Brown v. Board at 65: Joan E. Anderson, Daughter of Key Plaintiff, Pays Tribute to the Delaware Superintendent Who Defied State Orders to Desegregate Classrooms

This testimonial is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

It was August now, and all Delaware cases had been won. With the verdict was the mandate that the schools had to integrate immediately. Claymont was the only school that decided to accept all students eligible to attend grades 7 through 12, including those who were not part of the Belton case. It meant that I and my two sisters, Merle and Carol, would be attending Claymont High. There was much relief for me.

The strange thing about all of this for me was to have moved from an almost segregated environment (Wilmington) to an all-white environment (Ardencroft) and then to an all-white school. But I was happy with all the decisions my parents made. And I knew I would continue to get a good education and make new friends.

It seemed all was going well in preparation for the opening school day. The final verdict had been rendered Aug. 28, 1952. However, we needed a written mandate to attend, and it was not being sent by the attorney general’s office. It was now Sept. 3, 1952, and I was getting a little anxious, due to the fact that school was scheduled to begin the next day. And I wondered if I might still have to attend Howard High. But the Claymont school superintendent, Mr. Harvey Stahl, decided to enroll us anyway. I still remember being in his office on the third and receiving his warm welcome. But he also told us that he wasn’t having any problems at his school. I was a little concerned at the time that there might be problems.

That night I had anxious moments, because we still didn’t know where we would be attending school, even though we were enrolled at Claymont. Later that evening, we received a call that we had been granted a verbal mandate to attend Claymont. I immediately felt peace that it was resolved.

On Sept. 4, 1952, we attended Claymont and received a warm welcome from all, including my new teacher. There were no police or reporters. It had been decided to keep it as quiet as possible. Whatever nerves I had were quickly relieved. Everyone was friendly. I remember my mother telling me that many of the staff and teachers hugged her and told her how happy they were that her children were attending Claymont High.

On Sept. 5, 1952, Mr. Stahl received a call from the attorney general’s office, telling him to send us home because we didn’t have a written mandate to attend. Fortunately, he refused, and the teachers signed a petition that they wanted us to stay.

Later that day, Mr. Young’s office called back to say we could stay, but that no other schools could integrate. I found out about it when I arrived home from school that day, and was glad I could stay. I was already getting adjusted to the school routines.

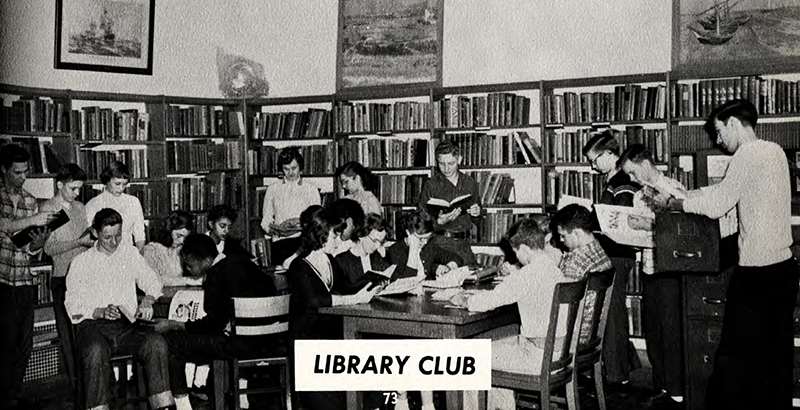

Joan E. Anderson’s brother Victor, in the plaid shirt, with the Art Club at Claymont High. He started attending Claymont High with Anderson after helping to integrate Arden Elementary. (Photo courtesy of Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision)

The school schedule was OK, and I made some friends. I was immersed in the classes and homework. A couple of weeks into the school year, my two sisters and I had a situation which we didn’t know how to resolve. Being in an all-white school, we realized that our aunt (sounding like aaunt) was no longer an aunt, but actually an ant (spelled “aunt”). We didn’t know what to do about it. Finally, we decided that at home she was aunt and at school she was ant (spelled “aunt”). I still use this interchangeably to this day.

There were activities I was interested in. I joined the Glee Club. I had convinced myself that I had a good singing voice. However, I had difficulty staying on key. I was put in the alto section and was told to sit close to the person next to me and try to follow along. There were times I just had to open my mouth and let nothing come out. But I tried.

I found that it wasn’t difficult getting adjusted to being in an all-white school. I had been living in an all-white community for a few months. There was an adjustment in the new environment and new routines. But I was happy to be in Claymont High.

Joan E. Anderson (back left) with her parents Leon and Beulah Anderson, and her sister Linda (seated on the floor), who worked hard for the integration process in Arden, Claymont, and Wilmington, Delaware. (Photo courtesy of Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision)

In addition to trying to sing in the Glee Club, I also signed up for softball and basketball, as I enjoyed sports. Basketball was a little difficult, because in those days, girls weren’t allowed to run up and down the court. We had half-court basketball. I usually had to play guard and that meant staying under the opponent’s basket. I rarely had a chance to shoot the ball, probably because the ball wouldn’t go in the basket for me. But before I graduated, a picture was taken of me trying to do a layup for the yearbook. Fortunately, it doesn’t show that I missed. Of course, women’s basketball is totally different today.

Softball was different, and I excelled at it. I was the pitcher for the team. My first game, I was so nervous, I pitched the first ball over the fence. I cleared everything, including the batter, catcher and umpire. I settled down and we won — I think. Maybe I just thought we won.

One incident that happened was a white softball team refusing to play us. We were very disappointed, but we consoled ourselves with each other and the staff. We decided to move on, forget it and start preparing for the next game. They did forfeit the game, but we would have liked to have earned the win. It was a reminder to me of the segregation around me. My classmates were great, though, always supportive of me. Again, I have to say that I was happy at Claymont.

Carol Anderson Neff is the daughter of Leon V. Anderson, a plaintiff in Delaware’s Belton v. Gebhart case that was later consolidated as part of the Brown v. Board Supreme Court case.

This testimonial is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The 74 and funded The Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research to produce the new book Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter