NYC Schools Reported Over 9,600 Students to Child Protective Services Since Aug. 2020. Is It the ‘Wrong Tool’ for Families Traumatized by COVID?

By Asher Lehrer-Small | January 27, 2022

Paullette Healy can tick off the ways her family’s life has been plunged into uncertainty and fear over the last three months: Her younger child’s repeated nightmares and increased anxiety, the hours she’s poured into collecting forms from her kids’ doctor and psychiatrist to prove she’s a fit parent and an arduous and probably costly legal process that still looms to clear her name.

From early November through Jan. 1, the Bay Ridge, Brooklyn family was under investigation by the Administration for Children’s Services, or ACS, the New York City agency tasked with looking into suspected cases of child abuse and neglect. Healy had been reported for educational neglect for not sending her children to school amid COVID fears, even though she says her kids kept up with their work remotely.

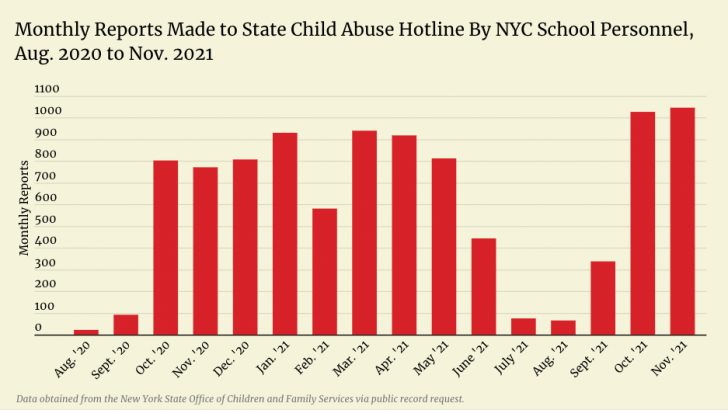

The report that spurred their investigation was one of more than 2,400 that New York City school personnel made to the New York Statewide Central Register for Child Abuse and Maltreatment during the first three months of the 2021-22 school year, according to data obtained by The 74 through a public record request — about 45 percent more than were reported over the same time span a year prior when most of the city’s nearly 1 million students were learning remotely. From August 2020 to November 2021, records show NYC school staff made a total of 9,674 reports.

The highest monthly tally, 1,046, came in November 2021, the same month that ACS and the Department of Education issued joint guidance instructing schools to have patience with families keeping their children home due to COVID-19 concerns, and to avoid jumping to allegations of educational neglect when students don’t show up.

About a third of the reports from NYC school personnel from September through November — 839 out of 2,412 — included an allegation of educational neglect. Of that total, just over half named educational neglect as the sole allegation, according to an ACS spokesperson, who pointed out that the rate was actually higher pre-COVID in the fall of 2019, when about 40 percent of reports from city school personnel alleged educational neglect.

Many of the families caught up in COVID-related investigations this school year, including the Healys, say that given the DOE’s statements and guidance, their ACS reports should never have been made.

Child welfare investigations, which disproportionately involve low-income families of color, can have devastating impacts. Charges can stay on parents’ records for years — even in cases like Healy’s where the agency ultimately found no evidence of neglect. Job prospects in fields like child care and education can be erased. And most dire, children can be separated from their parents — a trauma that studies show is later associated with elevated risks of mental health challenges, incarceration and even early death.

ACS has clarified that, on its own, missing class should not be a reason for educators to suspect neglect. “We are … working together (with the DOE) to make sure that families are not reported to the state’s child abuse hotline solely because of [a] child’s absences from school,” a spokesperson wrote in a Jan. 13 email to The 74, adding that the agency is providing training to professionals working with children on ways to support families without calling the hotline.

But now, after New York City student attendance rates plunged in early January amid surging Omicron cases, and with ongoing debate over how the Adams administration will approach remote learning, questions swirl over whether even more families may get entangled in the child welfare web.

“I’m … worried about who’s going to be asked to answer for the decisions that they made in the wake of Omicron,” said Gabriel Freiman, head of education practices at the legal nonprofit Brooklyn Defenders.

Healy echoed the concern, adding that families who kept children home amid the surge may be “vulnerable to possible investigation.”

How did we get here?

Rewind to the fall: New York City announced that schools would open in-person with no option for remote learning, and Healy was terrified. She had suffered massive personal losses through the pandemic — more than a dozen of her relatives had died of the virus, she said, ranging in age from 36 to 87 — and the Brooklyn mother remained unconvinced that sending her children into crowded buildings was a good idea. She quickly submitted applications for home instruction for both of her kids.

Meanwhile, just before classrooms reopened, the nation’s largest school district made a vow to parents: “The only time ACS will intervene is if there is a clear intent to keep a child from being educated, period,” then-schools Chancellor Meisha Porter said during a September press conference. “We want to work with our families because we recognize what families have been through.”

Even while remote, Healy’s kids were still learning, she said. Both were accessing and submitting coursework via Google Classroom. She had even met with school staff to update both children’s Individualized Education Programs, the plans that spell out their special needs and mandated school services.

“I was in constant contact (with the schools),” Healy said. “All of the things that needed to happen were still happening.”

So it caught Healy off guard when, in early November, an ACS caseworker knocked on her door. The agency had received a report of suspected educational neglect from a staff member at her younger child’s school.

Healy had understood that a visit from ACS was a possibility. As a member of the advocacy group PRESS, Parents for Responsive Equitable Safe Schools, she knew of numerous other parents keeping their children home from school due to coronavirus concerns who had been investigated. She had even put resources together informing parents of their rights when ACS shows up. But her own investigation still took her by surprise. If anything, she was over-involved in her children’s education, she thought, not neglectful.

“I’ve always inserted myself into the schools whether they wanted me there or not,” Healy joked.

Familiar with her rights as a parent, Healy did not let the caseworker inside their house. But despite being armed with strategies to navigate the situation, the visit was jarring to the whole family. After the caseworker left, her 14 year-old son, who has autism, paced back and forth for an hour, worried that the unfamiliar woman would return with law enforcement, Healy said. Her 13 year-old child, who identifies as non-binary, had continued nightmares, fearing they would be taken away from the only home they knew. Even Healy herself couldn’t avoid creeping thoughts of the worst-case scenario.

“You automatically think someone’s here to take my kids away,” she told The 74.

‘ACS is like the police’

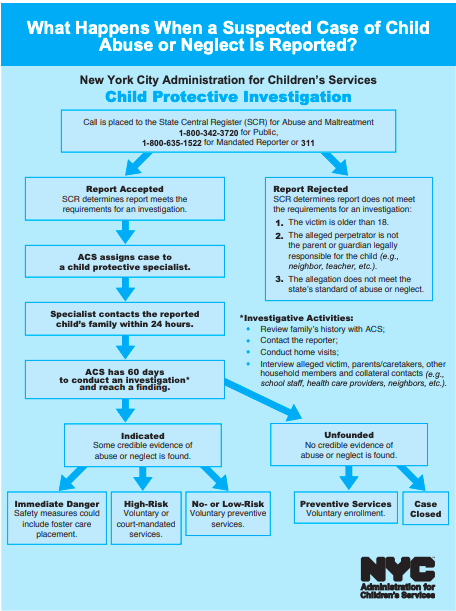

Just like doctors and nurses, school personnel are mandated by New York state law to report suspected cases of child abuse and neglect to a central hotline. But even before COVID-19, experts and parents alike have critiqued the practice as potentially harmful to families and prone to racial bias.

In New York City, some 90 percent of children named in ACS investigations are Black or Hispanic, while, together, those racial groups make up 60 percent of the city’s youth. In 2019, according to city data, the lower-income, mostly Black and Latino neighborhood of East Harlem saw over six times as many investigations as the nearby Upper East Side, which is mostly white and affluent.

Even among neighborhoods with similar poverty rates, those with greater shares of Black and Hispanic residents face higher rates of child welfare investigations, research shows.

“ACS has long been used to criminalize our families,” said Tanesha Grant, a New York City parent leader who formed the group Parents Supporting Parents for mutual aid throughout the pandemic. Many Black parents, she told The 74, see child protective services as a form of racialized surveillance and punishment.

“ACS is a curse word in our community. ACS is like the police,” she said.

“It is deeply concerning to us,” said a spokesperson for the agency, “that, year after year, there are dramatic racial and ethnic disparities in the reports ACS receives from the state and is required [by law] to investigate.”

As per a 2021 state law, mandated reporters are now required to undergo implicit bias training intended to keep reporters’ assumptions from coloring their assessments of parental fitness.

But just how much of an impact it will make in the K-12 setting remains to be seen. Nationwide, school staff report more allegations to child protective services than any other category of reporters, yet school reports are least likely to be substantiated or lead to family interventions, research shows. In New York City, approximately 1 in 3 calls from school personnel ultimately lead to evidence of abuse or neglect, said ACS. In cases where no evidence is found, families often report that the investigation process can be invasive and disturbing.

There’s often a mismatch, said Freiman, of Brooklyn Defenders, between the typical impacts of child protective services investigations and the purpose they are meant to fulfill.

“Neglect is supposed to cover a category below which we don’t expect any parent to go,” the legal expert explained.

But the parents keeping their children out of classrooms this school year, from what he has seen, tend to be highly involved and caring, like Healy. Some are even former PTA heads at their children’s schools.

“These aren’t people who are trying to hurt their children. They’re trying to protect their children,” he told The 74. “ACS is just the wrong tool to employ.”

Even the softer guidance that ACS and DOE offered in November was not enough to sufficiently blunt that tool, advocates said. Healy said she worked with 50 families accused of educational neglect through PRESS and was only able to use the updated guidance to dismiss cases against two of them.

Miranda rights for child welfare

As a way to mitigate some of the worst effects of ACS investigations, state Sen. Jabari Brisport, a former educator from Brooklyn, is sponsoring a bill that would require a Miranda-style reading of parents’ rights at the outset of every child welfare investigation.

“Parents of color are more likely to be unaware of the rights they have when dealing with [child protective services],” Brisport told The 74. “The bill seeks to address the disparities in the CPS system.”

When, without warning, ACS showed up at the door of Melissa Keaton’s Flatbush, Brooklyn apartment in late October, the mother was taken by surprise. Having lost her father, who was a caregiving adult to her 9-year-old daughter, in April 2020 during the city’s deadly first coronavirus wave, Keaton chose not to return her traumatized child to her sought-after dual language school in Manhattan’s Lower East Side when classrooms reopened. The family was not ready for a two-train commute to and from school each day, Keaton decided. Unlike Healy, she was in the dark about how to navigate the interaction with her caseworker.

“There’s no paperwork. There’s no way of, you know, finding out what is this process? How does it work? What is expected of me?” Keaton told The 74.

Parents are not legally obligated to allow caseworkers to enter their homes unless ACS has a warrant. But many parents assent without realizing they have a choice. If caseworkers find evidence of drug use or other outlawed practices, it can lead to compounding charges and increase the likelihood of child separation.

“Sometimes our families actually find themselves in a deeper hole — not because they’ve done anything wrong — but because ACS comes into the home looking for a problem,” said Tajh Sutton, a PRESS organizer. “They’re going through your refrigerator, your cabinets … asking these really invasive and inappropriate questions of your children.”

“This bill doesn’t create new rights,” explained Brisport. “It literally tells parents what their rights are.”

‘ACS should not have been called’

Despite the lasting psychological impacts of the neglect investigation upon her children, Healy also acknowledged that her caseworker was kind and actually quite helpful. The staffer fast-tracked her children’s applications for home instruction, helping her younger child recently gain approval for the program. Healy hopes her son will also soon be approved.

But her example, she believes, is an outlier. Not everyone is so fortunate.

On Dec. 23, Keaton was preparing to lay flowers on the gravestone of her late father. The day marked what would have been his 63rd birthday — and because her dad’s December birthday used to be a part of the family’s holiday rituals, Keaton was feeling his absence even more acutely.

But before she left, she was contacted by her caseworker, who relayed what the mother thought was good news: She was ready to close the case. Keaton told her to come by.

When the caseworker arrived, she told Keaton that the investigation had been completed, but the agency had indeed found evidence of neglect. The news hit her like a thunderclap, Keaton said, stirring fears for how she might appeal, what the findings might mean for her future employment having previously worked at a children’s summer camps, and, most of all, whether it opened the possibility of her daughter being taken away.

The message, Keaton said, was “imprinted in my mind throughout the holidays, along with the thought of, ‘What happens next?’”

The caseworker instructed her to appeal, Keaton said. When pressed on the evidence behind the finding of neglect, Keaton said, the caseworker explained that her daughter’s school had taken weeks to respond to requests, and when they did, they cited her elementary schooler’s inconsistent 2019 summer school attendance as a strike against the family — data that Keaton said is “completely false.”

Staff at the elementary school did not respond to requests for comment and ACS said that it cannot disclose the details of individual cases. Keaton is awaiting paperwork in the mail that will provide insight into the exact reasons the educational neglect allegation was substantiated by ACS.

Keaton believes her case was unproductive at best, and inappropriate at worst. She was trying to keep her daughter safe and had been putting together educational assignments for her despite, she said, not being provided materials by her school. She was also applying for medically necessary home instruction — a process through which the November ACS and DOE joint guidance instructs schools to support parents wary of COVID rather than reporting them to child services.

“Based on the guidelines,” said Keaton, “ACS should not have been called.”

Lead Image: Paullette Healy at the front door with her younger child, Kira. (Asher Lehrer-Small)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter