Nashville’s ‘Navigator’ Tries to Keep Students in Remote Learning From Getting Lost in the System

This article is one in a series spotlighting the broader consequences of families disenrolling their children, students changing schools and children going missing amid the coronavirus crisis. See all our coverage at ‘COVID’s Missing Students.’ (If you or a student you know changed schools or stopped going to class altogether because of the pandemic, tell us your story. On Twitter: #WhereAreTheKids and #IAmHere)

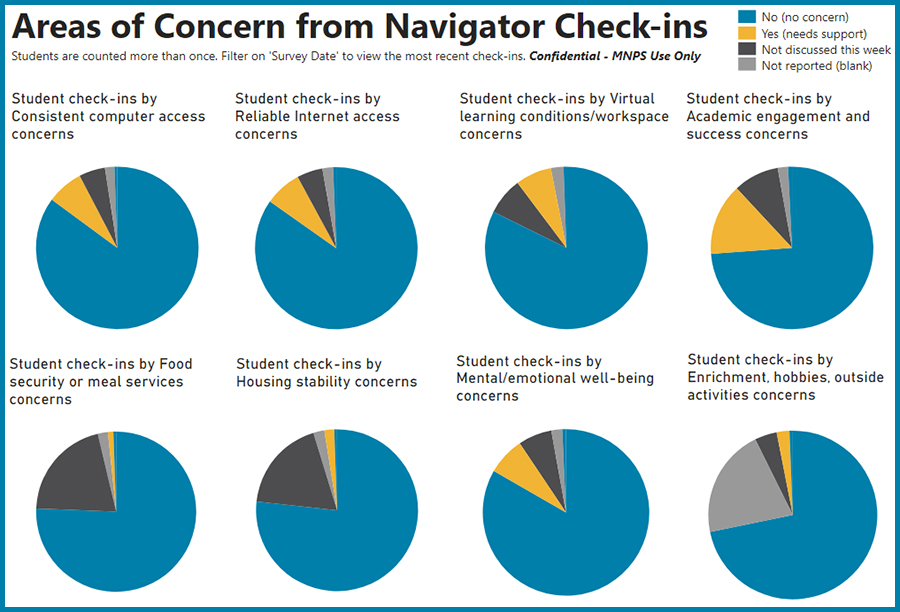

When the school year began, Catherine Knowles thought the Nashville district had about 200 homeless students.

That was before the Navigator program kicked in.

The program, tracked through weekly phone and video calls, is an ambitious effort to keep students and families from slipping out of reach as distance learning extends into next year.

Navigator’s count revealed a deeper problem. Another 1,200 families had unstable housing. Some doubled up in apartments with relatives and others weren’t sure if they’d make next month’s rent.

“It really just sets the stage for [housing] to be an acceptable topic for us to care about,” said Knowles, the district’s homeless liaison. And with a national eviction moratorium set to expire at the end of this month, she added that many of those families could be left without shelter.

New this fall, Navigator is what district administrator Keri Randolph describes as the virtual equivalent of talking to the students in the hallway. The district seized on the pandemic as a chance to stay in touch with every student and devote to any who needed it the kind of attention typically reserved for the most at-risk students. Their contacts might need academic supports like tutoring and enrichment, or help with the basics, like food and health care.

“One of the great casualties of this whole pandemic is relationships,” said Paul Reville, Harvard University education professor and former state schools chief in Massachusetts. “There’s got to be some connective tissue between the families and the school system.”

As districts across the country struggle to find missing students who aren’t participating in distance learning, the Metro Nashville district may serve as a model of how to prevent them from disconnecting in the first place.

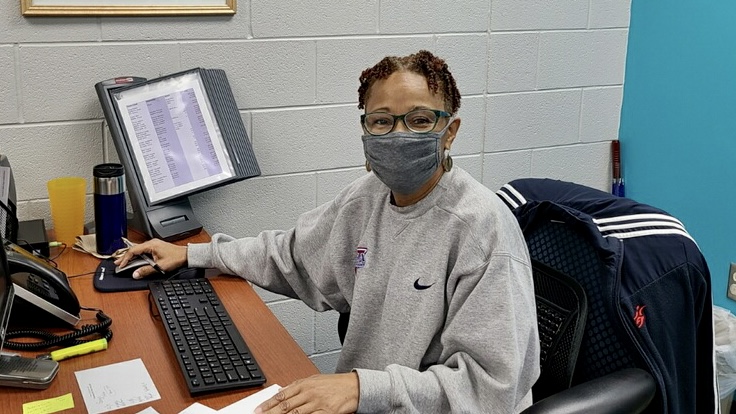

Navigators — a broad cross section of school employees including teachers, lunchroom workers and bookkeepers — have completed roughly 220,000 calls to parents and students since school started in August. In the process, they’ve discovered that students fall through the cracks for reasons both complex and often unexpected.

Eva Gaskin, who teaches English learners at Hunters Lane High School, began contacting a 15-year-old girl in August. Their conversations covered academics and personal goals. But it wasn’t until October that the student opened up that she had been living on her own for months after her father, the only parent in the home, abandoned her for a girlfriend. The rest of the family is in Guatemala.

Gaskin used Navigator to refer the girl to children’s services, and stays in contact with her by text. “I know she needs counseling,” she said. “Who can come out with their mental health intact if their father abandons them for a woman?”

A ‘promising experiment’

The idea began simply. Standing in “a socially distanced room” this summer on her first day as the district’s executive officer for strategic state, federal and philanthropic investments, Randolph listened as school leaders spoke of a disconnect between schools and families. That’s when she suggested Navigator, inspired by her doctoral work at Harvard, where Reville advocates for K-12 students to have personalized plans tailored to their specific needs and interests.

While calling Nashville’s effort a “promising experiment,” Reville said that getting educators to focus on students’ overall wellbeing can be like “trying to turn the Queen Mary.”

But that’s exactly what happened. In about a month — light speed for many school districts — Nashville formed a corps of 5,600 navigators. That’s roughly half of its entire staff, each carrying average caseloads of six to 12 students each.

For the 65 percent of navigators who are teachers, the weekly calls are on top of their normal classroom loads. The tasks involve everything from helping families avoid truancy letters to referring them to dental care. The data shows that for every 125 check-ins, navigators identified one issue they couldn’t resolve through a simple phone call. They share their concerns with counselors and social workers, who step in to get families additional help. The rate of those referrals has been constant, Randolph added, suggesting an ongoing need for the program.

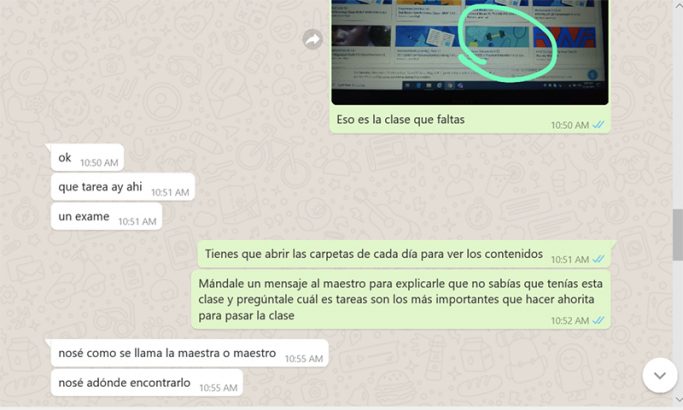

A Spanish-speaker, Gaskin is the default navigator for a lot of immigrant and refugee families, who struggle with “generational computer illiteracy” and need help with their children’s distance learning platforms. Other times, parents ask her to translate messages from their schools. “They are just utterly grateful, and they always sign off with, ‘Ok, now that I know you, can I call you about anything I need?’” she said. “Of course, I say yes.”

‘An opportunity to vent’

For parents to get that comfortable took time. Initially, many were skeptical.

“The first four to five weeks of Navigator calls were difficult, to say the least,” said Myra Taylor, executive principal of Jones Paideia Elementary Magnet School. “Calls from school usually mean your child is in trouble, something is wrong, or we need something from you.”

In designing the program, Randolph gave staff members a script. Required questions focused on problems with distance learning and participation in meal programs, for example. But there are also optional prompts, such as “Share one thing you did that you were proud of.”

For some parents, “it’s an opportunity to vent, quite honestly,” said Candace Reynolds, a secretary at Jones Paideia Elementary who serves as a navigator for 20 students. One goal of the program, she said, is to guide families through the deluge of information that’s been hitting them since school began, particularly deadlines on whether to choose in-person or remote learning.

“The last thing you want to hear is, ‘I never heard about it. I wouldn’t have done this if I had known,’” she said.

Some families only needed the navigator’s support at the beginning of the year. Once Michelle Effler got some online access codes for her seventh grader, she stopped responding to the navigator’s messages. But she appreciates the effort.

“It’s great to know that our school is reaching out to us and offering their support,” she said. “I personally prefer to be overly communicated with as opposed to the alternative.”

Some issues are a quick fix. Jennie Presson, an instructional coach at DuPont Tyler Middle School, learned that fifth grader Disha Patel ran out of paint — and didn’t like completing her art projects with colored pencils and crayons. So Presson surprised her with a paint set from Amazon.

The gesture made Disha feel special. “I’m going to try to … use the paint to make her something,” she said.

Other check-ins uncover more serious concerns. A routine call from a navigator at Jones Paideia Elementary about technology revealed that one family didn’t have any food in the house. Before the end of the day, staff members delivered them two bags of groceries.

“We may have not known about this critical need if we were not making contact weekly and building a relationship that provided a safe space for this mother to share her needs,” Taylor said.

‘What we should be doing’

Randolph and other leaders initially worried that teachers would view their Navigator caseloads as one more series of tasks to complete in an already punishing year. And they were right.

“There was some pushback and frustration from teachers regarding this ‘extra responsibility,’” Taylor said. But the district views involvement in the program as non-negotiable. “It’s what we should be doing for all students, all the time.”

Gaskin, a member of the Metro Nashville Education Association, said some teachers have been concerned about the “size of the ask.” Most teachers in the district are not members of the union, which in Tennessee has limited bargaining rights anyhow. The union did not respond to requests for comment.

The work is time consuming, Gaskin said. One phone call often leads to several more. She hasn’t spent as much time on her lesson plans as she would have normally. But she said she supports the program and was “strongly motivated” by wanting to keep students engaged.

“I decided I was going to fill this role with gusto and let the other stuff simmer,” she said. “I was afraid we would have massive dropouts and failure.”

Initially, Gaskin lacked access to grades for the students on her list. Now navigators can view students’ records, and Randolph created a dashboard that displays the families the navigators contacted, the issues discussed, and whether they made an additional referral.

Some students, however, remain difficult to reach, particularly those among the city’s large refugee population, mostly from Latin America, Burma, and Somalia. And for those, the Navigator program is not enough. “We’re at the point now where we’re knocking on doors, and it is a one-on-one conversation,” Randolph said.

Other families prefer to be left alone. Unless parents opt out, as about 3 percent of the district’s 86,000 students have, all students are part of the program. The navigators still get a few hang ups, Taylor said.

This hasn’t stopped Randolph from envisioning a post-pandemic future for the model. At the moment, the district measures success in terms of the numbers of families reached. But they want to examine whether navigator support leads to other positive outcomes, like good attendance.

Randolph would like to see navigators stick with the same group of students throughout elementary school, guiding them as they transition to the middle grades.

“This is something that will persist,” she said.

This article is one in a series spotlighting the broader consequences of families disenrolling their children, students changing schools and children going missing amid the coronavirus crisis. See all our coverage at ‘COVID’s Missing Students.’ (If you or a student you know changed schools or stopped going to class altogether because of the pandemic, tell us your story. On Twitter: #WhereAreTheKids and #IAmHere)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter