A Cautionary AI Tale: Why IBM’s Dazzling Watson Supercomputer Made a Lousy Tutor

With a new race underway to create the next teaching chatbot, IBM’s abandoned 5-year, $100M ed push offers lessons about AI’s promise and its limits.

By Greg Toppo | April 9, 2024With a new race underway to create the next teaching chatbot, IBM’s abandoned 5-year, $100M ed push offers lessons about AI’s promise and its limits.

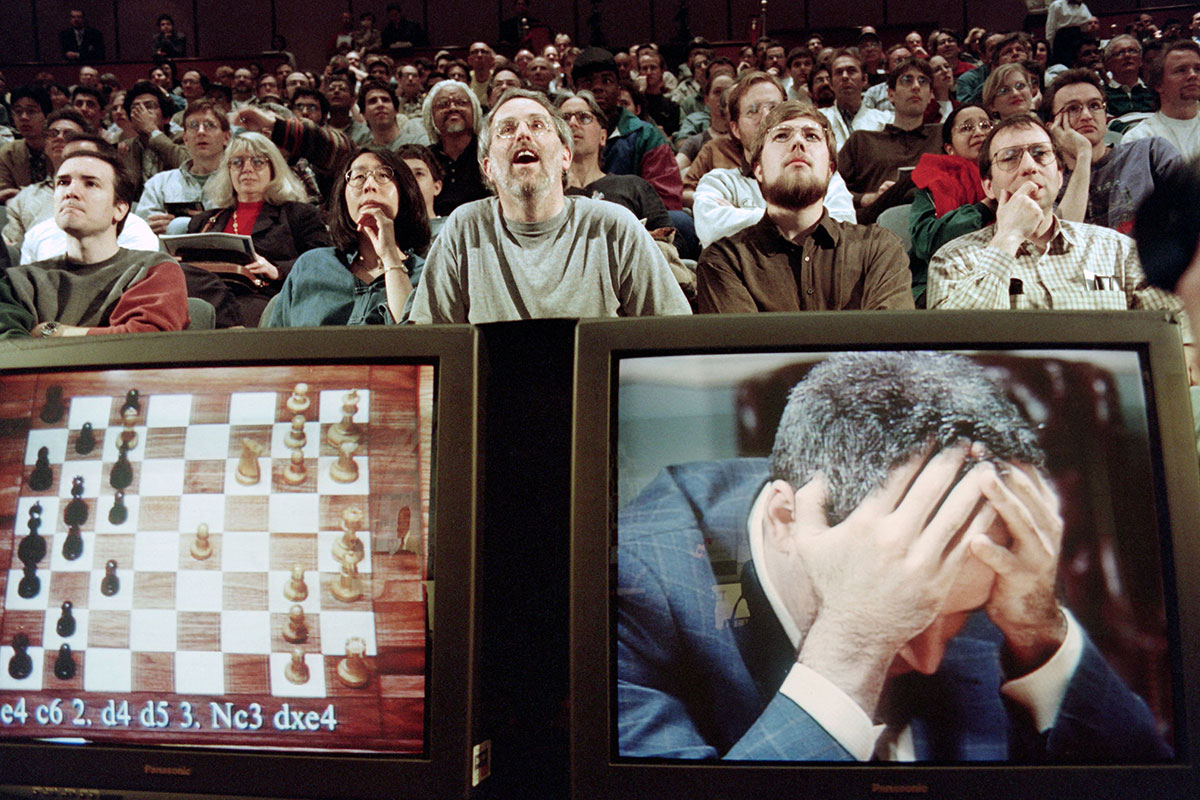

In the annals of artificial intelligence, Feb. 16, 2011, was a watershed moment.

That day, IBM’s Watson supercomputer finished off a three-game shellacking of Jeopardy! champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. Trailing by over $30,000, Jennings, now the show’s host, wrote out his Final Jeopardy answer in mock resignation: “I, for one, welcome our computer overlords.”

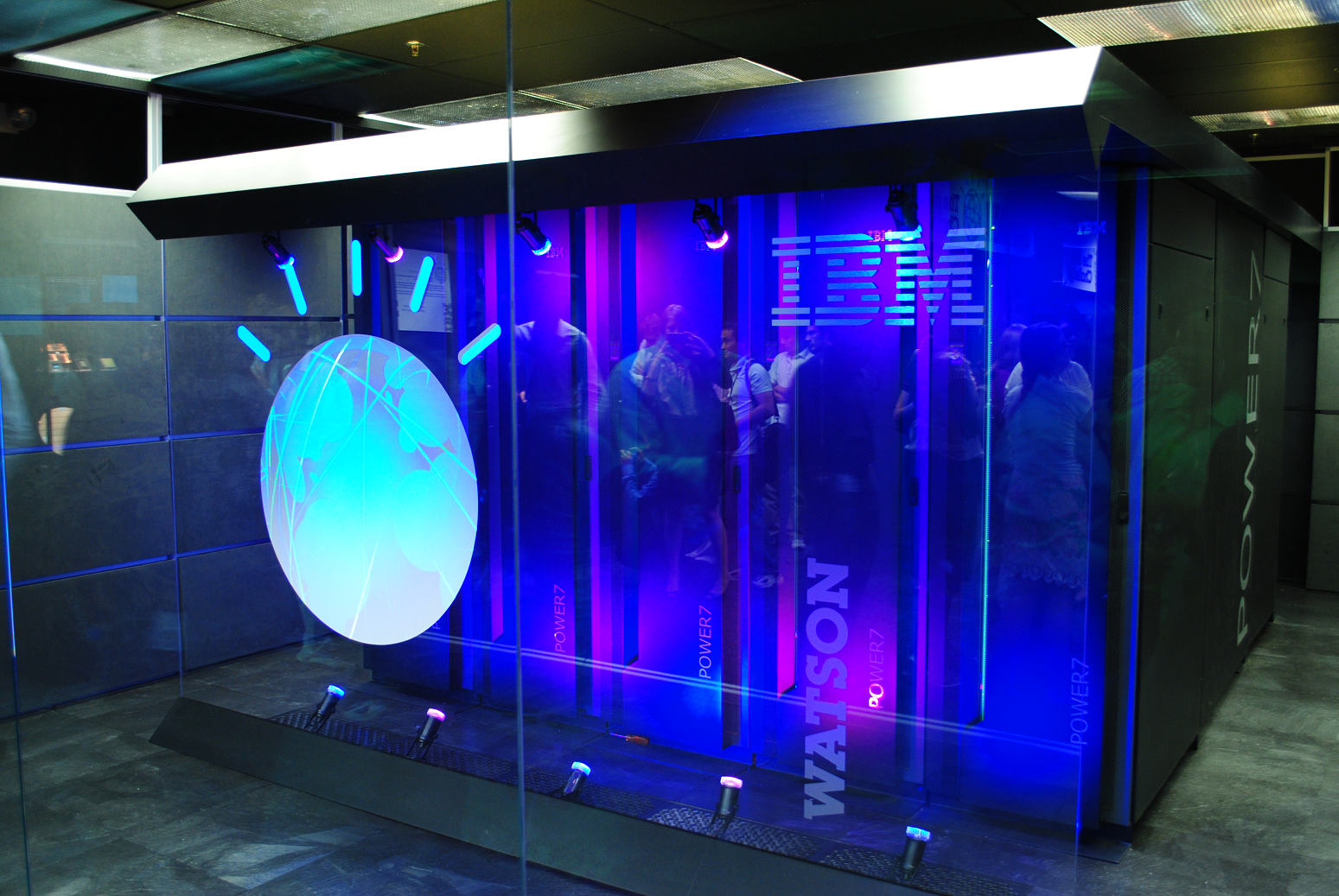

A lark to some, the experience galvanized Satya Nitta, a longtime computer researcher at IBM’s Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York. Tasked with figuring out how to apply the supercomputer’s powers to education, he soon envisioned tackling ed tech’s most sought-after challenge: the world’s first tutoring system driven by artificial intelligence. It would offer truly personalized instruction to any child with a laptop — no human required.

“I felt that they’re ready to do something very grand in the space,” he said in an interview.

Nitta persuaded his bosses to throw more than $100 million at the effort, bringing together 130 technologists, including 30 to 40 Ph.D.s, across research labs on four continents.

But by 2017, the tutoring moonshot was essentially dead, and Nitta had concluded that effective, long-term, one-on-one tutoring is “a terrible use of AI — and that remains today.”

For all its jaw-dropping power, Watson the computer overlord was a weak teacher. It couldn’t engage or motivate kids, inspire them to reach new heights or even keep them focused on the material — all qualities of the best mentors.

It’s a finding with some resonance to our current moment of AI-inspired doomscrolling about the future of humanity in a world of ascendant machines. “There are some things AI is actually very good for,” Nitta said, “but it’s not great as a replacement for humans.”

His five-year journey to essentially a dead-end could also prove instructive as ChatGPT and other programs like it fuel a renewed, multimillion-dollar experiment to, in essence, prove him wrong.

Some of the leading lights of ed tech, from Google to Microsoft, are trying to pick up where Watson left off, offering AI tools that promise to help teach students. Sal Khan, founder of Khan Academy, last year said AI has the potential to bring “probably the biggest positive transformation” that education has ever seen. He wants to give “every student on the planet an artificially intelligent but amazing personal tutor.”

A 25-year journey

To be sure, research on high-dosage, one-on-one, in-person tutoring is unequivocal: It’s one of the most powerful interventions available, offering significant improvement in students’ academic performance, particularly in subjects like math, reading and writing.

But traditional tutoring is also “breathtakingly expensive and hard to scale,” said Paige Johnson, a vice president of education at Microsoft. One school district in West Texas, for example, recently spent more than $5.6 million in federal pandemic relief funds to tutor 6,000 students. The expense, Johnson said, puts it out of reach for most parents and school districts.

We missed something important. At the heart of education, at the heart of any learning, is engagement.

Satya Nitta, IBM Research’s former global head of AI solutions for learning

For IBM, the opportunity to rebalance the equation in kids’ favor was hard to resist.

The Watson lab is legendary in the computer science field, with six Nobel laureates and six Turing Award winners among its ranks. It’s where modern speech recognition was invented, and home to countless other innovations such as barcodes and the magnetic stripes on credit cards that make ATMs possible. It’s also where, in 1997, Deep Blue beat world chess champion Garry Kasparov, essentially inventing the notion that AI could “think” like a person.

The heady atmosphere, Nitta recalled, inspired “a very deep responsibility to do something significant and not something trivial.”

Within a few years of Watson’s victory, Nitta, who had arrived in 2000 as a chip technologist, rose to become IBM Research’s global head of AI solutions for learning. For the Watson project, he said, “I was just given a very open-ended responsibility: Take Watson and do something with it in education.”

Nitta spent a year simply reading up on how learning works. He studied cognitive science, neuroscience and the decades-long history of “intelligent tutoring systems” in academia. Foremost in his reading list was the research of Stanford neuroscientist Vinod Menon, who’d put elementary schoolers through a 12-week math tutoring session, collecting before-and-after scans of their brains using an MRI. Tutoring, he found, produced nothing less than an increase in neural connectivity.

Nitta returned to his bosses with the idea of an AI-powered cognitive tutor. “There’s something I can do here that’s very compelling,” he recalled saying, “that can broadly transform learning itself. But it’s a 25-year journey. It’s not a two-, three-, four-year journey.”

IBM drafted two of the highest-profile partners possible in education: the children’s media powerhouse Sesame Workshop and Pearson, the international publisher.

One product Sesame envisioned was a voice-activated Elmo doll that would serve as a kind of digital tutoring companion, interacting fully with children. Through brief conversations, it would assess their skills and provide spoken responses to help kids advance.

Meanwhile, Pearson promised that it could soon allow college students to “dialogue with Watson in real time.”

Nitta’s team began designing lessons and putting them in front of students — both in classrooms and in the lab. In order to nurture a back-and-forth between student and machine, they didn’t simply present kids with multiple-choice questions, instead asking them to write responses in their own words.

It didn’t go well.

Some students engaged with the chatbot, Nitta said. “Other students were just saying, ‘IDK’ [I don’t know]. So they simply weren’t responding.” Even those who did began giving shorter and shorter answers.

Nitta and his team concluded that a cold reality lay at the heart of the problem: For all its power, Watson was not very engaging. Perhaps as a result, it also showed “little to no discernible impact” on learning. It wasn’t just dull; it was ineffective.

“Human conversation is very rich,” he said. “In the back and forth between two people, I’m watching the evolution of your own worldview.” The tutor influences the student — and vice versa. “There’s this very shared understanding of the evolution of discourse that’s very profound, actually. I just don’t know how you can do that with a soulless bot. And I’m a guy who works in AI.”

When students’ usage time dropped, “we had to be very honest about that,” Nitta said. “And so we basically started saying, ‘OK, I don’t think this is actually correct. I don’t think this idea — that an intelligent tutoring system will tutor all kids, everywhere, all the time — is correct.”

‘We missed something important’

IBM soon switched gears, debuting another crowd-pleasing Watson variation — this time, a touching throwback: It engaged in Oxford-style debates. In a televised demonstration in 2019, it went up against debate champ Harish Natarajan on the topic “Should we subsidize preschools?” Among its arguments for funding, the supercomputer offered, without a whiff of irony, that good preschools can prevent “future crime.” Its current iteration, Watsonx, focuses on helping businesses build AI applications like “intelligent customer care.”

Nitta left IBM, eventually taking several colleagues with him to create a startup called Merlyn Mind. It uses voice-activated AI to safely help teachers do workaday tasks such as updating digital gradebooks, opening PowerPoint presentations and emailing students and parents.

Thirteen years after Watson’s stratospheric Jeopardy! victory and more than one year into the Age of ChatGPT, Nitta’s expectations about AI couldn’t be more down-to-earth: His AI powers what’s basically “a carefully designed assistant” to fit into the flow of a teacher’s day.

To be sure, AI can do sophisticated things such as generating quizzes from a class reading and editing student writing. But the idea that a machine or a chatbot can actually teach as a human can, he said, represents “a profound misunderstanding of what AI is actually capable of.”

Nitta, who still holds deep respect for the Watson lab, admits, “We missed something important. At the heart of education, at the heart of any learning, is engagement. And that’s kind of the Holy Grail.”

These notions aren’t news to those who do tutoring for a living. Varsity Tutors, which offers live and online tutoring in 500 school districts, relies on AI to power a lesson plan creator that helps personalize instruction. But when it comes to the actual tutoring, humans deliver it, said Anthony Salcito, chief institution officer at Nerdy, which operates Varsity.

”The AI isn’t far enough along yet to do things like facial recognition and understanding of student focus,” said Salcito, who spent 15 years at Microsoft, most of them as vice president of worldwide education. “One of the things that we hear from teachers is that the students love their tutors. I’m not sure we’re at a point where students are going to love an AI agent.”

Students love their tutors. I'm not sure we're at a point where students are going to love an AI agent.

Anthony Salcito, Nerdy

The No. 1 factor in a student’s tutoring success is simply showing up consistently, research suggests. As smart and efficient as an AI chatbot might be, it’s an open question whether most students, especially struggling ones, would show up for an inanimate agent or develop a sense of respect for its time.

When Salcito thinks about what AI bots now do in education, he’s not impressed. Most, he said, “aren’t going far enough to really rethink how learning can take place.” They end up simply as fast, spiffed-up search engines.

In most cases, he said, the power of one-on-one, in-person tutoring often emerges as students begin to develop more honesty about their abilities, advocate for themselves and, in a word, demand more of school. “In the classroom, a student may say they understand a problem. But they come clean to the tutor, where they expose, ‘Hey, I need help.’”

Cognitive science suggests that for students who aren’t motivated or who are uncertain about a topic, only one-on-one attention will help. That requires a focused, caring human, watching carefully, asking tons of questions and reading students’ cues.

Jeremy Roschelle, a learning scientist and an executive director of Digital Promise, a federally funded research center, said usage with most ed tech products tends to drop off. “Kids get a little bored with it. It’s not unique to tutors. There’s a newness factor for students. They want the next new thing.”

There's a newness factor for students. They want the next new thing.

Jeremy Roschelle, Digital Promise

Even now, Nitta points out, research shows that big commercial AI applications don’t seem to hold users’ attention as well as top entertainment and social media sites like YouTube, Instagram and TikTok. One recent analysis dubbed the user engagement of sites like ChatGPT “lackluster,” finding that the proportion of monthly active users who engage with them in a single day was only about 14%, suggesting that such sites aren’t very “sticky” for most users.

For social media sites, by contrast, it’s between 60% and 65%.

One notable AI exception: Character.ai, an app that allows users to create companions of their own among figures from history and fiction and chat with the likes of Socrates and Bart Simpson. It has a stickiness score of 41%.

As startups like Synthesis offer “your child’s superhuman tutor,” starting at $29 per month, and Khan Academy publicly tests its popular Khanmigo AI tool, Nitta maintains that there’s little evidence from learning science that, absent a strong outside motivation, people will spend enough time with a chatbot to master a topic.

“We are a very deeply social species,” said Nitta, “and we learn from each other.”

IBM declined to comment on its work in AI and education, as did Sesame Workshop. A Pearson spokesman said that since last fall it has been beta-testing AI study tools keyed to its e-textbooks, among other efforts, with plans this spring to expand the number of titles covered.

Getting ‘unstuck’

IBM’s experiences notwithstanding, the search for an AI tutor has continued apace, this time with more players than just a legacy research lab in suburban New York. Using the latest affordances of so-called large language models, or LLMs, technologists at Khan Academy believe they are finally making the first halting steps in the direction of an effective AI tutor.

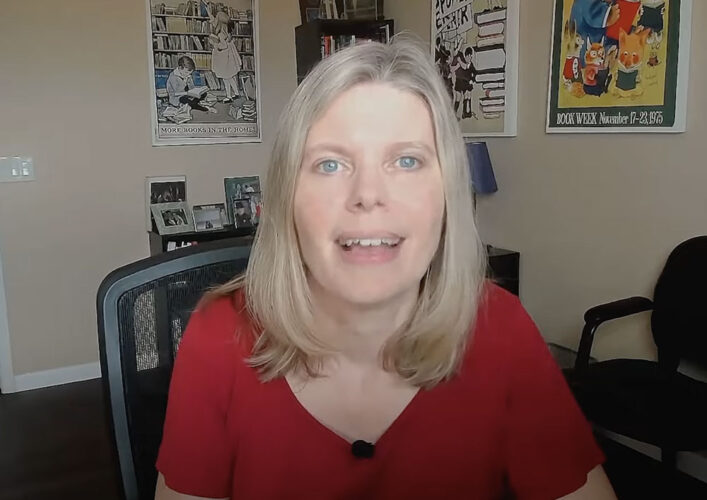

Kristen DiCerbo remembers the moment her mind began to change about AI.

It was September 2022, and she’d only been at Khan Academy for a year-and-a-half when she and founder Khan got access to a beta version of ChatGPT. Open AI, ChatGPT’s creator, had asked Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates for more funding, but he told them not to come back until the chatbot could pass an Advanced Placement biology exam.

So Open AI queried Khan for sample AP biology questions. He and DiCerbo said they’d help in exchange for a peek at the bot — and a chance to work with the startup. They were among the first people outside of Open AI to get their hands on GPT-4, the LLM that powers the upgraded version of ChatGPT. They were able to test out the AI and, in the process, become amateur AI prompt engineers before anyone had even heard of the term.

Like many users typing in queries in those first heady days, the pair initially just marveled at the sophistication of the tool and its ability to return what felt, for all the world, like personalized answers. With DiCerbo working from her home in Phoenix and Khan from the nonprofit’s Silicon Valley office, they traded messages via Slack.

“We spent a couple of days just going back and forth, Sal and I, going, ‘Oh my gosh, look what we did! Oh my gosh, look what it’s saying — this is crazy!’” she told an audience during a recent appearance at the University of Notre Dame.

She recounted asking the AI to help write a mystery story in which shoes go missing in an apartment complex. In the back of her mind, DiCerbo said, she planned to make a dog the shoe thief, but didn’t reveal that to ChatGPT. “I started writing it, and it did the reveal,” she recalled. “It knew that I was thinking it was going to be a dog that did this, from just the little clues I was planting along the way.”

More tellingly, it seemed to do something Watson never could: have engaging conversations with students.

DiCerbo recounted talking to a high school student they were working with who told them about an interaction she’d had with ChatGPT around The Great Gatsby. She asked it about F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous green light across the bay, which scholars have long interpreted as symbolizing Jay Gatsby’s out-of-reach hopes and dreams.

“It comes back to her and asks, ‘Do you have hopes and dreams just out of reach?’” DiCerbo recalled. “It had this whole conversation” with the student.

The pair soon tore up their 2023 plans for Khan Academy.

It was a stunning turn of events for DiCerbo, a Ph.D. educational psychologist and former senior Pearson research scientist who had spent more than a year on the failed Watson project. In 2016, Pearson had predicted that Watson would soon be able to chat with college students in real time to guide them in their studies. But it was DiCerbo’s teammates, about 20 colleagues, who had to actually train the supercomputer on thousands of student-generated answers to questions from textbooks — and tempt instructors to rate those answers.

Like Nitta, DiCerbo recalled that at first things went well. They found a natural science textbook with a large user base and set Watson to work. “You would ask it a couple of questions and it would seem like it was doing what we wanted to,” answering student questions via text.

But invariably if a student’s question strayed from what the computer expected, she said, “it wouldn’t know how to answer that. It had no ability to freeform-answer questions, or it would do so in ways that didn’t make any sense.”

After more than a year of labor, she realized, “I had never seen the ‘OK, this is going to work’ version” of the hoped-for tutor. “I was always at the ‘OK, I hope the next version’s better.’”

But when she got a taste of ChatGPT, DiCerbo immediately saw that, even in beta form, the new bot was different. Using software that quickly predicted the most likely next word in any conversation, ChatGPT was able to engage with its human counterpart in what seemed like a personal way.

Since its debut in March 2023, Khanmigo has turned heads with what many users say is a helpful, easy-to-use, natural language interface, though a few users have pointed out that it sometimes gets math facts wrong.

Surprisingly, DiCerbo doesn’t consider the popular chatbot a full-time tutor. As sophisticated as AI might now be in motivating students to, for instance, try again when they make a mistake, “It’s not a human,” she said. “It’s also not their friend.”

(AI's) not a human. It’s also not their friend.

Kristen DiCerbo, Khan Academy

Khan Academy’s research shows their tool is effective with as little as 30 minutes of practice and feedback per week. But even as many startups promise the equivalent of a one-on-one human tutor, DiCerbo cautions that 30 minutes is not going to produce miracles. Khanmigo, she said, “is not a solution that’s going to replace a human in your life,” she said. “It’s a tool in your toolbox that can help you get unstuck.”

‘A couple of million years of human evolution’

For his part, Nitta says that for all the progress in AI, he’s not persuaded that we’re any closer to a real-live tutor that would offer long-term help to most students. If anything, Khanmigo and probabilistic tools like it may prove to be effective “homework helpers.” But that’s where he draws the line.

“I have no problem calling it that, but don’t call it a tutor,” he said. “You’re trying to endow it with human-like capabilities when there are none.”

Unlike humans, who will typically do their best to respond genuinely to a question, the way AI bots work —by digesting pre-existing texts and other information to come up with responses that seem human — is akin to a “statistical illusion,” writes Harvard Business School Professor Karim Lakhani. “They’ve just been well-trained by humans to respond to humans.”

Largely because of this, Nitta said, there’s little evidence that a chatbot will continuously engage people as a good human tutor would.

What would change his mind? Several years of research by an independent third party showing that tools like Khanmigo actually make a difference on a large scale — something that doesn’t exist yet.

DiCerbo also maintains her hard-won skepticism. She knows all about the halting early decades of computers a century ago, when experimental, punch-card operated “teaching machines” guided students through rudimentary multiple-choice lessons, often with simple rewards at the end.

In her talks, DiCerbo urges caution about AI revolutionizing education. As much as anyone, she is aware of the expensive failures that have come before.

In her recent talk at Notre Dame, she did her best to manage expectations of the new AI, which seems so limitless. In one-to-one teaching, she said, there’s an element of humanity “that we have not been able to — and probably should not try — to replicate in artificial intelligence.” In that respect, she’s in agreement with Nitta: Human relationships are key to learning. In the talk, she noted that students who have a person in school who cares about their learning have higher graduation rates.

But still.

ChatGPT now has 100 million weekly users, according to Open AI. That record-fast uptake makes her think “there’s something interesting and sticky about this for people that we haven’t seen in other places.”

Being able to engineer prompts in plain English opens the door for more people, not just engineers, to create tools quickly and iterate on what works, she said. That democratization could mean the difference between another failed undertaking and agile tools that actually deliver at least a version of Watson’s promise.

Seven years after he left IBM to start his new endeavor, Nitta is philosophical about the effort. He takes virtually full responsibility for the failure of the Watson moonshot. In retrospect, even his 25-year timeline for success may have been naive.

“What I didn’t appreciate is, I actually was stepping into a couple of million years of human evolution,” he said. “That’s the thing I didn’t appreciate at the time, which I do in the fullness of time: Mistakes happen at various levels, but this was an important one.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter