The Price of Being First: Effort to Rename Brown v. Board Reveals Family’s Pain

A failed quest to rename the famed school desegregation case for the South Carolina family who filed first is about more than legal recognition.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

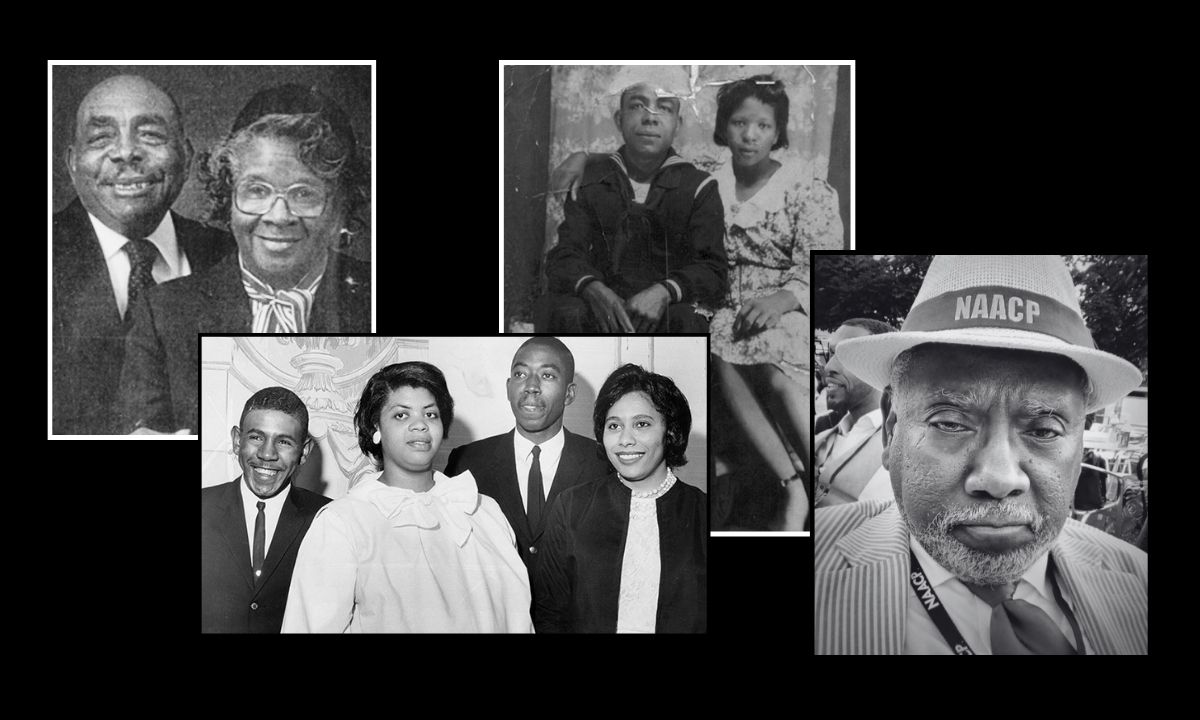

By the time Cecil Williams turned 14, he was already photographing the civil rights movement in South Carolina.

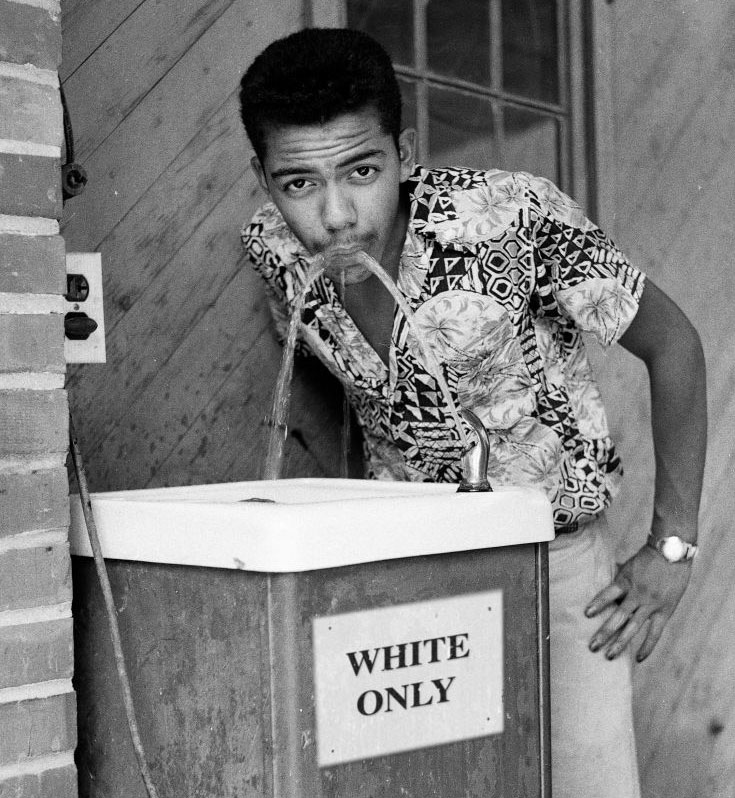

As a teenager in the 1950s he followed and documented Briggs v. Elliott, the South Carolina case that challenged segregation in public education. Briggs was eventually appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court where it became one of five cases consolidated into what is now known as Brown v. Board of Education.

Williams, now 86, still reflects on the injustices he witnessed in South Carolina in the wake of the case: most petitioners lost their jobs and some were driven out of town. The consequences have reverberated for generations.

“They were ostracized in their own community,” he told The 74.

Since the 1960s, Williams has asserted that the 20 parents of Briggs v. Elliott faced a second injustice: They were forgotten. Despite being the first of the five cases to make it to the Supreme Court, Briggs was not chosen as the lead case and was therefore relegated to the position of “et al.” in the seminal Brown v. Board’s name. This naming meant that despite the families’ sacrifices, their stories were removed from the foreground, according to Williams. For decades, he has been advocating for a correction, asking over 100 attorneys to take on a case that would challenge the ordering — and the naming — of Brown.

In some ways, Williams is a hidden figure among hidden figures, who took up the cause of renaming Brown even before Nathaniel Briggs, the 76-year-old son of the lead plaintiff in Briggs v. Elliott, Harry Briggs, came on board and before South Carolina attorney and civil rights organizer Tom Mullikin agreed to argue it pro bono.

Mullikin would spend years interviewing the families from the original Briggs case before filing his brief before the U.S. Supreme Court in November 2023. Earlier this month, the justices denied the petition without comment.

“I would do it again,” Mullikin told The 74. “I would spend another four years doing it. And I’ll spend the rest of my life talking about it because it’s an injustice. Sometimes, there’s a price to being first. And in this case, there’s no denying that people lost their lives, their economic fortunes, and their livelihoods because of their courage and stepping out.”

While on its face a legal battle, the quest to rename the landmark Brown case lays bare how steep that price was and how lasting its painful legacy. For Nathaniel Briggs, it was the dissolution of his family. His father was fired from his job as a gas station attendant; his mother from hers as a motel maid.

His father began working at a family member’s farm but when he took his cotton to market, Briggs said, people refused to buy it because of the association with his last name. In 1957, out of options, his father moved to Miami. At the time, Briggs was 9 years old. He was devastated when his father was forced to leave the family behind.

“Once a month he would call. I’d hear my dad’s voice for a couple of minutes … I’d put those coins in the old, black dial-up telephone thing, and I’d hear my dad’s voice.”

South Carolina — and the stories of the Briggses and the other families in Clarendon County — have remained largely invisible, despite the notoriety of the titular Brown case, according to Nathaniel Briggs.

“The original signees of this petition, the seniors, they’re all dead,” he said. “So I’m saying, who can speak for dry bones? Me. I’ll speak for those dry bones that cannot speak for themselves … Don’t let this nation, a historian, or a writer write you out of the picture.”

A clerical error or a strategic move?

The Supreme Court brief that Mullikin filed on behalf of Nathaniel Briggs, as well as Beatrice Brown Rivers and Ethel Brown Marshall, two of the signatories of the original South Carolina petition, asserted that Brown had been incorrectly named due to a clerical error.

Thurgood Marshall, the civil rights attorney and first Black Supreme Court justice, filed Briggs v. Elliott in the fall of 1950. Initially, Black parents in Clarendon County were just requesting school buses for their children. But by the time the case was ultimately filed against R.W. Elliott, the school board president, the parents were challenging segregation in its entirety.

Eventually, Briggs was appealed through the court system and was the first of the five consolidated cases to reach the Supreme Court. It was returned back to the lower district court in 1952. According to Mullikin’s brief, when the case again made its way to the Supreme Court for the second time “the Clerk inadvertently docketed the Briggs case after Brown instead of placing it back as the first case filed. This inadvertent clerical misstep deprived the petitioners their rightful place in history in spite of the great physical, emotional, and financial risks taken by each petitioner. The petitioners request that their place in history be restored by the simple act of reordering the petitioners to the just and accurate place.”

Mullikin noted that there may be people who view this case as an attempt to pit the involved families against each other, but that to his knowledge “there’s none of that happening.”

“This is in no way to marginalize what [the Brown family] went through or the importance of their case. It’s simply a matter of factual accounting of which case is first. In no way was our collective efforts meant to marginalize or minimize the sacrifice that those families made.”

“We’re not in any conflict with what the Brown case stands for, but we are in conflict with the naming of it,” Williams, the civil rights photographer, said.

Cheryl Brown Henderson, the daughter of the lead plaintiff in the Brown lawsuit, declined to comment on the record. In an interview with Education Week she said that while she did not oppose the South Carolina effort, she had expressed her misgivings to the South Carolina descendants. She told the outlet that the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research had worked to promote the history and legacies of all five cases that made up the Brown and Bolling decisions.

Read more here — BROWN V. BOARD: The Untold Stories

Some historians believe that Brown was given preference for strategic reasons: that the lead case would have an easier path coming out of a “border state” like Kansas vs. a Deep South state like South Carolina and in Brown, the court potentially saw a chance to push the school segregation issue out of the Jim Crow South and onto a national platform.

Going home to Clarendon County

After the original court filing, the Briggs family splintered; with Nathaniel, his mother, sister and brother attempting to reunite with his father in Florida, leaving their grandmother behind, and other brothers moving north to New York City.

A year later, the Florida family members returned to South Carolina. Briggs enrolled in Scott’s Branch High School, the subject of Briggs v. Elliot and which remained segregated despite the high court’s ruling almost a decade before. Even at the all-Black high school, Briggs said he faced discrimination because of his last name. “Not all of the teachers liked the Briggs children because you’re upsetting a system,” he said.

Those hardships prompted another move by the rest of the family to New York City in the early 1960s. Today, Briggs lives in New Jersey but has returned to South Carolina every year for the past six decades.

“I love my community,” he said.

In 2014, almost 100% of the schools in Clarendon County were de facto segregated.

“Most of the white students attend private schools while black students attend public schools, which are still notoriously underfunded,” Mullikin wrote in his brief. Scott’s Branch Middle/High School has a 95.7% minority enrollment and 100% of the students are economically disadvantaged, according to the brief, despite the county of 31,000 being almost evenly split demographically.

In some ways, these numbers are unsurprising since school segregation is still a core feature of American public education, said Ansley Erickson, associate professor of history and education policy and co-director of the Center on History and Education at Columbia University’s Teachers College. In 2021, approximately 60% of Black and Hispanic public school students attended schools where 75% or more of students were students of color.

It is important to recognize the burden desegregation efforts put on Black families, she added.

“The key thing that [the Briggs] case can bring to our attention is how much work desegregation required of Black students and families,” she said. “The Supreme Court decision in Brown was not self-executing, meaning that it didn’t automatically tell districts what to do. It established the legal standard, and then made it possible for districts to be sued by local families and attorneys. And that means that it shifted the labor onto families like the Briggses, families like the Browns, families like hundreds that we could name if we look at every local school district that was segregated, and where someone brought the case to court. And that labor is tremendous.”

“Every one of these local districts should recognize the people who did this labor on behalf of justice.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter