How Many Start Teacher Training — & How Many Finish? The Numbers Are Disturbing

Patrick: The future of the teaching workforce may depend on where you live. A state-by-state analysis may shed important light.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Last year’s back-to-school headlines were dominated by concerns about teacher shortages. It doesn’t take a crystal ball to predict that, without meaningful policy changes, staffing challenges will continue to undermine U.S. education and shortchange the country’s students. A growing number of states are seeing increased teacher turnover, and a new national scan of 2020-22 state-level data by the Learning Policy Institute estimates more than 300,000 teaching positions in the United States were either unfilled or held by people who were not fully qualified — meaning they lacked credentials, held an emergency or temporary credential, were teaching while they completed their credential or were working in a subject or grade not covered by their current credential.

As pressing as it is to get qualified teachers in classrooms immediately to address shortages, effective policy must also focus on recruiting a well-prepared and diverse pool of candidates, along with retaining effective educators.

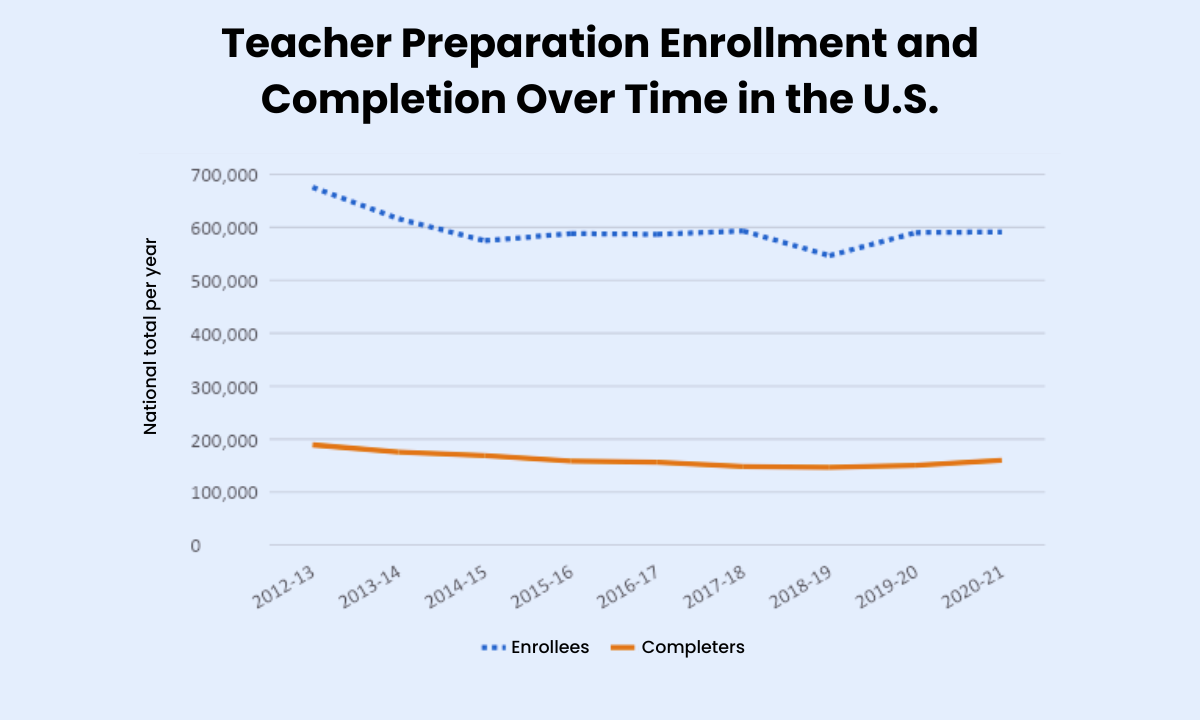

Unfortunately, interest in teaching among high school and college students is at the lowest level it’s been in decades. Nationally, enrollment in preparation programs never quite rebounded after the Great Recession. National data, collected by the U.S. Department of Education under Title II of the Higher Education Act since 1999-2000, show that enrollment dropped by about 100,000 candidates between 2012-13 and 2014-15 — a 15% decline. Forty states experienced declines in enrollment during this two-year period. From 2015-16 to 2020-21, total enrollment has remained fairly steady at just under 600,000 nationally, with a dip of about 45,000 candidates in 2018-19 that quickly rebounded in the following year.

But enrollment figures don’t tell the whole story, and, importantly, the number of people completing teacher preparation programs nationwide declined by 20% — about 40,000 — between 2012-13 and 2018-19, with modest increases of about 15,000 between 2018-19 and 2020-21.

While the national picture on enrollment and completion is still concerning, national trends hide considerable differences across states. Our recently published analysis on the state of the

teacher workforce includes recent data on candidate enrollment and completion in teacher preparation programs by state. The Title II data from the most recent five years (2016-17 through 2020-21) show that 27 states have seen ongoing enrollment declines of 5% or more, seven states had relatively flat enrollment numbers and 17 states plus the District of Columbia saw increases of 5% or more.

To understand this variation in enrollments and completions across states and the range of policies in place, it helps to look at some specific examples; these differences among states may shed important light on policy approaches that may expand the teacher pipeline.

Washington state posted 17% increases in enrollment and 22% increases in completion over the past five years. Washington has invested in numerous statewide policies and programs to address teacher recruitment and retention, such as increasing scholarships for candidates preparing to teach in high-need subject or geographic areas and investing in grow-your-own programs.

California saw a 2% increase in enrollment and a 27% increase in completion rates over the past five years. The rise in the supply of fully prepared new entrants (and associated decline in hires with emergency-style permits) has coincided with substantial state investments to address teacher shortages, including $170 million in a grow-your-own program to support paraprofessionals and other school staff to become teachers, $515 million for scholarships for teachers who commit to teach in high-need schools and more than $600 million for teacher residency programs. These efforts are contributing to a supply of new teachers that is growing in both size and diversity: More than half of California’s newly prepared teachers are people of color.

By contrast, Louisiana experienced a 25% decline in enrollment and a 23% drop in completion over the past five years, prompting the legislature in 2021 to create a statewide task force charged with studying the issue and providing a road map for recovery.

In Texas, enrollments have increased by 22% over the past five years, driven in large part by for-profit alternative preparation programs. Importantly, this has not led to rises in completion, which decreased by 9% — leaving the state with a declining number of fully prepared new teachers. Recognizing this, in 2021, the state began investing in high-retention pathways into teaching through the Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports residency program and grow-your-own initiatives. These research-based approaches align with growing evidence showing that effective preparation, especially well-supported clinical practice, is critical to ensure that beginning teachers are instructionally effective and remain in the classroom.

The experience in Texas is not unique. Multiple studies across multiple states have found that candidates from traditional student-teaching programs and residencies are more likely to complete their training and stay in the profession than those from alternative routes that do not provide full preparation before new teachers enter the classroom.

The wide-ranging differences in state rates of preparation program enrollment and completion also make it clear that addressing shortages is not a futile ambition. Not only is it possible, but it is happening in places with policies that foster long-term investments in affordable and effective pathways. And, with an ongoing focus on supporting and retaining the existing teacher workforce, the nation may finally be on the path to ending shortages for good.

Disclosure: Walton Family Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Nellie Mae Education Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provide financial support to the Learning Policy Institute and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter