Dallas ISD’s Opt-Out Policy Dramatically Boosts Diversity in Its Honors Classes

A 2019 policy change increased the number of Hispanic, Black & English learner children — the majority of Dallas students — without decreasing scores.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It was a barrier that kept many Dallas Independent School District students from taking courses that reflected their potential: Those who wanted to join honors classes in the sixth, seventh and eighth grade had to opt-in themselves or had to earn a recommendation — typically from a teacher or parent.

Many capable Hispanic, Black and English learner students did not elect to join these classes on their own or were passed over by their instructors. And their parents were often unaware they could make the request.

Dallas ISD, which serves some 142,000 children, took note of the disparity and in 2017 formed a racial equity advisory council — some of whose members had children in the district — with the goal of improving opportunity for all.

It decided to move from an opt-in model to an opt-out policy in the 2019-20 school year. Since then, all students who score well on state exams are now automatically enrolled in advanced mathematics, reading, science and social studies — or some combination of the four. Under the current model, students cannot opt out without written parent permission. The move has dramatically increased participation among traditionally marginalized children.

The initiative is particularly consequential in mathematics. It places far more students on track to take eighth-grade algebra, a prerequisite for more advanced coursework in high school. Prior to the shift, only 20% of Dallas ISD 8th graders were enrolled in Algebra I compared to 60% today.

“We talked about some cold hard facts and part of that was to … increase enrollment in the good stuff and ensure students are going to be successful once we get them in there,” said Shannon Trejo, Dallas ISD’s chief academic officer. “Advanced coursework in high school is a pipeline: You have to get in in middle school. The question was, ‘How do we ensure students who are prepared are enrolling?’”

And the policy has not led to a decrease in student scores as some speculated: Last year’s 8th-grade Algebra I students had similar pass rates as those in years prior, the district said, with 95% of Hispanic students passing the test and 76% meeting grade-level proficiency; 91% of Black students passing and 65% meeting grade level and 95% of English learner students passing the state exam and 74% meeting grade level.

Drexell Owusu, chief impact officer at The Dallas Foundation, which connects donors with charitable organizations among other endeavors, said he appreciates the district’s decision to raise the bar for students who’ve shown they are capable of more challenging work.

“As a parent to three Dallas ISD students, I hold my own children to this standard, knowing that the challenge of advanced coursework is how they will reach higher heights as learners and people,” said Owusu, a member of the district’s advisory council. “As a business and community advocate, I’m thrilled with the increase in success rates for honors courses knowing that this will lead to great jobs and increased living-wage attainment for these students in the future.”

Dallas’s decision to open up its honors classes comes as educators and advocates across the country are reckoning with racial inequities in advanced courses and questioning whether current curricula serve today’s students. Some are urging decision makers to include access at every turn of a child’s academic career and to consider more modern and relevant coursework.

This is particularly true of calculus, long considered a benchmark of high school success and often perceived as a prerequisite of college admissions — at least for wealthier students who have access to the course, which can be hard to find in Black, Hispanic and impoverished communities.

Like many school districts across the country, Dallas saw its math scores falter in recent years, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, often called the “Nation’s Report Card.” Eighth-grade math scores dropped by eight points nationally since the test was last administered in 2019, while fourth-grade scores dropped by five points — the largest decreases ever recorded.

The results were less alarming for Hispanic eighth graders in Dallas, who saw their scores fall from 265 to 261 and Black students in that grade who saw their marks dip from 252 to 249. The city’s fourth-grade math scores were about as dire, with Hispanic students in that grade seeing a six-point drop, from from 236 to 230, while Black students slid from 222 down to 218.

Hispanics make up 71% of Dallas’s student body, Black students account for 20% and English language learners, who the district refers to as emergent bilinguals, make up 49%, according to Dallas ISD’s most recent data. White students account for 5.5% of total enrollment.

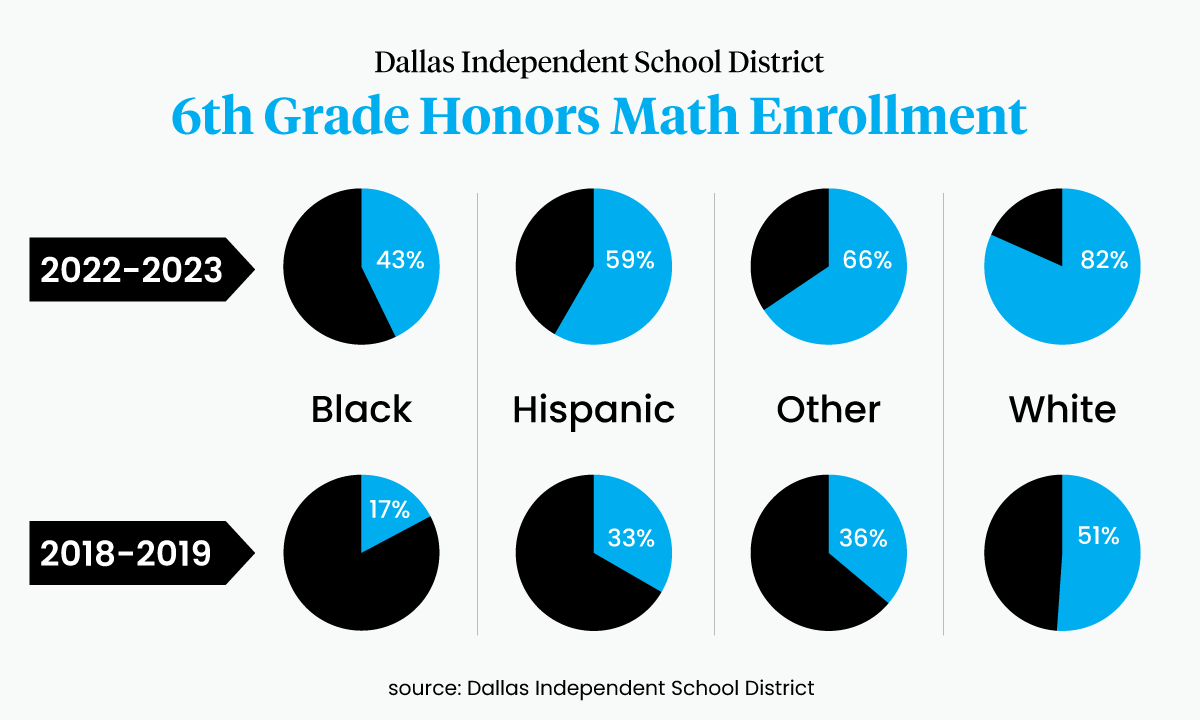

Students of color had been dramatically underrepresented in the district’s advanced programming. Just 33% of Hispanic sixth graders, 17% of Black sixth graders and 31% of English learners in that grade were enrolled in 6th-grade honors math classes in the 2018-19 school year. Conversely, 51% of white sixth graders took advanced math that year.

By the 2022-23 school year, 59% of Hispanic sixth graders, 43% of Black sixth graders and 59% of that grade’s English learners were enrolled in 6th-grade honors math classes. The percentage of white sixth graders in advanced math also grew substantially, to 82%.

In past years, Dallas ISD school board Trustee Ben Mackey said some students weren’t selected for such programs because teachers believed they misbehaved in class.

“Maybe that kid was acting up because they were not challenged,” he said. “Within two years of this policy, 94% of eligible students are taking these classes. It makes such a drastic difference in terms of whether the student will be college ready and career ready. We need to give every single person a chance to be successful in life, so when they leave us, they are not three steps behind.”

Juany Valdespino-Gaytan, the district’s executive director of engagement services, said the new model helps capture talented students who might not have known about the honors path.

“The whole premise is that we are really trying to increase access to all students,” she said. “The policy change was our first effort toward that goal, making these courses available to any student and automatically requiring them to opt out. It puts students in a space where they are advocated for based on their performance.”

Trejo, the district’s chief academic officer, said Dallas ISD is tracking outcomes year over year, with a focus on whether students continue on an advanced pathway in high school.

“I want our kids to graduate and be able to choose among different colleges and among different careers because they have been so well prepared in mathematics that people want them,” Trejo said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter