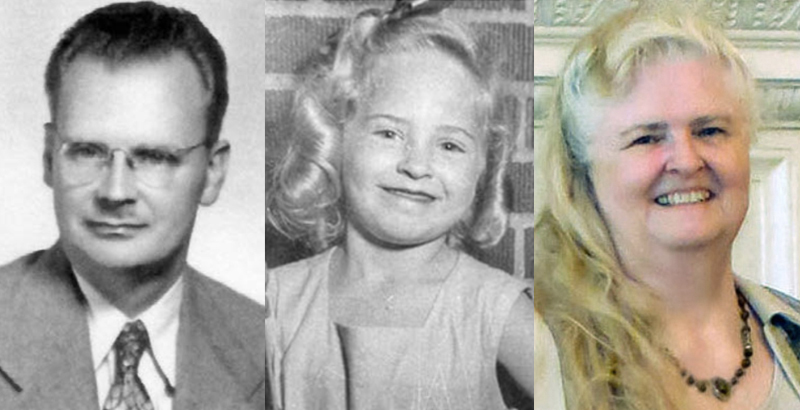

Brown v. Board at 65: Virginia Tryon Smilack Remembers Her Father Fighting for Integration on the School Board — and Her 1952 Kindergarten Teacher Treating Her Differently as a Result

This testimonial is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

Early in January 1988, I drove to Claymont, Delaware, to visit my parents, Evelyn and Sager Tryon, who were still living in my childhood home. I found my parents in the living room, surrounded by papers everywhere! The floor, chairs, couch and organ bench were covered. I had to move some of them before I could sit on the ottoman.

“What’s going on?” I asked. Sitting in his rocking chair, pipe in hand, Dad said, with a sense of urgency, “The Claymont story must be told.”

Over the years, Dad had never really talked in detail about the events of 1950-1954; nor had he told us how he, a white man, had become so emotionally invested in racial equality. Now he fervently expressed his desire to finally tell the story of the community of Claymont, Delaware, and its stand for school integration. As I sat and listened to Dad reminisce, sharing his memories of being actively involved on the school board and in the decisions they made, my mind awakened to my own recollections of those years. Although I was very young when the events that led to school integration occurred (I was born in 1947), I had retained memories — some clear, some disjointed, from that time. Now my childhood memories began to fall into place: the phone calls, going with Dad when he talked to people, the meetings in the house, the tears, the anger, the hope and the joy.

My job as the youngest child was to call Dad to dinner each night. One evening, I went into the living room, where he was sitting in his rocking chair. He was reading the newspaper and not sleeping as he sometimes did. I was startled when he spoke out loud: “Now we can do it!”

He stood up before I could even get his attention. He passed by me, probably not even seeing me, and headed toward the dining room. Where was he going? It did not seem to me that he was going to dinner. However, when he saw that the food was on the table, he stopped and sat down.

It was obvious by his movements and the energy in his voice that he was excited. He told Mom he needed to make a phone call. Within a few minutes, he could wait no longer and went to make that call. I do not actually remember what was said.

Years later he related that he had called Superintendent Harvey Stahl. After he told him about the Delaware Chancery Court’s decision to admit a few black students to the all-white University of Delaware, Mr. Stahl agreed that now, August 1950, was the right time to integrate Claymont High School. With this positive development, Dad said, they could see a way forward.

After approval from black parents was sought and received, the quest for school integration began; the parents began the process by suing for the admittance of their children into the all-white Claymont High School.

I remember several meetings at my home. At one meeting, I recall being asked to hang a lady’s coat on the newel post. The coat had fur on the collar. The lady was much shorter than the men, and she had graying hair and wore a beautiful dark blue dress, like a Sunday church dress. I remember her because she spoke to me. I now know that the lady who came to the meeting was Mrs. Pauline Dyson, a leader of Claymont’s black community. I am not sure who the men were, other than Mr. Stahl. Lawyers, maybe? Board members? I only remember Mrs. Dyson being there at the one meeting, but my sisters say she came to our home several times.

There were times when Dad would take me on errands with him, and I was always happy to be allowed to go along. Being the youngest child, I felt special to go alone with Dad on an errand. One trip stands out because it didn’t make sense to me. We had gone to Fletcher’s Dry Cleaning Store, and Dad and the owner (Mr. A. Eugene Fletcher, president of the school board) waited until another customer had left before talking. Why were we in the cleaners when we took nothing to be cleaned and we brought nothing home? I do not know specifically what they talked about, but it was during this time, so I know they were planning something about integrating the schools.

Another afternoon, Dad took me with him when he walked across the street to visit our neighbor, Mr. George Brown. He had told Mom he was going to try to persuade Mr. Brown to replace a man going off the board. All the board members were white, and Dad needed someone on the board to support the integration plans. He talked with Mr. Brown while I stood nearby listening. I noticed that Mr. Brown seemed uncomfortable. Then I went to watch the older boys playing ball on the side lawn. Finally, when we headed home, I noticed Dad was contentedly smoking his pipe and that he was happy. Mr. Brown had finally agreed to run in the next school board election, which he would go on to win.

After the Delaware courts had found for immediate integration, Claymont was ready to admit all high-school-age black students into the school. However, tensions had mounted because the state court had affirmed the decision to integrate Claymont but no official mandate had come from the state board.

On Sept. 3, 1952, the day before school was to start, Dad stayed home from work. Certainly, it was unusual for him to be home on a weekday. I watched him as he paced back and forth, from his rocking chair to the phone. Mom paced in the kitchen. Both were anxious. Several times during the day, Dad was on the phone, talking with Claymont administrators and board members and with the state school board office.

Legally, the students could not be enrolled without a mandate. However, the school made the decision to enroll the students anyway — without a mandate, and the parents were informed. But, finally, late that night, a representative from the state board called and gave verbal authorization, a verbal mandate, to admit the students. The students could attend school legally.

The next morning, Dad left for work later than usual, because he was still home when my sisters and I were getting ready for school, leaving just before we did. Mom drove me to the Stone School for my first day of kindergarten. Dad had gone to the high school with all the other school board members to greet the black students and to be there in case there was a problem. The students exited the buses, walked into the school and were taken to their homerooms.

Sept. 4, 1952, passed like any other school day. There were no problems on opening day. Although the next day the state demanded that the children be sent home, Claymont stood firm and the students remained. The school year had started.

My first experience in school

For me, kindergarten began that same day that the integration of the high school occurred. I was excited to go to school. Yet the year did not turn out to be a good one for me. My kindergarten teacher obviously did not like me. I entered kindergarten reading a little and came out unable to read. I spent too many hours sitting in the dark, damp, moldy coat room being punished without understanding what I had done wrong. It was not until many years later that I wondered if she had been angry at Dad for his support of integrating the schools and simply took it out on me. I wish I had known then that this could have been another reason and that I was not simply a bad, stupid kid. I still do not know.

Virginia Tryon Smilack is the daughter of Sager Tryon, a member of the nearly all-white Claymont, Delaware, school board that led an underground movement to desegregate Claymont schools two years before the Supreme Court handed down its landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

This testimonial is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The 74 and funded The Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research to produce the new book Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter