How Federal COVID Aid Is Uplifting English Learners in This Small Rhode Island City

Central Falls, where nearly half of students are English learners, offers 2 extra hours of language instruction daily. That adds up to roughly 50 days

Central Falls, Rhode Island

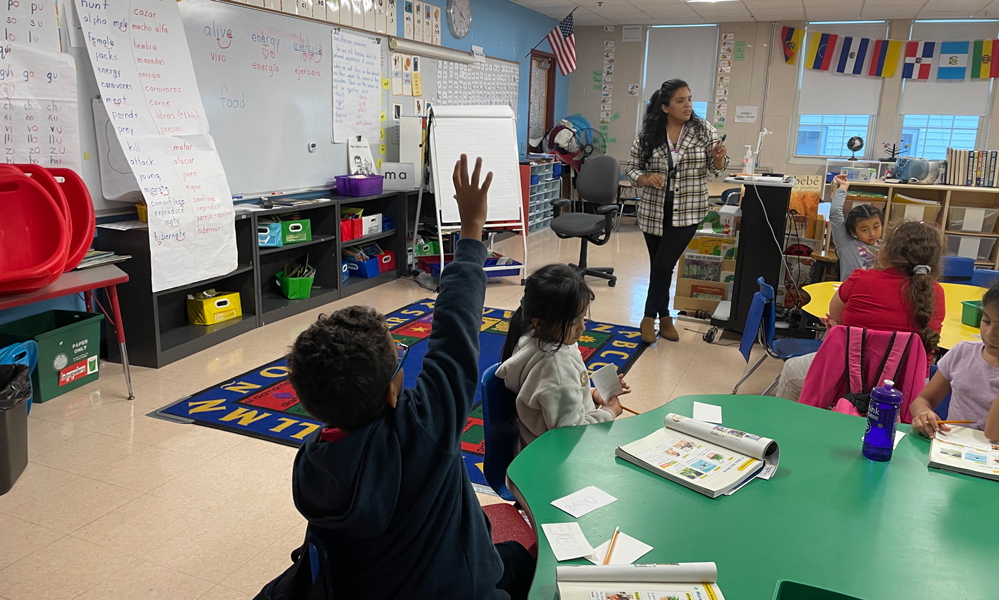

It’s 3:45 p.m., an hour since the final bell rang at Ella Risk Elementary School, but Patricia Montalvo’s classroom is still full.

She points to the white board, prompting the class of third and fourth graders — many of whom immigrated to the country within the last year — to read a word that’s broken down by syllable: ex | er | cise.

Hands shoot into the air and Montalvo cues them to read together. Voices echo through the classroom, but most pronounce the last syllable with a short vowel, “siz” instead of “size.” The teacher, who herself grew up in nearby Providence after moving from Bolivia when she was 3, reminds her students that the last letter is a “bossy E” that makes the “i” say its name.

“Exer-cise.” She exaggerates the last syllable and lets the class repeat her pronunciation. “What’s exercise?”

“When you work out,” a student offers.

“Ejercicio,” another calls out, providing the Spanish translation.

“In Spanish it’s ‘ejercicio,’ ” Montalvo nods. “Did you guys do exercises today?” Her class had just come from their recreation period. “What did you do?”

“Play with balloons,” a young boy responds. “It was taking a lot of energy,” he adds, smiling as he manages to incorporate another piece of vocabulary, “energy,” from the whiteboard.

This lesson is exactly the sort of English-learning opportunity Central Falls parents have been requesting for years. Now, thanks to pandemic stimulus funding, the district has finally been able to deliver — and leaders hope the programs can close long-standing achievement gaps between English learners and native speakers.

More than a third of the city’s residents were born in another country and some 45% of the school system’s 2,900 students are classified as multilingual learners.

There’s a “clear discrepancy,” Superintendent Stephanie Toledo said, between the testing outcomes of students who are proficient in English versus those who are not, and English learners perennially lag behind.

But in the pandemic’s aftermath, Central Falls has gotten the chance to reimagine its programming with $23 million in federal grant money — its share of the unprecedented $190 billion nationwide for K-12 education delivered through three COVID stimulus packages.

For decades, state officials have considered Central Falls among Rhode Island’s most challenged school systems. The per capita income of the one-square-mile, 22,500-person city is Rhode Island’s lowest, below $18,000 a year, and financial control of the district has been in the state’s hands since the 1990s. In 2010, the district made national headlines when its leadership fired the entire staff of its only high school as part of a federal push to turn around low-performing schools.

With the infusion of COVID funds, leaders recognized the unique opportunity to uplift the school system. They crunched academic data to identify what student investments might deliver the highest impact. About 600 multilingual learners, they found, remained below the minimum English proficiency level to succeed in English-only classes, and many had languished there for years.

Boosting these long-neglected students could address a “root cause” of the district’s years of underperformance, Toledo believed.

“We wanted to focus in on kids who have been with us but are not yet developing in English,” she said.

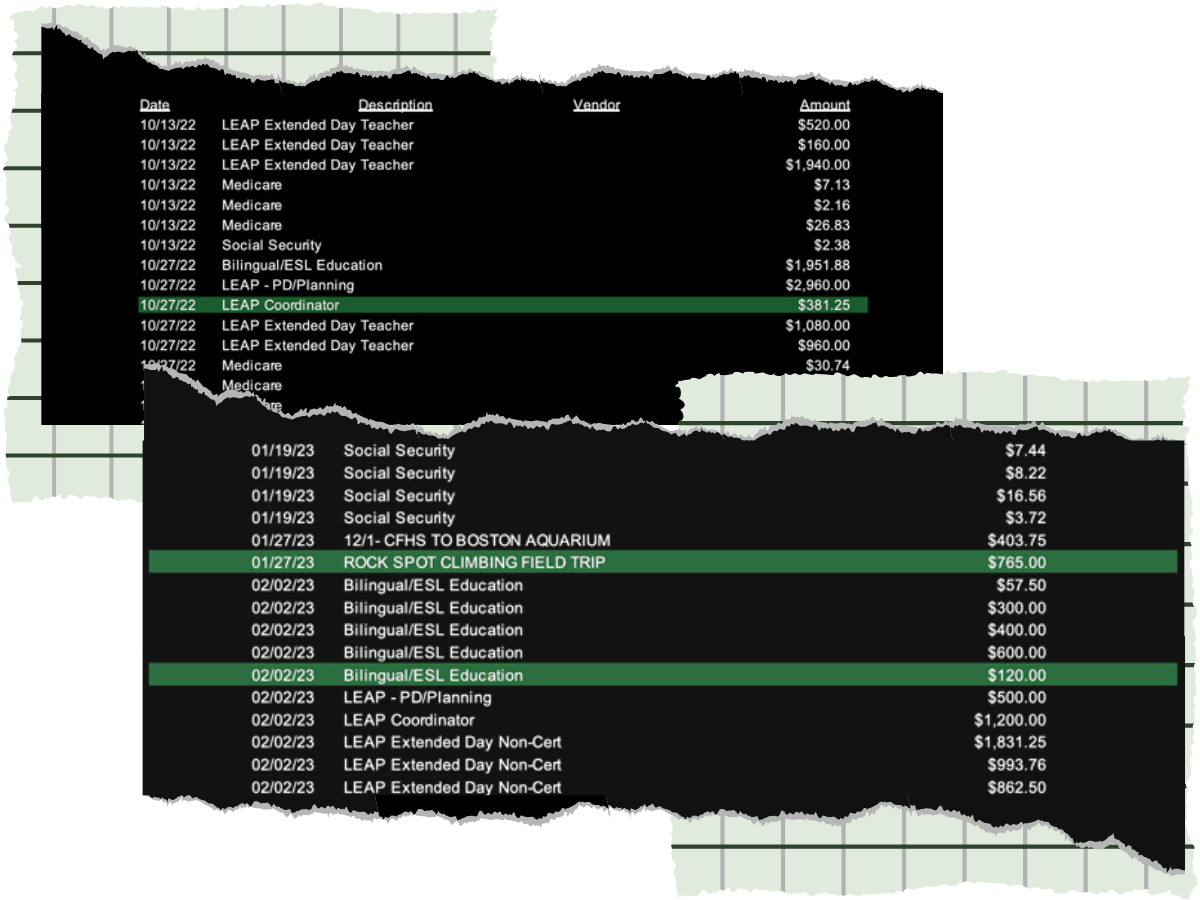

Afterschool language learning academies like the one where Montalvo teaches have become a key component of that new strategy. Research shows longer school days can improve students’ attendance, test scores and emotional development. Since October, some $308,000 has funded programs across all five of the district’s K-12 campuses, according to spending records the district provided to The 74, with $1.4 million devoted to their continuation.

Though the programs are voluntary, more than 225 students have already enrolled, the district said, adding two hours of English learning to their daily schedules. The elementary school offerings are at capacity and have lengthy waitlists. The high school program, where some students work jobs or play sports after school, still has open seats. At full scale, the district says it will be able to serve all 600 English learners that the intervention targets.

It’s the right approach, believes Jannet Sanchez, who works as a guidance counselor for multilingual learners at the high school and coordinates the extended day program there.

“The amount of hours in the day that students get for English acquisition isn’t enough,” she said. The “biggest request” she gets from students and parents is for more language learning opportunities, she said.

Compiled over the course of the year, the afterschool sessions will add roughly 50 extra school-days’ worth of instruction, more than doubling the English-learning time students would likely get otherwise.

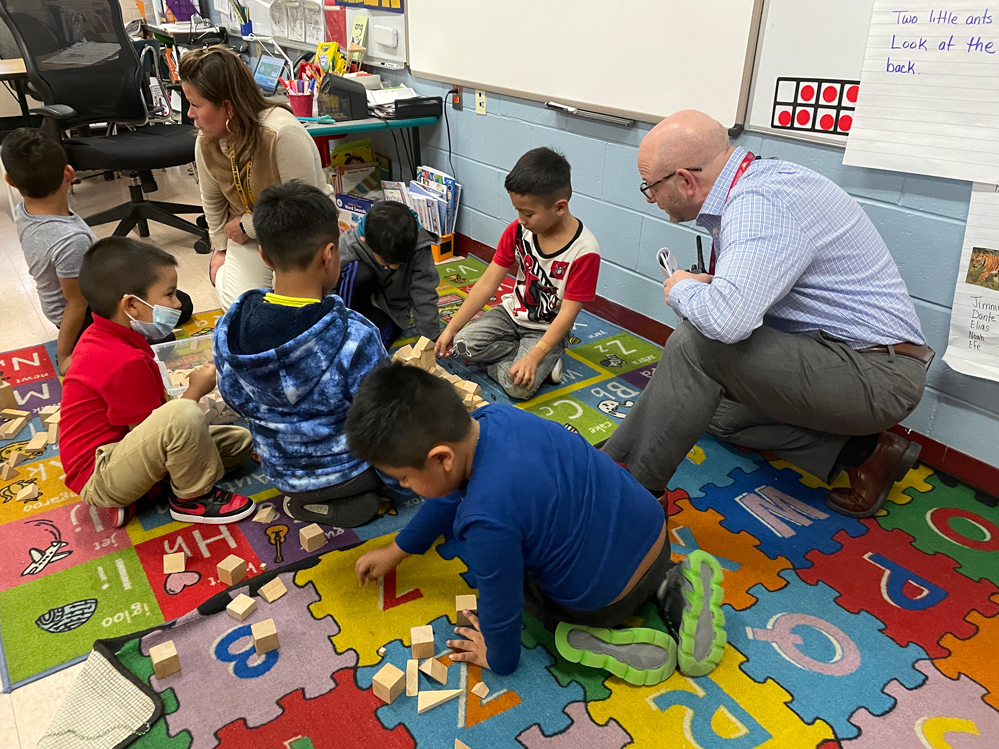

“Two extra hours a day is a lot,” said Buddy Comet, principal of Ella Risk. He had long advocated for a program like the one they now run and is thrilled the new funding makes it possible. “It allowed us to do something I already wanted to do,” he said.

Montalvo, who teaches multilingual learners both during the school day and in the afterschool program, recognizes what makes the afterschool sessions special. In her experience, youth who are still picking up English typically have a “silent stage” while absorbing the language. But in the extended day program, with 10 or fewer students per teacher, youngsters have a safe environment to develop their speaking skills.

The context conveys to students, “Here we’re practicing. Make those mistakes. We’ll practice, we’ll learn and we’ll learn from each other,” Montalvo said.

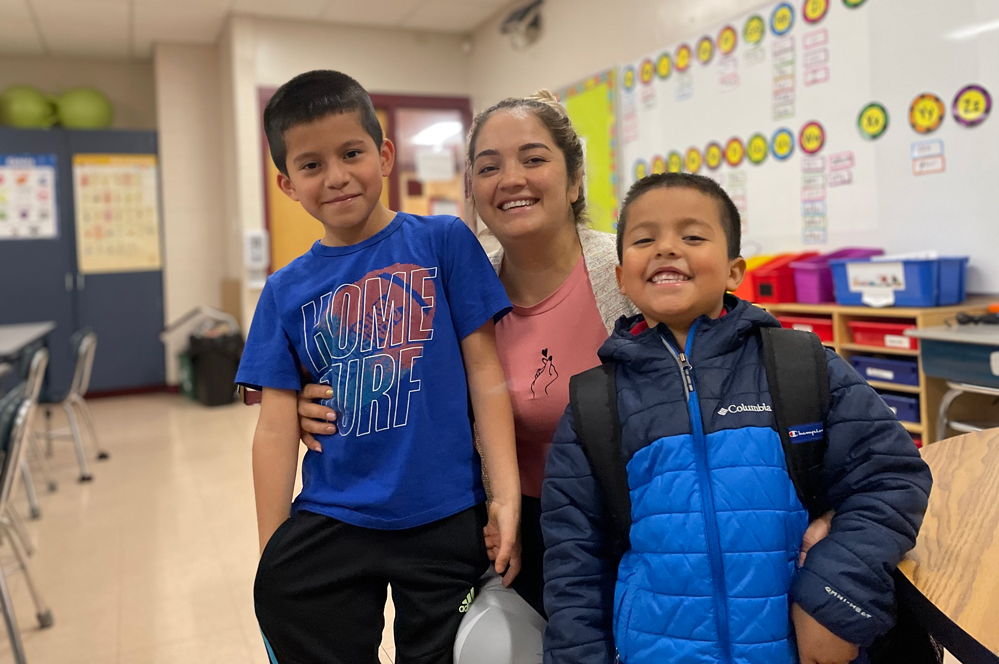

That’s exactly what’s happened for Maribel Gregorio’s son David, who is 5. Speaking through a translator, she told The 74 she enrolled him because he was shy, but the elementary schooler has already “loosened up” and is now “more expressive” in English.

Once when she picked him up early from the program, he cried because he didn’t want to leave, she said.

An investment in equity

The afterschool program consists of three 40-minute blocks: one for speaking, one for reading and one for recreation. Every month or so, the leaders coordinate a field trip. In November, they brought students to watch Lyle Lyle Crocodile. For many, it was their first time ever going to a movie theater. So many friends and family wanted to come that the school had to upgrade to a bigger theater. Students were glued to the film and parents pitched in by forming a spontaneous popcorn-passing brigade, Principal Comet said.

To finance the operation, the district has so far spent roughly $8,000 on field trips, $17,000 on staff professional development, $71,000 on contracts with vendors and $212,000 on employee salaries, according to its expenditure records. Teachers who work at the afterschool program earn $40 per hour plus a stipend to compensate their lesson-planning time. Other afterschool staff such as paraprofessionals can earn $35 or more per hour thanks to overtime pay, Toledo said.

Receiving some $1,000 more in her monthly take-home pay is like “the extra whipped cream on top” for Montalvo. The work in itself is meaningful, she said, but as a teacher who already works long hours, she’s glad for the additional compensation.

Simultaneously, she knows the time also gives a reprieve to working families. “It’s a time for parents to have their kids here until 4:30,” the teacher said. “They can work a little longer.”

The afterschool lessons work in tandem with another new program for English learners — called a “newcomer academy” — which operates during school hours. Recently arrived immigrant children learning English alternate between bilingual classes and general education classes, meaning they get the chance to both learn in their native language and also be integrated with their English-speaking classmates.

Now in its second year, the results have been immediate and dramatic. At Ella Risk, where the newcomer academy operates, multilingual learners outperformed their native English-speaking peers on the most recent state exams and had proficiency rates five times the state average for that group, Superintendent Toledo said, adding that the results “thrilled” her.

It’s too soon for quantitative outcomes from the extended day program, which launched just months ago. But Principal Comet already sees students’ growth. One of his main goals is to build students’ speaking abilities, an area where his multilingual learners have struggled on tests, historically. Classroom by classroom, the school leader sees students’ newfound confidence.

As Comet walks into a new classroom where youngsters are playing with blocks, the principal is met with calls of, “Look!” as kids motion for him to see their block structures.

On his way over, a student pulls the principal aside to deliver a message and grins to reveal a gap in his smile.

“My tooth go out.”

Bumpy progress

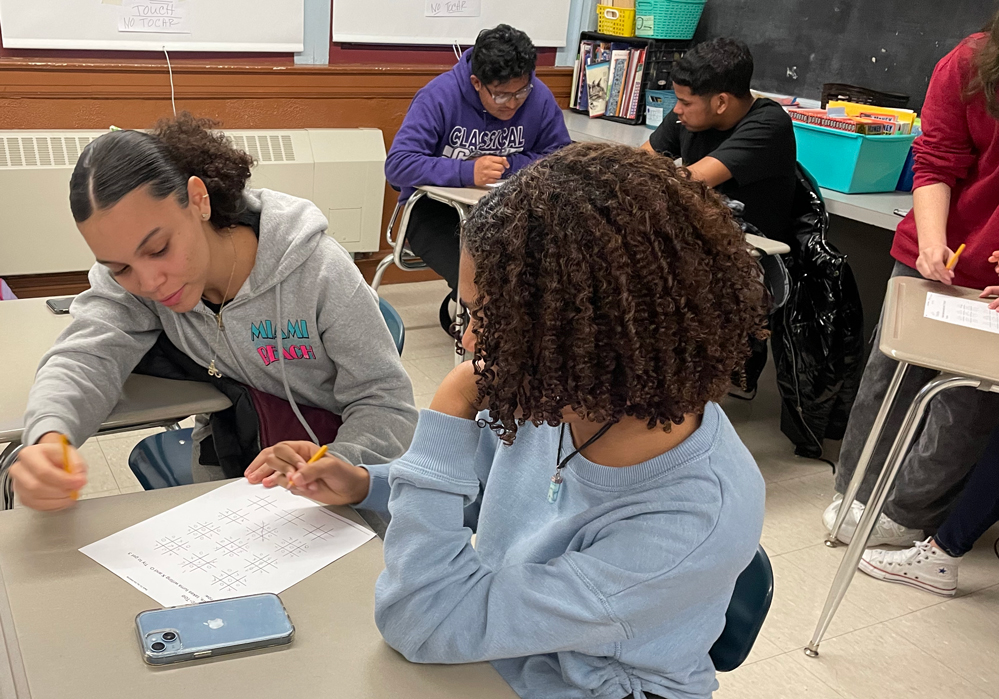

The scene is more tempered at the high school, where about two dozen students stay for afterschool lessons one late November afternoon.

In one classroom, students take turns reading aloud from a graphic novel. Most mumble, and several scroll on their phone or whisper among themselves while the teacher’s attention is elsewhere. When it’s time for a written reflection, the instructor resorts to begging.

“It’s no stress, write.” She walks from table to table pointing at the students’ worksheets, which sit mostly empty. “Even if it’s one sentence. One word.”

Next door in Jessica Olarte’s classroom, the vibe is more upbeat. She teaches multilingual learners during the school day and now leads a dozen students in a game of Kahoot, quizzing them on English vocabulary and grammar. Students are unable to contain themselves and yell out when they know the answer. One names his avatar “The Best” and Olarte puts the nickname in ironic air quotes every time she reads the leaderboard. She appreciates the casualness of her time in the afterschool program.

“It’s not too strict. Like if they want to check with their Snapchat or their Instagram, go ahead. It’s not school.” It helps teachers “connect a little more” with their students, she said.

But the energy level is not the only difference between her classroom and the one next door. Olarte is the only instructor at the high school program whose racial and linguistic identities match the majority of her students. She is Hispanic and grew up in Pawtucket, the city that borders Central Falls. Meanwhile, the other teachers are white and monolingual.

Research shows that educators of color and those who speak multiple languages improve outcomes for all students, but provide a particular boost to students who share the same identity. Central Falls has invested in helping its teaching assistants, who are predominantly Hispanic, earn their bachelor’s degrees and teaching licenses, but the process takes several years.

Teacher diversity — or lack thereof — is “something I wish would change over time,” said Montalvo, who, aside from several paraprofessionals, was also the only Spanish-speaking teacher at the Ella Risk extended day program.

“When you have that background of, you’re undocumented, you’re from the same culture, you understand the social cues.”

Even for the handful of youth who speak Portuguese, not Spanish, Olarte makes an effort to learn some of their language as well as teach them English.

Stacy Lopes is one such student. The high school senior moved to Central Falls four months ago from the Cape Verde islands off the west coast of Africa. She’s clear why she spends the two extra hours after school each day.

“I want to learn English because I’m going to college and I will need it,” she said, looking up from a game of tic tac toe during recreation period.

Marvin Hernandez Trinidad shares her motivation. The 12th grader moved from Mexico a year ago and intends to go to college for engineering. He is “happy” during the afterschool lessons because he learns new English words, he said.

Montalvo, who works with the elementary schoolers, reminds young people of any age to take pride in their native tongue as they hone their skills in new one.

“Being bilingual is their superpower,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter