In Los Angeles and New York, Fights Escalate Over Sharing Schools with Charters

One parent said debates over co-location have “simmered over into the community.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Actions in the nation’s two largest school districts are testing the idea that charter and traditional schools can exist under one roof.

In Los Angeles, the school board is expected to vote this fall on a measure that could significantly limit the practice, known as co-location.

And in New York, the United Federation of Teachers plans to appeal a judge’s Aug. 11 decision that allowed Success Academy, a large and high-performing charter network, to open new schools in two district facilities.

“In both New York City and L.A., the general relationship between traditional public and charter schools is not great, so asking schools from these two different sectors to share a building could be contentious,” Sarah Cordes, an associate professor at Temple University who has studied co-location, told The 74. “If schools view each other as competitors rather than collaborators, it will make co-location challenging.”

Charter schools have long faced challenges securing facilities and financing renovations. California voters passed a law in 2000 that requires districts to provide facilities for charters, including through co-location. Research shows the policy can work if district and charter leaders are willing to compromise, and can even benefit district students. But such partnerships are hard to come by in cities with strong teachers unions, where disputes over issues like parking and access to the gym can spark resentment between charter and district families.

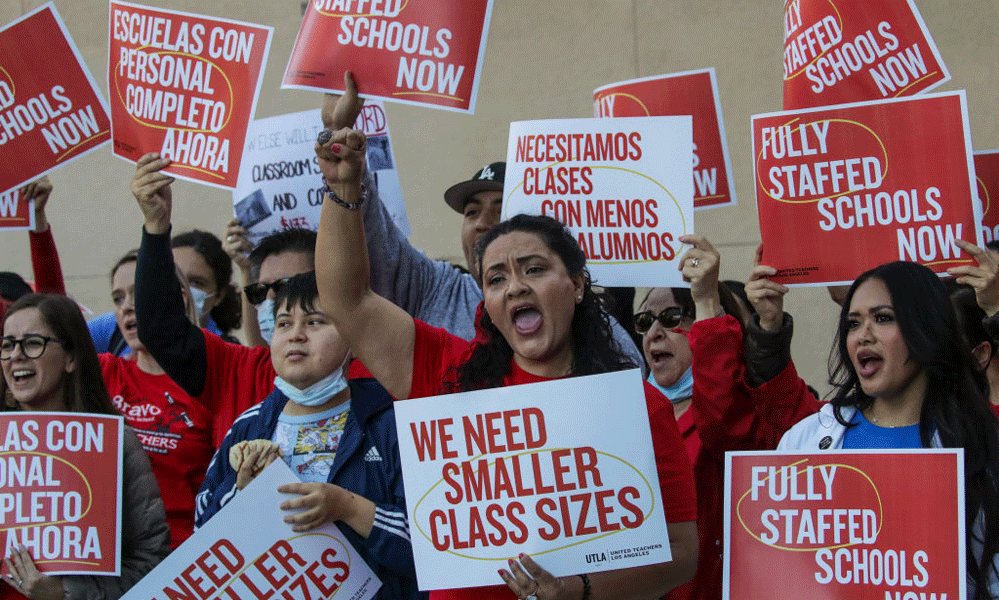

Co-location bubbled up as a major issue in United Teachers Los Angeles’s strike against the district in 2019. Following the strike, board President Jackie Goldberg and fellow Board Member Nick Melvoin pushed through a $5.5 million pilot program on facility upgrades that could make co-location more tolerable, such as designated entrances for charter students and staff and separate drop-off and pick-up areas. But that wasn’t enough to overcome the union’s argument that charters take space away from district students.

For Board Member Rocio Rivas, who wrote the proposed resolution with Goldberg, the current proposal is a step toward fulfilling a promise to her supporters during last year’s campaign. In an interview for Jacobin, a left-wing website, she called co-location ”a cancer that comes in and then metastasizes and spreads.

A draft of the resolution says the practice “has a tangible negative impact” and would require Superintendent Alberto Carvalho to write a new policy that would prohibit co-locations at the district’s 55 community schools, which offer food pantries, health clinics and other services for families. The resolution, which the board is expected to discuss Sept. 19, would further bar co-location at the district’s 100 low-performing “priority” schools and those targeted by the Black Student Achievement Plan.

Those special programs shouldn’t displace charter students who need classrooms for “core educational coursework,” wrote the California Charter School Association. The group would consider suing the district if it moves forward with the policy. The association has taken the district to court over the issue before. The proposal, the group says, would lock charters out of at least 236 schools and impact 28 facilities that are currently co-located.

Charter parents said animosity toward their schools, including protests outside the school gates in recent years, has affected students.

“It’s simmered over into the community,” said Angelica Solis-Montero, who has two children at Gabriella Charter School, which shares a campus with Logan Elementary in the Echo Park neighborhood. “These families shop in the same places; they access the same public resources. One group of students has been pitted against another group of students.”

But charter advocates aren’t the only ones opposed to the proposal as currently written. Twenty-six organizations, including Educators for Excellence Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Urban League, wrote a letter to the board, saying the resolution is filled with “hateful rhetoric.”

“The charter fight is over. [Charters are] under enrolled. They’re not growing,” said Ana Teresa Dahan, managing director of GPSN, one of the nonprofits that signed the letter. “We need to really focus on improving the experience for kids in all our public schools.”

‘In limbo’

Co-location is a more recent policy in New York. A 2014 law permits new charters or those adding grade levels to access space in district buildings. But in allowing Success Academy to move into those two buildings, UFT said New York Supreme Court Judge Lyle Frank didn’t consider a new state law that sets caps on class sizes, putting an even greater premium on available classrooms.

While the dispute focuses on just two schools, it exemplifies the challenges that arise when multiple schools occupy the same building.

Ken Zhang, principal at Success Academy Rockaway Park Middle School, said it’s taken about four years to get a permanent site. Until this year, his students shared a building with another Success Academy elementary and two district schools. Now they’ve moved into P.S. 225 in Queens, site of the district’s Waterside Leadership School.

“We were in limbo at every turn,” he said. Co-location can work, he said, when principals are clear about what’s important to them — for him, it’s access to the stage for his theater students — but are willing to bend in other areas. “I’m not going into these meetings looking to take space away from their kids.”

But Elli Weinert, a district music teacher and one of the plaintiffs in the UFT lawsuit, said just because a building has unused space doesn’t mean it’s suitable for young students. She teaches at Professional Pathways High, one of three small schools serving high school students or adults in the Frank J. Macchiarola Educational Complex in Brooklyn.

Success Academy Sheepshead Bay, a K-4, moved into a space in the Macchiarola complex previously occupied by another high school.

“We do need something in that space,” said Weinert. “But it was built for the young adults in that neighborhood.”

She’s not opposed to co-location in general. Staff and students from the four schools within the Macchiarola complex, she said, learned to accommodate each other “like roommates.”

“At first it wasn’t easy — four different schools with four different visions,” she said. “We’ve been able to work through some difficult stuff.”

Sharing space with a charter can actually boost math and reading performance among students in traditional schools, according to research Cordes published in 2017.

But she agreed that given the practical challenges co-located schools face, it can be hard to “maintain a unique school climate.”

“I’m not sure anyone has created a framework for how to make this kind of arrangement successful,” she said. “There needs to be a lot more work done in this area.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter