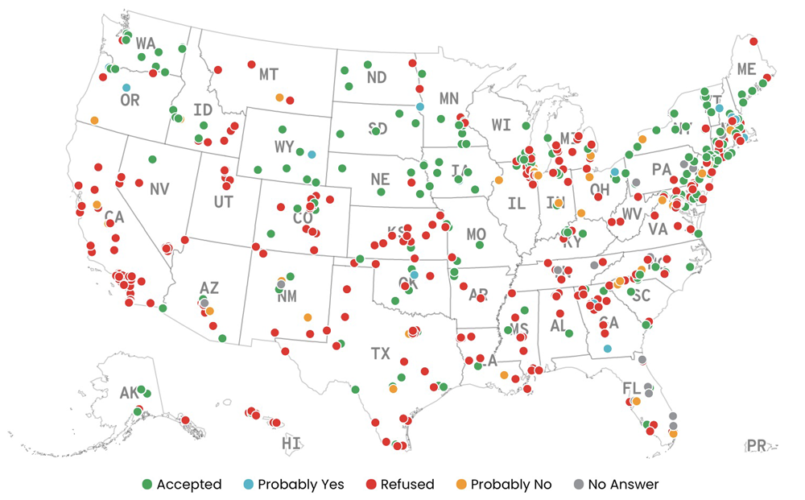

The 74’s 16-month-long investigation found such rejections rampant. The news outlet tested the enrollment practices of more than 600 high schools in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., attempting to register a 19-year-old who spoke little English and whose education had been interrupted.

INTERACTIVE

School Admission Responses

- Accepted

- Probably Yes

- Refused

- Probably No

- No Answer

More than 300 schools refused to register him — including 204 denials in the 35 states and the District of Columbia where high school attendance goes up to at least age 20. State officials in almost all these locations separately confirmed to The 74 that a 19-year-old could not be turned away because of his age. A few did not respond.

“It saddens me to hear that in 2024, we are still denying kids a right to an education and a shot at a diploma,” said student immigration advocate and policy expert Timothy Boals. “It’s pathetic that this continues to go on.”

The 74’s investigation also revealed:

- High school enrollment for these students is arbitrary and unpredictable: Schools in the same state, the same county and the same district gave contradictory answers. Different staffers within the very same building sometimes disagreed, proving it didn’t matter where our test student landed, but on who picked up the phone that day.

- There was no uniformity in who answered this high-stakes question and their responses were rife with bad information. Hundreds of employees, including temporary office staff, replied without hesitation, seemingly unaware or misinformed about their state’s regulations.

- Many staffers who agreed to enroll our newcomer did so begrudgingly. A third of the acceptances came at the tail-end of long, contentious calls — and only after school employees were asked whether their “firm recommendation” that the student go elsewhere meant he was refused. Only then did many acknowledge the law in their state and admit him.

- Several staffers said he could enroll, but that his participation would be severely limited: Some would allow him to take only ESL classes while others barred him from extracurricular activities. Such disparate treatment is illegal under federal civil rights laws.

- Many required birth certificates upfront even though federal guidelines say schools “may not prevent or discourage” students from attending without them. Others demanded transcripts before even considering enrollment. There was no consistency in how these rules were applied within states or districts.

- Some staffers tied the enrollment request to citizenship. They asked repeatedly about visas, insinuating that the new arrival was pursuing his education only to improve his immigration status. Federal civil rights laws require that school districts enroll all students regardless of their or their parents’ or guardians’ “actual or perceived citizenship or immigration status.”

- Of the hundreds of staffers who refused or discouraged our test student, many said he would age out before completing high school while others noted his peers had already graduated. Advocates and several state education officials said newcomers should not be singled out based on predictions about their future. Many students across the board fail to graduate but schools don’t prevent them from attending.

Overall, The 74’s investigation revealed pervasive hostility and suspicion toward these students in a particularly xenophobic era, as evidenced by the current presidential race. Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee, said in December that immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country” and more recently called undocumented people “animals.”

At the same time, conservative forces are strategizing to overturn Plyler v. Doe, the landmark 1982 Supreme Court ruling that a child cannot be denied a public education based on immigration status.

“I’m not surprised that [older immigrant students] are routinely rejected,” Adam Strom, founding director of Re-Imagining Migration, told The 74. “I’m surprised by how high the percentage is. That’s shocking.”

Hard ‘noes’ and harder ‘yeses’

Roughly 1.1 million people ages 18 to 20 entered the United States between 2012 and 2021, according to the Migration Policy Institute.

High school, advocates told The 74, is a place where they can build strong relationships with peers and teachers and learn to navigate life in a new country.

Enrollment means they’ll hear English all day long, which helps newcomers learn the language far faster than if they attended an alternative program for just a few hours each week. And they can progress in other subjects as well while forging inroads to college or better positioning themselves for employment.

Our test student was a stand-in for these older, new arrivals, whose rejection by the nation’s public schools goes unrecorded. To capture how schools react to such registration requests, The 74 senior reporter Jo Napolitano presented herself as a private citizen trying to enroll her 19-year-old nephew, “Hector Guerrero.” Using her own name, she told school officials Hector had arrived in the United States just weeks earlier and was eager to continue his education.

“To be explicit, it’s going to be a waste of time,” said Jim Karedes, principal of Delavan-Darien High School in Wisconsin, where students can legally stay in public school until age 20. “We could babysit him and that’s about what it would be. It would not behoove him to go down this pathway. He is 100% going to be a dropout.”

Pressed to say if this meant the school would not allow him in, Karedes admitted Hector.

After our initial contact seeking to enroll our test student, The 74 reached out multiple times to every staffer and school named in the story. Napolitano explained the circumstances surrounding their original conversation and gave them an opportunity to respond. Most did not; read the responses of those who did comment here.

Of the 630 schools Napolitano contacted, 209 agreed to enroll him, 330 refused him, 17 said they would probably accept him and 48 indicated they likely would not. Twenty-six never responded despite numerous follow-up calls.

DATA ANALYSIS

Refusals Far Outnumbered Acceptances for 19-year-old Test Student

Napolitano advocated for the teen in a way that would be difficult — if not impossible — for immigrant students or their families. Many do not speak English and are unaware of their legal rights, leaving them ill-equipped to contest rejections or resist steering to alternative programs.

In order to count as a refusal, staffers had to outright deny Hector’s enrollment, rather than merely state — as many did, forcefully — that he belonged in a GED program, adult education or community college.

After rejecting him, one high school staffer in Oklahoma, where the maximum enrollment age is 21, suggested Hector should instead “check with the public library or the Catholic Church.”

Red and blue state surprises

The 74’s investigation, which entailed thousands of phone calls between February 2023 and May 2024, revealed striking contrasts and unexpected outcomes in many places throughout the country.

Hector did not receive a single rejection in Iowa, a state whose staunchly Republican governor recently signed into law a Texas-style rule allowing police to arrest the undocumented. The law, which will take effect in July, makes it a crime to enter the state after a deportation. Yet seven of the nine high schools we queried accepted our newcomer — and two said they would likely enroll him.

He also fared well in deep-red Wyoming, Nebraska and South Dakota.

Likewise, four of five schools in Missouri accepted our student despite state Republicans’ effort to implement strict deportation orders and effectively bar undocumented students from college.

Results were quite different among California, Texas, Florida and New York, where more than half — 37.5 million — of the nation’s roughly 64 million Hispanic residents live. Hector was turned away far more often than he was admitted in those states: The 74 registered 65 refusals and 33 acceptances among them.

While those “noes” might be expected in often hard-right Texas and Florida, Hector was roundly rejected in progressive California, with 33 of 35 schools denying him and two others likely to refuse him.

California is home to more undocumented immigrants than any other state in the union, and has taken far-reaching measures to shield residents from deportation. Yet it provides no protection for general education students who wish to enroll in high school past the state’s compulsory attendance age of 18.

Schools in New York, where a former state attorney general sued the Utica City School District in 2015 for shunting refugees into inferior programs, broke with the pack: 23 accepted Hector while five denied him.

In Illinois, he was rejected at 25 high schools — out of 32 total — including seven in Chicago, a city that has publicly welcomed new arrivals.

Though they are both located in the Southwest and have roughly the same percentage of Hispanic residents, Nevada (30.3%) and Arizona (32.5%) diverged greatly in their responses.

Arizona, home to former Maricopa County sheriff Joe Arpaio, whose 24-year reign of terror against immigrants led to a criminal conviction and a controversial presidential pardon, was far more welcoming to Hector than its neighbor. This, despite the Grand Canyon State’s recent push to allow landowners to shoot and kill those who illegally cross the border from Mexico.

Only 1 in 16 Nevada high schools admitted our student but he was permitted to enroll at 6 of 18 Arizona schools — and would likely be accepted at one more.

When registration is random

Almost all 50 states and D.C. have laws establishing a maximum age for public school enrollment. But The 74’s investigation revealed they are often disregarded on the ground.

While Hector was turned away from 204 schools where he had a right to attend according to his age, he was accepted at 31 schools where state statute would have allowed staffers to refuse him for that same reason.

The 74 found that for newcomers, enrollment is haphazard. School personnel at every level seemed unaware of state regulations or misinformed about the specifics. In addition, in some states, the statutes are less than straightforward. Many local employees expressed confusion on the issue or said their district or county set its own rules.

State-By-State Enrollment Regulations By Age

| Alabama | “Every child between the ages of six and 17 years shall be required to attend a public school, private school, church school, or be instructed by a competent private tutor.” |

| Alaska | A student is considered school age until they are 20 |

| Arizona | Between the ages of 6 and 21 |

| Arkansas | Between the ages of 5 and 21 |

| California | There is no specific maximum age, but education code states, “Each person between the ages of 6 and 18 years … is subject to compulsory full-time education.” |

| Colorado | Younger than 21 |

| Connecticut | Under 21, but students 19 and older can be placed in “another suitable educational program” if they “cannot acquire a sufficient number of credits for graduation by age twenty-one.” |

| Delaware | Through age 20 |

| Florida | Local districts decide |

| Georgia | 21 |

| Hawaii | 20 |

| Idaho | Between the ages of 5 and 21, but schools can set a maximum age for enrollment |

| Illinois | Until age 21 |

| Indiana | No maximum age, but placement of adult students with limited interrupted formal education is a local decision. |

| Iowa | Between the ages of 5 and 21 |

| Kansas | No maximum age for high school enrollment. A district doesn’t have to take any student over the age of 21 but can if it chooses. |

| Kentucky | Under 21 |

| Louisiana | Local districts decide |

| Maine | An eligible student has not reached age 20 before the start of the school year |

| Maryland | “All individuals who are 5 years old or older and under 21 shall be admitted free of charge to the public schools of this State.” |

| Massachusetts | “Although no Massachusetts law or regulation sets the maximum age for enrollment, G.L. c. 71B, § 1 defines ‘school age child’ as ‘any person of ages three through twenty-one who has not attained a high school diploma or its equivalent.’” |

| Michigan | In general, “students will remain eligible for membership if they were less than 20 as of September 1 of the school year.” |

| Minnesota | Until 21 |

| Mississippi | “The state of Mississippi follows MS 1-3-27 and establishes the age of majority in our state as 21, or if they are otherwise emancipated. Therefore, read together, a student would be allowed to attend school through their age of majority, but is not forced to beyond age 17.” |

| Missouri | Up to age 21 |

| Montana | Locally decided |

| Nebraska | Between the ages of 5 and 21 |

| Nevada | Students may attend a comprehensive public school up until age 21, or may attend an “Adult High School program from 18 years to any age older.” |

| New Hampshire | Until 21 |

| New Jersey | Through 20 |

| New Mexico | Under 22 |

| New York | Under 21 |

| North Carolina | Under 21 |

| North Dakota | The child has not reached age 21 before Aug. 1 of the year of enrollment. |

| Ohio | Under 22 |

| Oklahoma | “All children between the ages of five (5) years on or before September 1, and twenty-one (21) years on or before September 1, shall be entitled to attend school free of charge in the district in which they reside.” |

| Oregon | Local decision |

| Pennsylvania | 21 |

| Rhode Island | “There is no maximum school age under Rhode Island law. Thus, whether to enroll a student without any disability who is over eighteen (18) years of age is left to the discretion of the local school district.” |

| South Carolina | Students ages 3–21 enrolling in South Carolina public schools must be allowed to do so at all grade levels. Adult Education is a viable option for some students 17 and over, but students must fully understand that they have the right to enroll in public high school if they choose to do so. |

| South Dakota | 21 |

| Tennessee | There is no age limit for public schools in Tennessee. However, school districts are given latitude to determine student assignment or placement. |

| Texas | “A person who, on the first day of September of any school year, is at least five years of age and under 21 years of age, or is at least 21 years of age and under 26 years of age and is admitted by a school district to complete the requirements for a high school diploma is entitled to the benefits of the available school fund for that year.” |

| Utah | “A student cannot enroll in a Utah public school if they are over age 18 or they have already earned a diploma.” |

| Vermont | “There is not a firm age limit on a student that can attend high school. Yes, a student can pursue their degree at any age, this is not specifically outlined in statute.” |

| Virginia | “‘Person of school age’ means a person who will have reached his fifth birthday on or before September 30 of the school year and who has not reached twenty years of age on or before August 1 of the school year.” |

| Washington | Less than 21 |

| West Virginia | “The West Virginia Department of Education has typically given guidance to counties that they use age 21 as the age cut-off. State Board Policy 2800 defines ‘School-Aged Student’ as follows: Students between the ages of three and 21, provided students have not yet turned 21 years of age prior to September 1.” |

| Wisconsin | Between ages 4 and 20 |

| Wyoming | Up to 21 |

| D.C. | There is no maximum age, but “migrant students have the right to pursue high school studies until the age of 21.” |

Source: State regulations and state education officials.

In some cases, they gave contradictory answers inside the same school.

After checking with her boss, a staffer at Harry S. Truman High School in Levittown, Pennsylvania, accepted Hector in May 2023.

An administrative assistant in student services called back more than a week later to categorically deny him.

“I don’t even know if a school would accept him at age 19, but we only register up to 18,” Helene Hodoba said. “I’m not even sure who you can contact. But I do know for a fact they would have to be 18 to register, not 19.”

Pennsylvania regulations state that students can remain in high school until they graduate or reach the age of 21. A state department of education spokesman confirmed that a 19-year-old should be able to attend.

In Delaware, where the maximum age is 20, it was the district homeless and foster care liaison serving Milford High School who said Hector’s enrollment was “not plausible.” The principal then waved him in.

The 74’s responses came from a wide range of personnel. Though the news outlet was unable to determine the positions held by all respondents, they included 160 registrars, 47 counselors, 45 principals, assistant principals, vice principals or associate principals; 61 secretaries and 33 people who worked in “registration.” Twenty were typists or clerks and 24 worked in “enrollment.” Some staffers held multiple titles. For example, a secretary might also be a registrar.

Strom said it is incumbent on schools to clearly state students’ enrollment rights. While it’s helpful to note alternatives, such as adult education, he said, older newcomers must be told they are legally entitled to a public school education in the states where those rights exist.

“They are morally, ethically and legally bound,” he said of school staffers.

Graduation a fear factor

When Monica Venegas arrived in South Carolina alone at age 20, she was able to enroll at R.B. Stall High School in Charleston. She started in 12th grade, completing all four English classes in a single year to meet graduation requirements.

Venegas, now 21, had already earned a high school diploma in Chile and had studied some English there. But she wanted to better speak and understand the language — Justin Bieber song lyrics could get her only so far — and take steps toward college.

After graduating in May 2023, the aspiring ESL teacher took five courses at Charleston Southern University in the fall on a partial scholarship. She recently halted her studies so she could work at McDonald’s to pay for more schooling.

The soft-spoken young woman said high school was critical to her success in America.

“If I didn’t go to high school, I don’t think I could go to college,” she said on a sunny April afternoon.

Venegas’s trajectory is not the path envisioned by the hundreds of school staffers who turned Hector away, or tried to. Alanys Zacarias, 22 and from Venezuela, said she was met with the far more common response — rejection — when she attempted to enroll in Goose Creek High School, also in South Carolina, when she was 18.

“The person told me no, that I was, I don’t know, I was too old, but he just broke my heart when he said no,” said Zacarias, who now works at a Walmart and in a factory that manufactures high-end pans.

Goose Creek is less than eight miles away from the school that accepted Venegas. A school spokeswoman said Goose Creek complies with state admissions requirements and had no comment on Zacarias’s statement. Goose Creek “is home to one of our more diverse student bodies,” she added, and that staff there were experienced “in working with international and multilingual students and families on enrollment and completion of high school.”

Our test student was admitted at five high schools and turned down at four others in that state, where students can legally remain in school until 21. Two other high schools there indicated they would probably refuse him.

South Carolina schools are obligated to enroll newcomers even if they graduated from high school in another country, something that other states, including Colorado, do not allow. In New Jersey, such students can enroll if their diploma does not meet state standards.

For our test student, a 19-year-old whose high school education was cut short after ninth grade, the reasons most often — and most emphatically stated — for turning him away were his age and inability to graduate “on time.”

“When they come here only for a year or two and then they leave, they are considered a dropout for us, and that goes against us on our state report, which is a big thing,” explained Tina Martinez, the registrar at Guymon High School in Oklahoma who refused to enroll Hector even though students in her state can stay on until 21.

Martinez was not alone in citing her high school’s graduation rate as a concern. Several other school representatives said the same in part because federal K-12 education law mandates that states identify all high schools where the graduation rate dips below 67% for comprehensive support and improvement. Individual states have their own, additional remediation measures.

Guymon High School, where 79% of students are Hispanic and 76% are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch, had an overall 73% four-year graduation rate in 2022. The number dropped to 58% for English learners. Nationally, English learners had a 71% high school graduation rate vs. 86% for all students in 2019-20, according to the most recent federal data.

“There is no legal basis that the expected graduation date would affect the requirement to provide education up to age 21 … It’s a recognition that education has inherent value, not just the value that having the diploma offers.”

Wyoming Department of Education

Boals, who founded a multilingual learners consortium called WIDA at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said graduation should not be a mandate placed on any student’s enrollment. In fact, he said, many who go through the system don’t obtain diplomas.

“But we don’t look at them in ninth grade and say, ‘I don’t think you’re going to make it all the way in four years and get a diploma, so let’s just kick you out right now because this is a waste of your time,’” he said. “You want kids to learn whatever they can learn when they’re within the age of being able to learn.”

The Wyoming Department of Education agreed, as did officials in Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts and New Mexico.

“There is no legal basis that the expected graduation date would affect the requirement to provide education up to age 21,” the Wyoming department said in a statement. “The legal requirement is to provide education, not to provide education only if we expect that the student will complete certain milestones. It’s a recognition that education has inherent value, not just the value that having the diploma offers.”

Newcomer students motivated to attend understand that value — and the lifelong consequences of failing to graduate. Several other immigrant students who enrolled in high school in their late teens or early 20s told The 74 the experience was vital to building their future in the U.S.

One, Diego Vila Peña, said he was the only 18-year-old in his ninth-grade class in suburban Houston in 2017.

It was a tough transition: He had nearly completed 12th grade in Cuba but didn’t speak a word of English and knew nothing about life in America. He struggled, at first, to fit in. But he persevered — and excelled.

He was soon moved to Advanced Placement classes and eventually graduated magna cum laude from Texas State University in San Marcos last year. With a bachelor’s in psychology, he’s contemplating pursuing a graduate degree in cognitive neuroscience therapy or linguistics.

“High school changed everything for me,” Vila Peña said. “I don’t know what I would be, the person I would be, if I had not gone to high school or stayed on top of my education.”

Strom, of Re-imagining Migration, said not only does high school allow for a focus on English language development, it’s where students acquire the soft skills they need in every area in life, including the workforce.

“The social interactions matter so, so much,” he said. “Schools are places where belonging begins. We want to make sure that young people are able to acculturate and integrate into society because our future depends on it.”

But many schools did not share that perspective. A staffer at Centennial High School in Pueblo, Colorado, for example, agreed to enroll our test student, but added, “I don’t see how it would benefit him.”

Likewise, Frontier High School in Red Rock, Oklahoma, admitted Hector, but principal Lori Cooksey warned it “might not do a bit of good.”

A counselor at Central High School in Omaha, Nebraska, questioned Hector’s motives for wanting an education at all before accepting him.

“So, essentially, you are just using us to learn English,” Julie Politi said.

Tough hurdles and unusual restrictions

Schools across the country, in considering Hector’s enrollment, erected barriers that seemed to restrict access.

Montgomery Blair High School in Silver Spring, Maryland, accepted our student but noted it could not proceed with registration without a letter from the minister of education in Venezuela. Similarly, John Handley High School in Winchester, Virginia, said Hector’s enrollment depended in part on that country’s compulsory education laws.

Darren Heslep, principal at Green River High School in Green River, Wyoming, accepted Hector but said that “he wouldn’t get to participate in extracurriculars.”

Many school staffers, including the principal at Colorado High School Charter, Osage Campus, warned her school might not be a solid choice for a student just learning the language.

“He’s going to walk into fully English-speaking classes,” Elizabeth Feldhusen said.

Jared Wang, vice principal at Caldwell High School in Caldwell, Idaho, said he would accept Hector, but would not place him in some core classes.

“There’s a lot of classes he wouldn’t be able to take,” Wang said. “I mean, I don’t know if we could give him a complete full schedule. We could put him in some EL classes, some study skills classes, maybe like a math class, science, but there’s a lot of classes he wouldn’t be able to, you know, succeed in, seeing as he doesn’t speak any English. We wouldn’t put him in an English class or a history class.”

Under federal law, public schools must ensure that English learners can “participate meaningfully and equally in educational programs,” receive appropriate language assistance services to become proficient in English, have access to grade-level curricula so they can be promoted and graduate and be able to take part in all aspects of school life, academic and extracurricular.

Boals said schools can’t simply refuse to teach English learners core subjects.

“That’s straight up illegal,” he said.

A stubborn focus on immigration status

A staffer at East High School in Rockford, Illinois, said their school would not enroll Hector if he had a visitor’s visa. Another, at Laramie High School in Wyoming went further, insinuating Hector’s request for enrollment was somehow tied to his citizenship application.

“We don’t do anything with visas,” registrar Pam Fisher said, unprompted. “We don’t have a way to get those so a student can apply for the F-1 [nonimmigrant student visa]. Is he here on a tourist visa? Is he a citizen?”

I just have to wonder why they are asking this. How does it influence their view of the child? What are they doing with this information?

Carol Salva, education consultant

Staffers at Alliance High School in Nebraska and Lebanon High School in New Hampshire also asked about Hector’s immigration status with the Alliance employee persisting long after she was told such information could not be used to determine enrollment.

“We need to know,” said secretary Shardel Nelson. “Is he a U.S. citizen?”

Staff at Habersham Central High School in Georgia said that if Hector was seeking asylum, they would want copies of that paperwork. Evelyn Soto, an administrative assistant at Eastern Carver County Schools in Chaska, Minnesota, was concerned with Hector’s citizenship — and with who was going to pay for his education.

“Since his parents are not here and he wasn’t born here, he might need to pay tuition,” she said.

Carol Salva, a national education consultant with expertise in serving newcomer students whose education was cut short, called this a terrible move.

“I just have to wonder why they are asking this,” she said. “How does it influence their view of the child? What are they doing with this information? We should be focusing on what students bring to our community and what assets we can leverage.”

Rare welcomes

While a Passaic High School employee refused our student, saying he was unlikely to graduate before aging out, another New Jersey school just 2.4 miles away in Clifton had an entirely different approach to older newcomers.

Jory Samkoff, ELL specialist and student services liaison, was sure Hector could enroll there, adding, “we encourage them to max out their time at Clifton” before they pursue a GED.

A staffer at Sammamish High School in Bellevue, Washington, was even more encouraging.

“It might be good for him to get acclimated to the school and, in case he can’t finish out, we can still get him connected with different programs or different options for him to try and complete a high school diploma elsewhere,” said registrar Esmeralda Bailon.

Samantha Hardy, registrar at High School South in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, felt the same, even if Hector could not graduate “on time.”

“Go ahead and start the registration,” she said. “We will educate him until we can’t.”

Grandview High School’s registrar in Missouri, was equally enthusiastic. “You absolutely can get him in this year,” she said in April 2023. “He probably won’t get any credit but could come here and get the lay of the land.”

Denison High School in Iowa was also accommodating.

“I can’t always guarantee they will get a high school diploma,” principal Dave Wiebers said, speaking of similar students. “I can guarantee he could come to school, take classes and learn.”

Bellows Free Academy in Vermont, after accepting our newcomer, was proud to offer him more than just academics.

“We have clubs and sports and all of these things,” registrar Martina Newell noted. “It might be a good experience for him to come.”

A Muhlenberg School District staffer in Reading, Pennsylvania, went even further, welcoming Hector not just to the school — but to the country.

“First of all, I’m glad he’s here,” said Zachariah Milch, director of clinical services. “He’s got, hopefully, a nice, long, beautiful and successful life ahead of him here. We’re going to help him any way we can.”

The American spirit

Child immigrants to this country face many perils, reaching far beyond school enrollment. Pulitzer Prize-winning reporting by Hannah Dreier in The New York Times last year revealed that many are made to work dangerous jobs on construction sites and farm fields, in factories and slaughterhouses. Dreier’s stories exposed how companies, preying upon their desperation, flout child labor laws and jeopardize young workers’ health and safety.

Even outside this particularly vulnerable group, hundreds of thousands of children, including those born in America, have gone missing from school. The Associated Press’s Bianca Vázquez Toness and Sharon Lurye, as part of their award-winning reporting, showed how these students’ lives — and education — were upended by the pandemic. One Georgia family was kept out of the classroom for years because of onerous paperwork demands.

All these students are linked by the same circumstance: They are unable to access the free K-12 public education to which they are entitled.

For many, the outcome is bleak. Studies show that young people who do not obtain a high school diploma are more likely to be sick, die young and become incarcerated or unemployed than their better-educated peers. And they earn less than half the median weekly salary of those who obtain a bachelor’s.

Given the poorly understood and often ignored patchwork of state regulations governing maximum enrollment age, advocates say federal guidance would be helpful.

“A uniform national standard defined in policy, and potentially in legislation, could be a transformative step, benefiting parents, students and school personnel,” Strom noted.

But, like many others, Strom fears such a move is impossible in our current political climate. What’s more achievable, he and other advocates said, is to change the rules around enrollment so schools are not penalized for accepting older students.

To that end, some argue for giving English learners more time to graduate as is already done for students with disabilities, who can stay in high school until 21 if needed.

“The first thing that must happen is that federal and state guidelines that give these students a right to their education must not penalize the very districts that are supporting them by ‘dinging’ them because they don’t finish in four years,” said Pamela Broussard, a national leader in English learners’ education who has taught in the Houston area for decades.

Alerting these students to their rights and giving them the flexibility they need to meet their academic goals are policy decisions that benefit not only new arrivals, advocates said, but the nation as a whole.

“There’s nothing that exemplifies the American dream and the American spirit more than a public education — and the right to receive that public education,” Boals said. “These kids are here. They’re going to either be productive citizens or they’re not.”

Our Responses

The 74 reached out multiple times to all school staffers who were quoted or partially quoted in our story whether we named them or not. In cases where we named the school but did not cite an individual’s comments, we contacted the staffers whose conversations we characterized.

We explained the circumstances of their original exchanges with senior reporter Jo Napolitano and gave everyone an opportunity to explain or expound upon their statements. Most did not respond. Here are those who did:

- The Centennial High School staffer in Pueblo, Colorado, who agreed to enroll our test student, but added, “I don’t see how it would benefit him,” said she would reach out to the district office for a response. We did not hear back.

- Lori Cooksey, principal at Frontier High School in Red Rock, Oklahoma, admitted our student but said enrollment “might not do a bit of good.” She acknowledged her comment, asked for a follow-up email explaining our story and said she would forward it to the school’s attorney for consideration. We supplied the email but did not hear back.

- A Montgomery Blair High School spokeswoman in Silver Spring, Maryland, where a staffer accepted our student but noted he could not proceed with registration without a letter from the minister of education in Venezuela, thanked us for our work and said communications staff would reach out. We did not hear back.

- Through a district spokesperson, a John Handley High School staffer in Winchester, Virginia, denied saying that enrollment depended, in part, on Venezuela’s compulsory education laws. When told that The 74 has a recording of the February 6, 2024, conversation, the spokesperson said the information shared by the staffer was “incorrect and not the practice that John Handley High School, nor Winchester Public Schools, follows as it relates to (English Learner) EL student enrollment.” She said that process includes “meeting with the student and their family with an interpreter present if needed, reviewing the student’s previous transcripts, providing mandatory screening for English Learner services, and developing a timeline for high school completion.” She also cited several data points from the 2023-24 school year: “19% of the John Handley High School population are identified as ELs, 5% of these students are over the age of 18 [and] 78% of these students were born outside of the United States, hailing from 30 different countries.”

- Jim Karedes, principal of Delavan-Darien High School in Wisconsin, who said, “To be explicit, it’s going to be a waste of time,” and, “He is 100% going to be a dropout,” said we did not have permission to use his name, the district’s name or any identifiable information in our report. The 74 does not need permission, however, to report the facts of the conversation with Karedes.

- A Harry S. Truman High School staffer in Levittown, Pennsylvania, accepted Hector in May 2023. But another district employee, Helene Hodoba, called back more than a week later to deny him. In a voicemail responding to our request for comment, Hodoba said that her school accepts general education students up until their 18th birthday. She said exceptions can be made for students with disabilities or those who speak English as a second language — but she did not offer that when posed with registering Hector.

- Tina Martinez, the registrar at Guymon High School in Oklahoma who refused to enroll Hector because he would be considered a dropout which “goes against us on our state report,” said she had no comment when reached by phone.

- Julie Politi, the Central High School counselor in Omaha, Nebraska, who questioned Hector’s motives for wanting an education, saying, “So, essentially, you are just using us to learn English?” did not add anything to her comments when reached by phone or in subsequent emails.

- Jared Wang, Caldwell High School vice principal in Caldwell, Idaho, said he would accept Hector, but would not place him in some core classes because he did not speak English. He later wrote, via email, that he did not recall our conversation (The 74 has a recording of Wang’s October 12, 2023, conversation and our story quotes verbatim from that recording) and that newcomers are, in fact, enrolled in core classes at his school, contradicting his earlier statement.

- The East High School staffer in Rockford, Illinois, who said the school would not enroll Hector if he had a visitor’s visa, denied making that statement. The 74 has transcribed notes from the April 19, 2023, conversation and the article’s description of that conversation accurately reflects the transcription. She later added in a follow-up communication: “RPS [Rockford Public Schools] regularly enrolls and welcomes newcomers from all over the world” and that “citizenship is not asked about during enrollment.”

- Jory Samkoff, Clifton Public Schools ELL specialist in New Jersey, was sure Hector could enroll at her high school, adding, “Usually, we encourage them to max out their time at Clifton” before they pursue a GED. She said she was honored by our story’s recognition.

- Esmeralda Bailon, Sammamish High School registrar in Bellevue, Washington, said our student was welcomed to enroll and that “in case he can’t finish out, we can still get him connected with different programs … for him to try and complete a high school diploma elsewhere.” She said she was glad that her school’s enrollment experience was an inviting one but “saddened to hear that this wasn’t the case with some of the other schools you reached out to.”

- Zachariah Milch, the Muhlenberg School District’s director of clinical services in Reading, Pennsylvania, who said he hoped Hector would go on to have “a nice, long, beautiful and successful life ahead of him here,” thanked The 74 for shining a light on the challenges young immigrants often face in this country.

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter