Gregory: 4 Ways Teachers in Segregated Classrooms Can Desegregate Their Students’ Learning

Updated May 20

This essay is part of a special series commemorating the 65th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation case. Read more essays, view testimonials from the families who changed America’s schools and download the new book Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision at our new site: The74Million.org/Brown65.

Schools are not immune from the inequities and societal issues that plague our society at large. Brown v. Board of Education was a poignant example of that when it was first argued in 1952, while segregation was rampant in society, not just in schools. Today is no different.

“Public trust in the government is near its historic low. And in 2017, Americans were far more politically polarized on topics like immigration and health care than in the early 2000s,” according to Gallup. Journalists are now routinely assailed by politicians. The bruising confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court led The Washington Post to speculate that “even ‘our least damaged institution’ might now be viewed with increasing levels of skepticism.”

As was the case in 1954, our schools reflect, challenge or advance the inequities and issues at play across our nation. Brown v. Board of Education embraced this reality and actively moved to change it. It overturned years of discriminatory practice in education supported by legal decisions and was a key element of the larger civil rights movement. In order to reach the final decision in the case, the Supreme Court had to reconsider long-held truths about education in the nation. In the syllabus created after the Brown v. Board decision, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren wrote:

“The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation.”

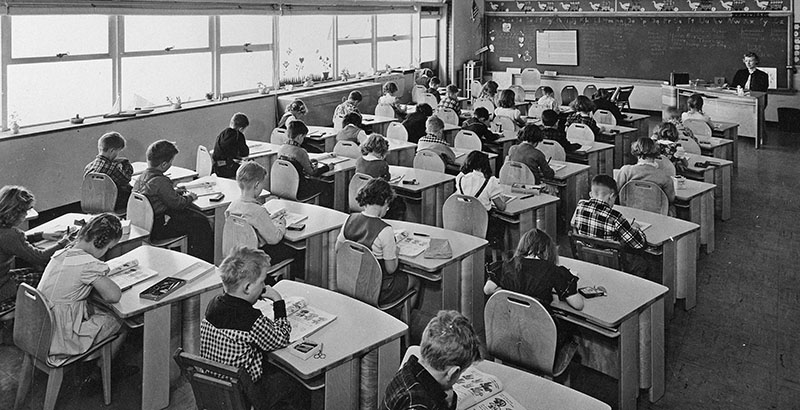

It is worthwhile, 65 years later, to revisit this language for the sake of our students and future generations. What, actually, is education’s present place in American life throughout the nation? In 2018, many schools are still segregated (though not legally) and there are many indicators that despite the reality of desegregation, many schools are not in fact truly “equal.” How must we build on the foundation set by Brown v. Board?

Context matters

Many argue that it is difficult to create desegregated schools in segregated communities, given that residential segregation is actually the result of racially motivated law, public policy and government-sponsored discrimination. However, culturally relevant teaching practices, teacher coaching and strategic use of technology could help us overcome the barriers that our neighborhoods present to desegregation. Whereas helping students explore and interrogate disparate perspectives on the reasons behind the Emancipation Proclamation may have been a part of the curriculum in woke educators’ classrooms for some time, that approach to teaching — contesting long-held historical narratives — has certainly not been present in every classroom across the nation. Now it is possible for educators to connect their classes and lessons to schools across the city, country or world to make those discussions occur in real time, with real people. This can be accomplished with an older version of a smartphone, and so it is definitely within the reach of every educator in the nation.

For example, as students are learning about the arrival of Europeans to the Americas in the 1400s, educators could support them in comparing and contrasting how those events are taught in the U.S., in Canada and across the Caribbean. Unpacking this history could involve connecting with students across North America over a learning platform like Skype in the Classroom or Digital Promise Story Map to learn about how the arrival is taught similarly and differently. This could lead to generational research as students interview family members about their memories of how this important history was taught and support a deeper shared analysis and debate of the different ways in which important cultural events are reflected, depending on authorship.

Here, teachers in racially segregated classrooms can guide their students to explore the reasons different perspectives exist on a topic and learn how to engage with others who hold different perspectives. They also learn to have disagreements that are not disagreeable, a worthy skill to develop. Overcoming the physical barriers that segregate students supports them to develop real relationships, to understand and practice the civic discourse that has become so hard to find recently.

Connecting teaching to life

What are we preparing our students for? If our lessons help us prepare students for life and not just the next assessment, our teaching helps to close the gap that segregation creates. Conversations become less about what is in the textbook and more about what is in the world. The most skilled teachers follow Paulo Freire’s advice to “teach the word and the world,” driving students to learn a literacy that works for books, people and community-building. Here is an example: Ask third-grade students to share with one another why they need to understand what the text says explicitly and make logical inferences from it. Where and why might they need to do that in real life? The goal is for students to understand that what is meant may not be what is said and what is said may not be what is meant. What might happen if they don’t know how to do that?

When we center our teaching on questions beyond the textbook, we start to create the type of pedagogy that is relevant to students, driving their deeper engagement. What students are learning starts to feel as if it is meaningful beyond the four walls of a classroom. Learning then becomes the foundation of a life that can be carefully examined and well lived.

Self-exploration is possible and impactful

In our segregated spaces, we sometimes limit ourselves to the hokey activities that have been around for decades, like “International Day,” when we eat foods and wear clothing to represent a country. Or we have the single student of a different race answer a question on behalf of the entire racial group, in a move that has disempowered learners repeatedly. Instead, we could turn our segregated spaces into mini-action research labs, where we purposely explore the diversity within our perceived sameness.

In such a space, a high school government class might hold the same in-school election of local or national candidates, as has been done for years. Leading up to the election, however, students could research candidates’ positions and the positions of their party and engage in debates serving on a side that is not naturally their own. This setting would force a deep exploration of the details behind a 30-second TV advertisement and build a case for diversity of thought where there initially may have appeared to be none.

Coach teachers to success

Teachers need support to have the kinds of conversations that lay bare their own mindsets, especially those that might get in the way of delivering on the promise of Brown v. Board. Schools that establish a culture of coaching are more likely to ensure that teachers get that support. A culture of coaching in a school establishes a few things as norms: giving and receiving feedback, stretching (and supporting) thinking, and engaging in the kinds of conversations that drive improvements in teacher practice.

When there is a culture of coaching in my school, I am more likely to feel comfortable reaching out for support with specific students and am more likely to investigate with my coach how my perception of those students (because of their performance, their race or ethnicity, etc.) might be deepening their learning gaps. With coaching, I can unpack my mindsets and be better able to teach in my segregated space as if it were desegregated because I don’t see all of my students through the same lens.

We all have mindsets; they are how we think about our talents and abilities. In schools where a culture of coaching exists, the transparent conversations necessary to discuss those mindsets in safe spaces can occur. In 1954, the plaintiffs contended that segregated public schools were not “equal” and could not be made “equal.” Perhaps. But they can be made wholly responsive to the needs of students and their teachers. Coaching makes that possible because it normalizes the kinds of conversations that shift negative mindsets, as both the coach and teacher push one another to continually improve.

Brown v. Board laid the foundation for creating the types of schools that would drive our nation in the direction of success. And our work now requires even more from us than that case did. When U.S. Supreme Court Justice Warren handed down the unanimous decision of the court, this is what he said — in 1954:

“Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments … In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.“

These words remain true today, 65 years later. Let us continue to make the right available to all on equal terms, desegregating our spaces for all of our students, regardless of whom they sit next to in the classroom.

A version of this essay first appeared on CT3’s website.

Nataki Gregory was founding principal of the Maya Angelou Public Charter School, Evans campus in Washington, D.C., a college prep alternative school for students who had experienced trauma and failure. She is vice president of education and strategic partnerships at CT3, which provided professional development, coaching and teacher training in underserved schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter