Report: Schools Won’t Recover from COVID Absenteeism Crisis Until at Least 2030

Dire news from two separate studies require a 'hard pivot,' researchers say — and some lawmakers are starting to listen.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The rate of students chronically missing school got so bad during the pandemic that it will likely be 2030 before classrooms return to pre-COVID norms, a new report says.

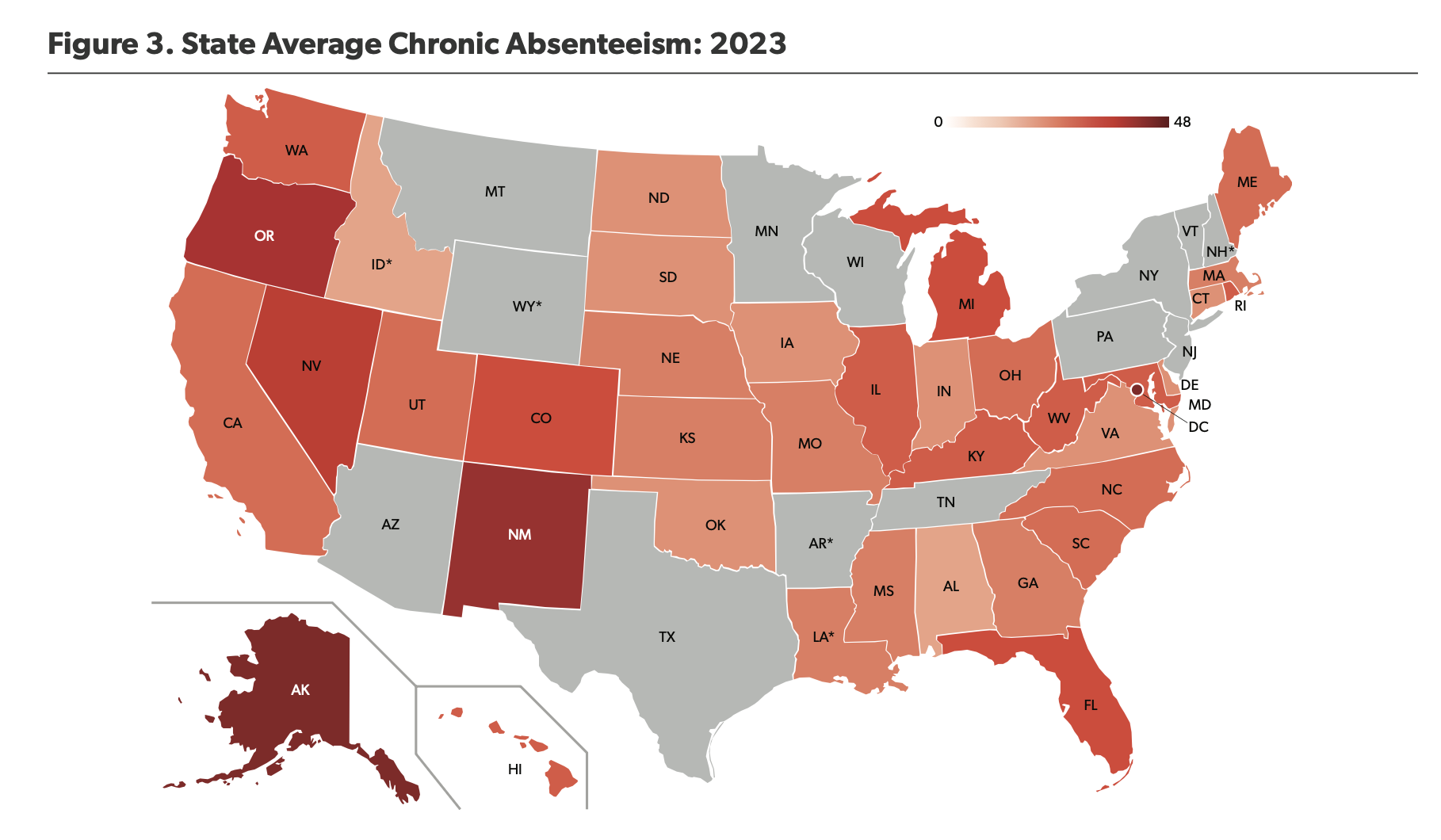

But even that prediction rests on optimistic assumptions about continued improvement in the coming years. For some states, it could take longer. In Louisiana, Oregon and South Carolina, for example, the percentage of students chronically absent for at least 10% of the school year went up in 2022-23, according to the analysis from the American Enterprise Institute.

The report, based on available data from 39 states, calls chronic absenteeism “schools’ greatest post-pandemic challenge.”

“We need to make a hard pivot moving forward,” said Nat Malkus, a senior fellow at the conservative think tank. Minor decreases in chronic absenteeism rates are not enough to stave off “a disaster for the long term” he said, especially in low-performing and high-poverty districts that had serious absenteeism problems before the pandemic.

Malkus, a former middle school teacher, called for districts to make attendance a high priority, especially among elementary educators. Parents, he said, are more likely to respond to messages from children’s teachers than from “a stranger from the school district.”

The report, one of two separate studies of chronic absenteeism released Wednesday, further underscores the enormity of a national crisis that is hindering students’ ability to recover academically from the pandemic. The second analysis shows a substantial increase in the share of districts where at least 30% of students missed 18 or more days of school.

The review of federal data breaks down the rates into five levels of chronic absenteeism, with extreme being the highest.

“We came up with these categories before the pandemic,” said Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works. At that point, nearly 11% of districts nationally had extreme levels. “Then the pandemic hit, and it was like ‘Oh my God.’ ”

By 2021-22, the rate had more than tripled to almost 39%, according to the report, the final installment in a three-part series from Attendance Works and the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University. The data “compels action from state education agencies and policymakers,” researchers wrote.

‘It’s alarming’

Some state lawmakers share that sense of urgency. So far, eight bills in seven states aim to reestablish good attendance habits among the nation’s students.

Earlier this month, a Maryland Senate judicial committee called interim state chief Carey Wright to testify about whether news reports of shockingly high rates in Baltimore — with over half of students repeatedly missing school — were true.

“It’s alarming,” she told the members, after sharing district and state-level data. “We have a lot of children who are chronically absent at very young grades, and that’s a real concern, particularly when you’re thinking that they’re starting their educational career.”

In Maryland, 274 schools out of 1,388 had an extreme chronic absenteeism rate in 2017-18. By 2021-22, that number had reached 700.

Lori Phelps, principal of Woodbridge Elementary in Catonsville, joined Wright to explain how her staff reduced its rate from 28% in 2021-22 to just over 9% in 2022-23.

Identifying patterns that increase absences is part of the answer, she added. For example, students were more likely to miss school on early-release days, so the staff worked with parent leaders to offer an afternoon program on those days. The PTA charged $10, but waived the fee for students with the most absences.

“We all want to prioritize those very important state scores,” Phelps said, “but we made a decision two years ago to prioritize attendance.”

No buses

But even parents determined to get their children to school face significant obstacles if they don’t have transportation. In Colorado, every district has cut bus routes to save money or because of driver shortages, said Michelle Exstrom, education director for the National Conference of State Legislatures. She serves on a state task force expected to propose transportation solutions by the end of the year.

“In rural areas all over the country, where kids don’t have a ride to school, it’s like, duh, they’re not going to be at school,” she said. A lot of parents can’t leave work at 2:30 to pick up their children, she said, and even high school students with cars often can’t drive to school because there’s not enough parking, she said.

In Ohio, two lawmakers think some extra cash might reduce chronic absenteeism in kindergarten and ninth grade, two grade levels with rates around 30%.

The bill, from Democrat Rep. Dani Isaacsohn and Republican Rep. Bill Seitz, would offer $500 annually to families in low-income districts to boost attendance rates in those grades and ideally save money on dropout recovery services in the long run. If the plan passes, it would start as a pilot this fall .

Seitz told The 74 he expects “significant supportive testimony,” based on the success of a similar program led by a philanthropist in Michigan.

Another proposal in Washington, which had a 30% chronic absenteeism rate last year, would provide grants for home visits and tutoring to keep frequently absent high school students on track for graduation. And a Virginia bill would update the definition of “educational neglect” to include a parent’s failure to comply with attendance requirements.

‘Studied in real time’

But both Malkus and Chang expressed skepticism of state solutions that fail to factor in the highly localized nature of the problem. In Oregon, for example, one reason chronic absenteeism levels haven’t dropped is because “there are whole communities still feeling the effects of wildfires,” said Marc Siegel, spokesman for the state education department. In general, Malkus said it’s unlikely state legislation would be “a rapid-enough response.” And Chang worried that legislators could be “too prescriptive.”

“I think folks have to have local flexibility to unpack the issues,” she said.

But she does think states are helping in at least one critical area: producing more accurate and timely data.

In the past, it was often June before states released chronic absenteeism data from the year before — a fact that delayed efforts to help students. In Rhode Island, the public can even monitor the percentage of students at each school on track to be chronically absent by the end of the year. Malkus would like to see more leaders take that approach.

“If we want to address it with eyes wide open,” he wrote, “chronic absenteeism needs to be studied in real time.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter