Leaving Los Angeles: These 10 LAUSD Schools Lost the Most Students During COVID

Students from both low-income and affluent areas are moving beyond and within the district

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Enrollment in Los Angeles Unified schools has been dipping for years, declining even more during the pandemic — but which schools saw the biggest drops and why?

The enrollment drop of close to 6% during the pandemic came from a concoction of factors including families moving out of state, students switching to non-LAUSD schools with looser COVID restrictions, and children having to stay home to care for family members.

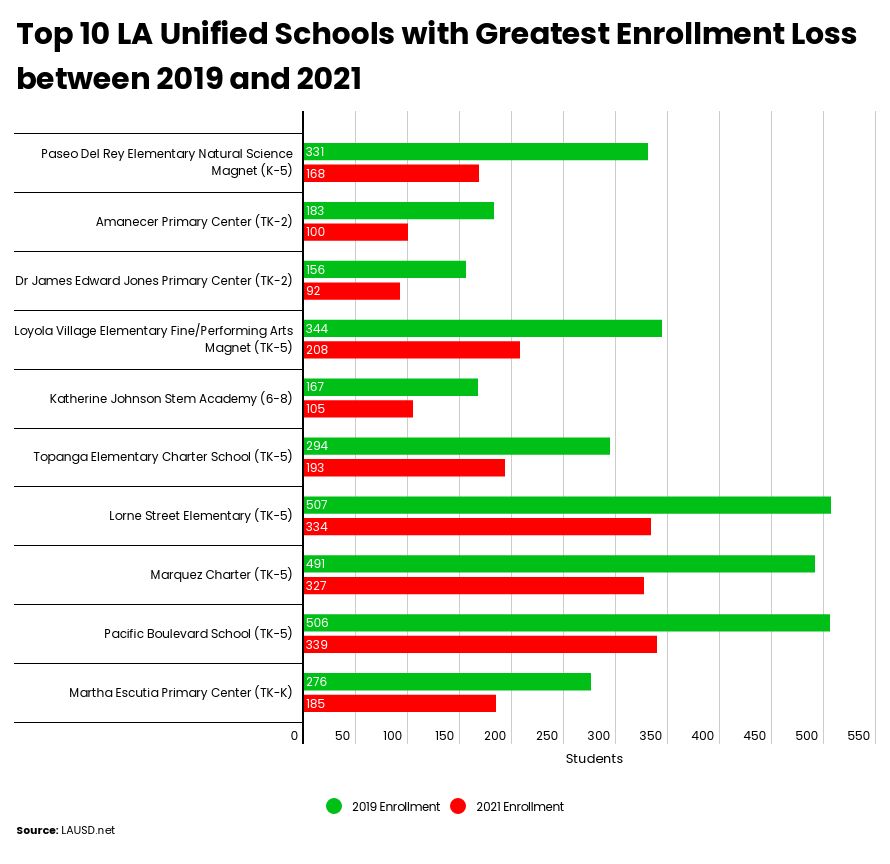

An analysis of LAUSD data by LA School Report showed of the top ten district schools that lost the most enrollment from 2019 to 2021, eight served largely non-white students, while two enrolled mostly white, affluent students.

While some students left LAUSD entirely, others changed schools within LA Unified. As a result, some LAUSD schools with specialized programs, such as language immersion, saw enrollment increase during the pandemic.

The overall decline prompted LA Unified superintendent Alberto Carvalho to raise the issue of whether the district will have to shut schools.

“We will cross that bridge if we need to,” Carvalho said in August. “And if we need to, this will be done in a very careful, cautious way with full engagement of the communities. We’re not there yet.”

An LAUSD spokesperson said in a statement that enrollment had “improved” at many of the ten schools, but declined to provide numbers. In a statement she said the district was focused on “several new strategies to bring kids back into our school system, such as universal transitional kindergarten and increased transportation availability for residential students.”

Here’s what LA School Report’s analysis found on the ten schools with the biggest percentage declines:

Which schools lost the most students?

Five of the ten schools with the biggest enrollment drops are in the West region of LAUSD and are part of Board District 4, a district that includes many middle and upper middle class students.

This includes Topanga Elementary Charter, with a predominantly white student population, in the Santa Monica Mountains that lost over 100 students; and Marquez Charter, also a majority white school in the Pacific Palisades that lost 164 students. Both schools belong to the 51 LAUSD-affiliated charter schools and are in areas with median household incomes above $130,000.

District 4 school board member Nick Melvoin said students in his district have proximity to many options — both public and private. In recent years, and more so during the pandemic, families have left LA Unified schools.

“Within my district, you have Santa Monica Unified, Culver City Unified, Beverly Hills Unified,” he said. “You also have some strong independent charter schools and some private schools. On the west side of the West Valley, where there’s more affluence, families can afford those other options. It’s a competitive landscape.”

Niloofar Shepherd, the parent of a fourth grade student at Marquez Charter, said many parents left Marquez because of COVID restrictions.

“A lot of people weren’t willing to ride it out,” Shepherd said. “Our experience was that the teachers did the best they could and we didn’t feel at all that our kids were getting short shrift … but the way I’ve heard it is that a lot of people pivoted to private school.”

More than one in four California parents switched their child’s school during the pandemic, with most favoring charter schools, according to a recent poll conducted by the Policy Analysis for California (PACE) and the USC Rossier School of Education. The poll found an 8 percentage point increase in charter school attendance among those who switched schools.

“Whiter and more affluent folks were especially likely to change their kids’ schools during the pandemic,” said Morgan Polikoff, associate professor of education at USC and co-author of the poll. “If you’ve moved to a neighborhood because of the ‘good public schools,’ but you’re not satisfied with how public schools are handling COVID — and you can afford to — then you would be more likely to move your kid to a private school.”

But Melvoin said not all of District 4 fits this demographic. Lower income, nonwhite families also left the district, unable to afford to stay.

“There are some schools in even District 4 that are high poverty and those are families that are getting pushed out of LA because they can’t afford to live here,” Melvoin said. “There are a lot of kids who are bused into some of those schools and so if they started going to school in their neighborhood, or they had to move even further away from the west side… because of economic factors” they stopped attending District 4 schools.

Paseo Del Rey Elementary Natural Science Magnet in District 4, for instance, which overwhelmingly enrolls Black and Latino students and is 66% low income, lost nearly half of its students from 2019 to 2021, making it the school with the biggest decline.

LAUSD District 2 school board member Monica Garcia, who represents the center core and East side, also said the families in her district, mostly low income and nonwhite, have been pushed out by job loss, income inequality and unaffordable housing. District 2 includes neighborhoods such as Boyle Heights, Downtown L.A. and East L.A.

But being pushed out of their homes isn’t the only reason families are leaving some LA Unified schools.

Amanecer Primary Center in East L.A., a school with a 98% Latino student population, had the second largest decline of the 10 schools, dropping from 183 students in 2019 to 100 in 2021 — a 45% decrease.

García said that for Amanecer, a school that goes up to second grade, the decline is attributed to spots opening up at Rowan Avenue Elementary just down the block, a larger K-5 school that can accommodate bigger families.

“What happens if we consolidate schools? I don’t want to say close, but repurpose a primary center to have all the kids go to the elementary school when they’re very close to each other?” she said. “So now there’s an option for families at some of our elementary schools that grandma or the caretaker or mom or dad, they don’t have to take the kids to two sites, they can take the kids to one site.”

Where schools are seeing growth

Schools that saw increased enrollment offered families educational opportunities most others don’t have.

Augustus F. Hawkins Critical Design and Gaming STEM Magnet saw a 120% increase in students, jumping from 481 students in 2019 to 1,058 in 2021. Samuel Gompers University Pathways Medical Magnet saw a 76% bump in enrollment, and Charles Drew University Pathways Public Service Academy saw a 48% rise.

In District 4, enrollment increased by 8% at Cowan Avenue Elementary — a school that offers Spanish immersion and holds a gifted international humanities magnet center. Cowan Avenue Elementary has a predominantly Black student population.

“I’m a big believer that if you build exciting programs, people will come back to their local public schools,” Melvoin said. “When we have really great exciting programs like dual immersion programs, we actually get kids from those other districts — so people coming in from Culver City and coming in from Santa Monica.”

Polikoff said that adjusting to what parents want will stem some of the enrollment losses.

“It has to start with getting to the root of what’s causing it and seeing which of those factors are malleable,” he said. “And probably a lot of it just has to do with improving the quality or the perception of the education that’s being offered.”

Melvoin said the district will inevitably need to face the reality of the landscape, that the general decline will not magically bounce back up to the levels seen 20 years ago, when LAUSD had 750,000 kids enrolled.

“You have to adapt and look at other uses for school property,” he said. “I’ve been a big proponent of trying to build housing on school property. If the school had 2,000 kids and now it has 1,000, rather than trying to get another 1,000 kids who don’t exist anymore, let’s look at building some housing for families or for educators.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter