Colorado District Uses High School Apprentices to Grow Its Own More Diverse Teacher Workforce

Thalia Jones had always liked the idea of becoming an educator. But she wanted to make sure it would be the right fit.

“I needed reassurance to know that I was going to be a good teacher, like [that] this was my calling, before I’m going to school paying for it and then it’s the wrong thing,” said Jones, who is a high school senior in Denver, Colorado.

Fortuitously, during her junior year, in the middle of a computer science class that she had begun to tire of, a representative from her Cherry Creek school district came to introduce an opportunity: students could join an all-new “future educator” program to shadow local primary school teachers and work with younger kids as paraprofessionals — all while earning an income.

“I felt like it was kind of meant to be when they came into that classroom,” Jones said. “They were like, ‘Does anybody want to be a teacher?’”

Jones raised her hand.

“I’m so glad that I made that decision,” she said. “Because it led me here.”

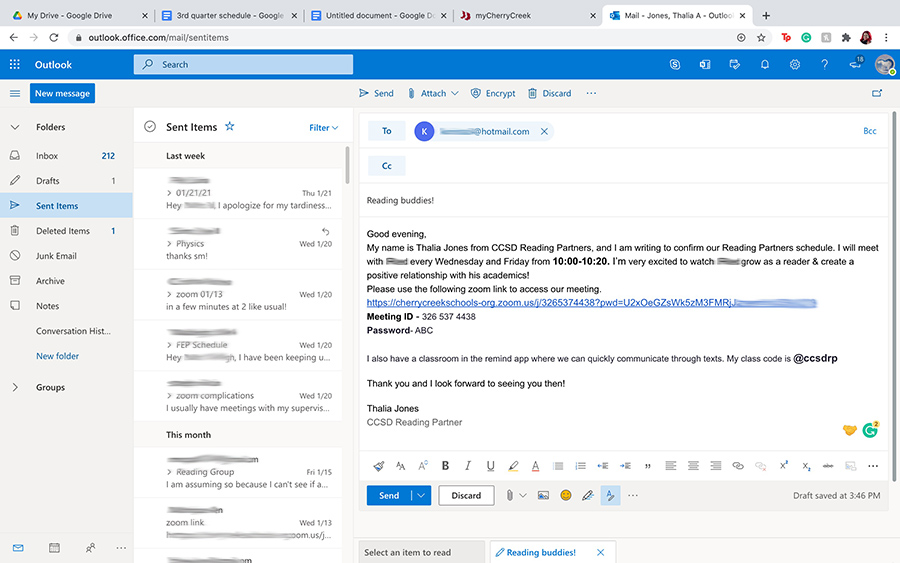

Now, five days a week for about three hours each day, Jones works with elementary students at Cherry Creek Elevation, the district’s online school option for students whose families opted out of in-person learning this year. She shadows a veteran fourth-grade teacher, holds “reading group” sessions for students who need extra help and even runs her own class two days a week. In the process, she has racked up college credits and earned admission into several in-state colleges and universities to continue her training as a teacher.

Jones is one of 26 high school juniors and seniors who participate in Cherry Creek’s future educator pathway. The program, now in its second year, has two central goals: First, as a part of a broader push to provide apprenticeship options to students in the district, it’s a way to give youth like Jones real-world work experience while still in high school.

But the program also seeks to address a problem pervasive in the 55,000-student district, and common in school systems across America: teacher forces that don’t reflect student bodies. While approximately half of students in the southeast Denver district are kids of color, 85 percent of teachers are white, slightly above the 79 percent share of educators nationally.

“We need to increase our teachers of color in the Cherry Creek school district,” Superintendent Scott Siegfried told The 74. “We know that’s good for all kids to have a diverse workforce in front of them.”

When jobs would open in the district, most applicants would be white, Siegfried said. Cherry Creek was having trouble finding educators of color.

So the district tried a novel solution: recruiting and training its own students.

“We really focused on, ‘How can we get a better representation — racial representation — of educators inside of Cherry Creek schools?’ Well, it’s to grow the ones that are here inside already,” said Assistant Superintendent Sarah Grobbel.

In its first two years of operation, 42 percent of youth apprentices working in the future educator program have been Black, Asian, Indigenous or Hispanic — still a notch below the proportion in the district’s full student body, but well above the 14 percent of Cherry Creek’s full-time work force who are employees of color.

As districts across the country grapple with how to effectively diversify their teacher forces, the Cherry Creek program appears promising and comes at a serendipitous time. Right now, Congress is considering the National Apprenticeship Act of 2021, an update to a 1937 bill passed on the heels of another economic crisis. This spring, federal lawmakers will debate strengthening career training opportunities as the pandemic continues to destabilize the postsecondary and employment plans of many young people.

‘A part of me wasn’t being represented’

As a student, Jones is all too familiar with the problem of learning from homogenous, all-white teachers. Before moving to Denver as a high school junior, she grew up in Nashville, Tennessee, where, as she put it, “All of my teachers, for the most part, were old white guys.”

Her history classes especially would tell distorted narratives, said Jones, celebrating Thomas Jefferson and visiting his plantations, for example, without critiquing him for owning or having sex with slaves, notably Sally Hemings, who bore six of Jefferson’s children. During conversations on slavery or civil rights, she would sometimes disengage as a coping mechanism.

“You don’t want to say certain things to certain people,” said Jones, who is Black. “I felt like a part of me wasn’t being represented.”

Now Jones plans to become a history teacher herself to set the record straight.

“I want people to understand the truth of American history,” she said.

Even as an apprentice, Jones knows her racial identity plays into her presence as an educator. As she sees it, “being a teacher is more about being considerate of … kids’ circumstances and how they learn and what learning is like for them at home, than just teaching the material.”

“I feel like being a Black person, I’m already kind of conscious of those things,” said Jones.

To apprentices whose life experiences may not otherwise provide that level of consciousness, learning from a diverse cohort in the future educator program has led to key growth.

“I’ve heard how some of my peers have grown up differently than me,” said apprentice Emma Tucker, who is white. “It’s something that I can really use in my future to help my students and make sure that when I’m a teacher, I’m providing them with the best learning experience, no matter what their background is.”

And to students who perhaps are used to seeing their identities underrepresented, the makeup of the cohort provides an affirming environment.

“I work side by side with a lot of people that look like me,” said future educator Aariyah Johnson. Like Jones, Johnson is also Black. “It’s really encouraging and makes me definitely want to continue [working as a teaching apprentice]. And it makes me feel welcome.”

An ‘options multiplier’

For Jones, leading a classroom has turned out to be a natural fit. She has formed strong connections with her young learners, encouraging them to try reading more challenging books, she says.

But throughout her school career, being a student wasn’t always easy. Before beginning her apprenticeship, Jones fretted over her college chances.

“I did not do so cute (well) on the ACT. My GPA is really regular,” she said. “I know that I have the passion to be an educator, but without the program, I really wouldn’t even be able to back that up.”

Now, the high school senior is sitting on acceptance letters from three colleges, and feels good about her choices. This past year, she’s been taking CU Denver courses online, and the credits will transfer to any in-state school where she opts to continue her training next fall.

According to Noel Ginsburg, founder of CareerWise Colorado, which facilitates Cherry Creek’s apprenticeship program, Jones’s case exemplifies the pathway working as it should. It’s a misconception, he says, to think apprenticeships funnel students toward careers only in the trades. Many open the door to higher education.

“You can start with an apprenticeship and end as a Ph.D,” explained Ginsburg. “It’s really an options multiplier.”

The CareerWise CEO often watches challenged students make up ground on their coursework after beginning their apprenticeships.

“They will come up to grade level faster than if they are just in the school because they can see the relevancy of, ‘This is why I’m learning. I need to know math or I have to write emails, and if my English writing skills aren’t strong enough, I won’t be successful,’” said Ginsburg.

“The applied learning helps improve their academic learning as well.”

A win-win for students and employers

Cherry Creek’s effort to train the next generation of educators through on-the-job experience in high school comes amid a larger push to scale up apprenticeship opportunities nationwide.

Congress is considering legislation that, among other smaller expenditures, would appropriate $3 billion in grants over a five-year period to intermediary organizations like CareerWise seeking to connect employers with apprentices. The bill awaits a Senate vote after passing through the House in early February with bipartisan support. If approved, it will likely find a friend in President Biden, who has expressed interest in expanding apprenticeship opportunities.

Experts agree that such programs can be a win-win for youth and employers. International examples like Switzerland, where about 70 percent of high school students participate in apprenticeships, says Taylor White, senior policy advisor at New America, demonstrate the business-side financial incentives.

“There’s a positive return on investment in apprenticeship,” she said. Each Swiss apprentice, over a three-year span, nets their company an average of $9,000, even while earning a salary of their own.

That three-year duration is key, says Brookings Institution economic geographer Annelies Goger, because it gives companies ample time to invest in quality job training for their apprentices. “The longer that you make the period, the more the employer is able to recoup that investment,” she explained.

At CareerWise Colorado, which emphasizes the longer-term model, Ginsburg can rattle off example after example of students who won big for their companies. One student working for Pinnacol Assurance, with no prior computer science experience, learned to write code and was able to automate processes that used to take thousands of labor-hours to carry out, Ginsburg says. At his own company, Intertech Plastics, a student apprentice designed automation cells that allowed them to move manufacturing back from China to Colorado.

CareerWise had 217 active apprentices as of mid-February, and in an annual survey, 90 percent of graduating apprentices reported that they gained useful professional connections. Even when the pandemic hit and scores of other companies cut such programs short, 68 percent of CareerWise apprentices retained their position, which Ginsburg says reflects their value to the companies where they are placed.

CareerWise Colorado was launched after a trip abroad to learn about the Swiss system for youth apprenticeship.

The professional domains compatible with apprenticeship opportunities are set to grow, according to a 2017 study from Harvard. Given the demands of the 21st century labor market, it found that the number of job categories typically filled by apprentices could nearly triple — from 27 to 74.

“There are so many occupations that really lend themselves to on-the-job learning coupled with classroom instruction,” said Lul Tesfai, New America senior policy advisor.

A promising program

If the example of Cherry Creek is any indication, teaching may well be one of those fields. After starting with an inaugural 12-student cohort in 2019, the program currently has 26 future educators and is poised to grow to upwards of 50 participants next year based on applications.

“These are paraprofessionals that we would hire anyway,” explained Assistant Superintendent Grobbel, so even though the apprentices earn $12.68 an hour, the budget balances out.

The administrator has begun to receive calls from across the country for tips on launching similar apprenticeship opportunities, she reports. And last year, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis supported legislation to replicate the Cherry Creek program, his press secretary Conor Cahill told The 74.

“These are the types of strong pathways that help to connect students to meaningful careers, while helping to address persistent teacher shortages in our state,” Cahill said.

The trick to the district’s success, says Grobbel, is a shift in mindset.

“As adults, in our minds, we limit what we think students are capable of doing,” she said. “Normally, when you talk about a high school student that’s working in a school, you give them recess duty, or … you give them lunch duty. But these students really are hired for instruction and so that makes a huge difference.”

Jones, for one, exemplifies just how effective apprentices can be at their jobs, even while still in high school. Despite teaching in a year marked by the frustration of remote instruction, she has instilled an enthusiasm for learning in her students. “They ask their parents about what we can read the next time that we’re together,” Jones reports.

Halfway through sessions, she pauses to let students guess what will happen next in their book. “If their predictions are right, I can see them … blushing,” said Jones.

As for Cherry Creek, a district on a mission to recruit high-quality teachers of color by growing their own in-house talent, it seems that their plan may be working.

Jones, Johnson, and Tucker all say they would strongly consider one day returning to the district to work. On top of that, it seems that the program has trained some lifelong educators.

“This is something that I can see myself doing for a long time and being happy,” Jones said.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to CareerWise Colorado, New America, the Brookings Institute and The 74. The Carnegie Corporation of New York provides financial support to New America, the Brookings Institute and The 74. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provides financial support to New America and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter