Indiana Joins States Mandating the Science of Reading in Classrooms

Legislators say a reading “crisis” also requires banning other ways of teaching reading

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Indiana has joined a rising tide of states mandating phonics-based science of reading lessons, banning schools from using balanced literacy and other strategies that rely on context clues and pictures.

Under a series of bills signed Thursday by Governor Eric Holcomb, schools will have to use reading curriculum approved by the Indiana Department of Education as following the phonics-based science of reading by fall of 2024.

Teachers will have to take training in the science of reading before earning or renewing teaching licenses. And teacher training programs in the state will need to teach that method within a few years or lose accreditation.

The state is also banning schools from teaching students “three-cueing” strategies — in which students take cues from pictures or context to guess at words — that are part of the whole language and balanced literacy teaching approaches that have been popular the last few decades.

The Indiana changes come as some legislators say the state is having a reading “crisis.”

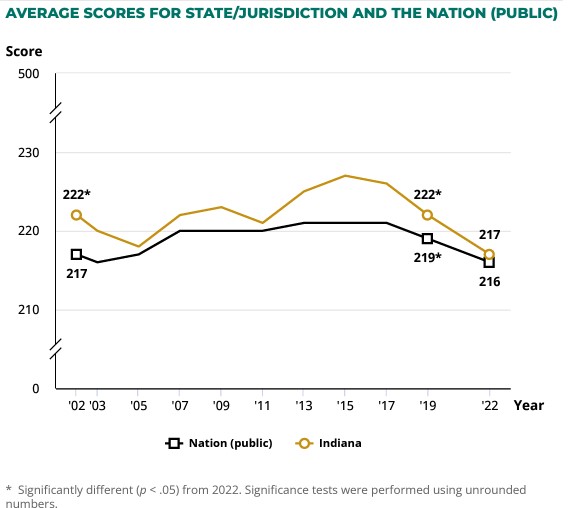

Passage rates on the foundational reading portion of IREAD-3, the state’s third grade reading tests, are down 10 percentage points from their 2014 peak of around 91 percent to 81 percent today. Indiana has seen a similar decline in 4th grade reading scores on the “Nation’s Report Card,” the National Assessment of Education Progress. Indiana scores peaked in 2015, but declined in 2017 and again in 2019, before falling further in 2022 after the pandemic.

Indiana’s average 4th grade NAEP reading score in 2022, however, was a hair above the national average, 217 to 216.

Still, Holcomb and the Indiana Department of Education call for raising the passage rate on IREAD-3 from 81 percent today to 95 percent by 2027.

The cueing strategies have a bullseye on them in several states this spring. Though only Arkansas and Louisiana had banned them before this year, at least eight other states, including neighboring Ohio, are looking at laws eliminating them.

Republican state Sen. Aaron Freeman, who co-sponsored a key bill in the change in the Indiana Senate, called it the most important issue before the legislature this year, other than the state budget.

“It’s critically important for children to read and we’ve got to give teachers in schools the proper tools to teach kids to read,” said Freeman. “I have no idea why we got off track and why we went down a different road. But it’s very clear to me that we’re on the wrong course and we’ve got to course correct here very quickly.”

Rep. Bob Behning, chairman of the House Committee on Education, said the change should help all students, especially poor students, in all subjects once they are able to read and understand lessons better.

“I do believe it is a potential game changer all the way around,” said Behning, a Republican.

The changes had little opposition as they were debated, but leaders in the minority Democratic party had reservations about making a move so fast after never seeing any bills about the science of reading in prior years.

Democratic House Minority Leader Shelli Yoder called prohibiting other methods of teaching “heavy handed” and “tyrannical,” even if well-intentioned.

“If we’ve done one thing it is to communicate to teachers that we do not trust your profession, and we’re gonna micromanage it,” Yoder said. “And we’re going to make sure that you use this one method of teaching reading. That does create a bit of a pause for me.”

Though teachers next door in Ohio have made the same complaint as Yoder, Indiana’s two large teachers unions, the Indiana State Teachers Association and American Federation of Teachers Indiana, have not made the ban a major issue. They have been mostly supportive of the shift, as have state associations of school boards, principals and urban schools.

And while the state will ban schools from using cueing as part of its official curriculum, Behning said there’s no real way for the state to prevent or penalize teachers from using it on their own.

“We don’t have any cueing police,” he said.

With Holcomb’s approval of the shift last week, he joined West Virginia Governor Jim Justice, who signed a similar bill in March. Florida’s legislature has passed similar changes, which are still waiting for the governor’s signature.

Ohio, as well as Texas, have had similar bills pass one legislative house, but not both yet.

The shift to science of reading will be paid for from a $111 million fund created late last year by the state and the Lilly Endowment Inc., a philanthropy created by the family that founded the Eli Lilly and Co. Fortune 500 pharmaceutical company. The Endowment, which is independent of the Indianapolis-based company, donated $60 million to K-12 science of reading efforts and $25 million to teacher preparation programs, while the state has chipped in $26 million from the state’s federal COVID relief dollars.

The state’s new budget bill adds up to $20 million in each of the next two years for Department of Education efforts on science of reading.

Another bill that pushes science of reading signed last week allows districts to apply for grants from the department for literacy coaches, textbooks and lessons, teacher and administrator training or giving students extra reading help with tutoring or summer programs..

The bills also call for:

- Ordering the state Department of Education to make all state learning standards and tests match science of reading, while eliminating any references to cueing.

- Creating extra help and requirements for all elementary schools in which less than 70% of third graders pass the state third grade reading test, including having a literacy coach in the school for two years, partially paid by the state and Lilly. About ¼ of the state’s 1,050 elementary schools would be affected.

- Ordering teacher preparation programs to start teaching science of reading. The Department of Education will start reviewing these programs by the 2024-25 school year and pull accreditation for those not moving toward teaching it well.

- Calls for salary increases for teachers who have had literacy training, on top of the stipends of up to $1,200 the Lilly donation is already paying as they take it.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter